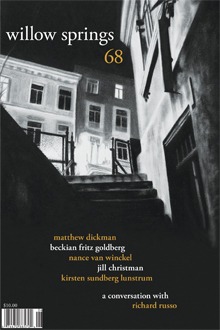

Found in Willow Springs 68

April 17, 2010

Sam Edmonds, Laura Ender, Brendan Lynaugh

A CONVERSATION WITH RICHARD RUSSO

Photo Credit: Authors Guild

Richard Russo was born and raised in the “Glove Cities,” Johnstown and Gloversville, New York, which would become the backdrop for many of his novels. In a 2007 interview with NPR, he said, “I’ve always had the distinct feeling that there was a ghost version of myself still living back in that place that’s still so real in my imagination and that I’ve been telling fibs about all this time.” In “High and Dry,” an essay featured in the summer 2010 issue of Granta, Russo revisits his hometown, grappling with the unpleasant history of Gloversville’s leather tanning industry.

Russo is the author of seven novels, including the Pulitzer Prize- winning Empire Falls, Bridge of Sighs, and most recently, That Old Cape Magic, as well as a collection of short stories entitled The Whore’s Child. His work has appeared in a variety of periodicals, including The New Yorker, Harper’s, and Esquire. He’s written and co-written screenplays for movies such as the 1998 film Twilight and 2005’s The Ice Harvest.

Russo’s work has been widely lauded for its humor, its sharp storytelling, and its keen portrayal of the world it inhabits. The New York Times called Bridge of Sighs “an improbably neighborly and nonchalant version of the great American novel.” In a review of That Old Cape Magic in the Washington Post, Ron Charles said, “American white guys may have no better ally in the world of fiction than Richard Russo.”

We met with Mr. Russo at Spokane’s Davenport Hotel, after attending a panel discussion in which he and several other screenwriters talked about the intricacies of adapting novels into films. We discussed the ups and downs of writing partnerships, damaged characters, humor and suffering, Russo’s doctoral study despair, and how he discovered that he was going to become a fiction writer.

Sam Edmonds

In a 2006 interview, you said that you initially wrote to avoid working construction in college, and then you wrote to avoid doing scholarly research. Did this type of avoidance get you where you are today?

Richard Russo

I did what a lot of people who love literature do. You become an English major, and you think what a great deal this is. You spend your time reading great books, you write about them a little bit, it enriches your life, and if you become a teacher, you can make a decent enough living out of it. So you do a BA, and then you do an MA, and the MA is even more fun, because you get to concentrate. If you liked Huckleberry Finn, for example, then chances are pretty good that you’re going to be able to take courses where you get to read Pudd’nhead Wilson and all the other good Twain stuff; you get to go deeper, and the more of it you read, the better rounded you become as a human being and certainly as a reader and teacher. But to have the kind of career that a lot of people in that circumstance want—why not do the PhD? And then you can become, instead of a high school teacher, a professor. There’s a kind of allure to becoming a professor, but when you get into the PhD program, you realize that you’re not really reading books anymore; you’re reading books about books. You’re reading scholarship. And you keep going, because you’ve started, and you don’t want to stop once you’ve started something. But every year in the PhD program I became more unhappy. I had started down a road that was only likely to get worse. I was looking at my professors at the University of Arizona, the people in literature, and seeing how difficult it was for them to find ever more and more obscure things to write about. You couldn’t just teach the books you loved, because you would never get tenure that way, and so I found myself starting down this road toward scholarship regarding second- and third-ranked writers and some of their most obscure books. I found that I would have to buy that franchise. I would be serving that food, and you’ve got to defend it against other franchises, or other people who want into your franchise. So you become the Twain scholar or whatever. By the time I’d finished my course work and was starting to write my dissertation, I was in a pit of despair. I realized I’d made a terrible mistake that was going to affect and infect the rest of my life. I could see absolutely no way out of it, until I discovered creative writing. I discovered that, in doing all of that reading, I was studying to be a writer. Creative writing gave me another avenue, and it saved my life.

Brendan Lynaugh

So studying literature, as opposed to creative writing, helped you become a writer?

Russo

Yes, especially the kind of reading I was doing. A lot of my colleagues, who were in the MFA program in fiction writing, were reading contemporary stuff. I don’t want to call it a literary dead end, but it certainly wasn’t mainstream. They were reading William Gaddis, Stanley Elkin, Vonnegut, William Gass, John Hawkes, all the biggest names in metafictional, experimental writing, and they were all weaned on it. That would not have been good for me, because as great as those writers were at what they did, I was, without knowing it, going to be writing 20th century or 19th century novels. That’s the kind of writer I was going to be. I wasn’t interested in metafictional games, and it didn’t matter to me how great that stuff was, whereas, when I realized that I was going to have to start reading contemporaries who were doing what I wanted to do, I discovered Richard Yates and John Cheever, and all those people who are much more traditional and had a sensibility closer to my own. I was the kind of writer who was informed by Dickens, the Brontës, and Twain, all of whom were clearly more important in terms of the writer I ultimately became than if I’d been taking contemporary fiction courses in writers who, despite their brilliance, didn’t have much to say to me.

Lynaugh

You’ve done a lot of screenwriting in addition to novels and short stories. Has screenwriting enriched your fiction?

Russo

When I first started writing screenplays, I had some writer friends who said, “Oh, do you really dare to do that? Aren’t you afraid?” They said they would be afraid of all sorts of things—that I would be corrupted by film, corrupted by the Hollywood lifestyle. When I wrote my first script, a couple of friends said, “Are you going to move to LA?” As soon as you mention that kind of work, there’s an aura about the whole thing—“Oh, Russo’s sold out,” as if I’d give up novel writing, move to LA, drive a Porsche, and do nothing but take meetings. Needless to say, none of that happened.

The other thing people worry about, when they worry about novelists working in Hollywood, is that the novels you write after writing screenplays will become more like screenplays and less like novels, that they’ll become dialogue-heavy, take place in time present, that the amount of fictional time that will take place in order for the story to unfold will get smaller, that everything will shrink. They say, “Aren’t you afraid you’re going to become a different kind of writer?” And strangely enough, writing screenplays plays right into my strengths, because most screenplays are about dialogue, which comes easiest for me. The other thing about screenplays—they’re action heavy. You put characters in motion and let them talk and behave in ways that reveal their inner life, and those are the two things that, for me, are easiest to do.

What happens when I’ve been working on a screenplay for a while, though, especially if I do a couple of screenplays, is that it almost feels like I’m cheating. Because I’m not required to do the things that are, for me, the most difficult. I’ve always thought that I have a better ear than eye, and when I’m writing badly, it’s like I’m taking dictation. Somebody says something, somebody responds, somebody says something, somebody responds. When I’m writing badly, I’m often writing very quickly, and what’s happening is that my ear’s taking dictation, and my eye’s forgetting to see the world out there. I have to remind myself, Slow down, slow down, because if you’re missing things with your eye while your ear is having a real good time, and if you’re just moving along at that great pace, you’re going to miss important props in a story, important objects. After I’ve written a couple screenplays, when I get back to writing novels, I feel like I’ve been working with a hammer and a wrench, maybe a socket wrench, and when I start on a novel again, it’s like I take out my old tool box. I’ve only been using a couple of tools, and then I flip it up and look at all those things in there that you use when you write

a novel; it’s good to be able to use all those tools again.

I started writing screenplays right after Nobody’s Fool came out. I worked with Robert Benton on the film version while I was writing Straight Man. The two novels that came after that were Empire Falls and Bridge of Sighs, both of which were bigger, more expansive, more interior. I never spent as much time as I did in Bridge of Sighs describing the physical world; I just luxuriated in all the physical objects, from the trunk that Lucy gets stuck in, to the items on the shelf of that store, and how they were placed, and how the store was going to be run. All of that stuff became enormously important, because I’m not a particularly interior writer. I don’t spend an enormous amount of time in my character’s heads. I like to know who they are as a result of what they say and what they do. And yet, in those two books, I probably spent more time in my characters’ heads than I had in any of my other books. I trace that back to screenwriting, because I had those things denied. So when I came back to novel writing, I was able to embrace them in a way that I hadn’t before, and make them part of my repertoire.

Lynaugh

How is the process of writing a screenplay different from writing a novel?

Russo

Screenplay writing is much more collaborative, although I enjoy collaborating with the director much more than collaborating with other writers. There are two times that I’ve worked with another writer on a screenplay, once with a Colby colleague of mine at the time, Jim Boyland, who was interested in learning the form, and had an idea. So I said, “Well, let’s sit down and we’ll write the first act of a screenplay.” We wrote a couple drafts and sent it out to a few people, and there wasn’t an awful lot of enthusiasm about it. Some liked it, some didn’t, and some thought it would be difficult to get made. But at any rate, Jim was having a wonderful time, and that’s the kind of person he is, very collaborative, and he enjoyed the process. Plus, he was learning.

So I worked with him on that, and then I collaborated with Robert Benton on Nobody’s Fool, but it wasn’t so much a collaboration. He was unable to work on it, because it was snowing and he was shooting every day and he was getting further and further behind, so he would send me a set of instructions, and I would rewrite a scene. After that, we wrote a script together called Twilight. I’d send him twenty pages worth of scenes, and he’d write back and revise what I’d written, and then I’d go back and revise what he’d written, and then for a while he would take over the story and write for twenty pages or so and send me what he’d written, and I would busily change everything he’d done and send it back to him. When we got about a hundred pages into this detective movie, neither of us knew who had committed the murder, and we were twenty pages from the end of the script. So we went backward and just decided, All right, here’s the guy who committed the murder. All right, so why?

And then we worked backward and rewrote the screenplay the same way. Even as I tell that story, it’s astonishing to me that the movie could possibly have been made working in that lunatic way, and I think that Benton is a genuine collaborator. He loves to collaborate with another writer. He loves to collaborate with the actors. He even enjoys talking with producers at the beginning stages of things. How are we going to cast this, where are we going to shoot it? For Benton, making a movie is like inventing a family who you’re going to live with for a long time; he loves every aspect of it.

I had been a novelist for so long that the actual rhythm of writing twenty pages and sending it off to him and waiting for a couple of weeks for him to write back drove me crazy. To be honest, I also didn’t want to share. I was having a good time. It wasn’t that I didn’t want his opinion, but I would have rather written the whole thing start to finish and had him revise the whole thing start to finish. It was like reducing a three year film school program into five months, because he’s such a brilliant writer and director. But after learning what I learned, I thought to myself, I don’t think I want to collaborate in quite that way again.

Laura Ender

Is it difficult for you when actors become part of the collaboration?

Do you trust them?

Russo

It depends on the actor. Strangely enough, sometimes the actors with smaller roles are more problematic. One of the reasons I love to stay away from the set and rehearsals is that the actors, especially good actors in smaller roles, always lobby for more lines. They wanted to do the movie, but they get into the movie, and then if the writer is on set or there in rehearsals, they’re always saying, “You know, I really love my character, but I feel like I need just a few more lines….” They’re always working behind the director’s back. The director doesn’t want to hear any of that. If the script is being rewritten at the time, it’s to the director’s specifications, not the actors’.

Some actors will want to subtract from another character’s lines. And other actors are curious—Paul Newman’s a perfect example of this. When I was on set for Nobody’s Fool, Paul was the soul of generosity, but he was also the soul of curiosity. When I went to the set the first time, he took me aside. He didn’t want the director there, didn’t want anybody there, and he started rifling questions at me: “When Sully’s alone in his truck, what kind of music does he listen to?” He had a whole list of questions, and it was so deeply embarrassing and humiliating, because I didn’t really have any answers for him. I had no idea what kind of music Sully would listen to. Everything I knew about that guy was in the book, and it wasn’t like there were outtakes that I could sweep up from the floor. But he was voraciously looking for anything that would give him more of a handle on who this character was. When I met him, he was already limping, and I almost asked him if he’d hurt himself, until I realized he was in my character, Sully, who’d broken his knee. Paul limped during that entire shoot, on and off camera. He was always looking for something to anchor his character to—he wasn’t looking for dialogue. It was nothing that was ever going to be on the screen, except in a close-up on his face.

We had a pivotal scene, where Sully and his son are sitting in a truck, and his son has asked him, basically, why he left him and his mother. Sully’s explanation to his son in the script was a page and a half, Sully talking about the kind of man his father was, the kind of woman his mother was, how much his father drank, how difficult it was for his mother, who tried to step between his father and him. It was a writer’s explanation of a character that Paul felt very uncomfortable, in character, giving to his son. So he kept asking us to cut. And I would cut and cut, and it was still too much. We finally got it down to a third of the size it was. It became a wonderful scene. In my script, I had written about one particular night where Sully’s father had just beaten the crap out of his mother, and Sully found her on the floor and she was bleeding. Paul took all of that out and I think kept just one or two lines. He says “Your grandfather… your grandfather…” And he pauses, and just looks off, and then says something like, “And of course your grandmother, she was just a little bit of a woman. He could make her fly.” That was it. “He could make her fly.” All the rest of it, he cut out. Everything that man had ever done to that woman was written on his face. We didn’t need any details. He just had to know what had happened to him as a young man, and all the explanation in the world wasn’t going to get him there, wasn’t going to get the movie there. He just needed a little suggestion and a metaphor, and then let all the viewers see his face and see that woman, as the result of a punch, fly across the room.

Lynaugh

You brought up Sully’s problem with his knee. A lot of your protagonists seem to have disabilities—in Straight Man, Hank has trouble peeing from the onset, and in That Old Cape Magic, the protagonist hears voices. How purposefully do you make the choice to limit or disable your characters, and how do these disabilities help the novel?

Russo

Damage plays a role, and not just with the main characters. Maybe it has something to do with my sense that that’s just human nature. We all get damaged in some way or other, and if you can make that damage seem real, we relate to it in ways that run below the surface.

In the The Risk Pool, there’s a scene that’s as graphically violent as anything I’ve ever written, a scene in which father and son have gone fishing, way back up the river, and Sam Hall, who can’t admit to his son that he has no idea how to fish, he goes up around the bend and immediately has a nest of monofilament on his line. He can’t cast anymore because it’s tangled. The first thing he does when he’s trying to untangle the line is snag his own thumb with a barbed hook, and he spends the rest of his time trying to get the fish hook out of his thumb, while his son and the other guy are fishing. Sam succeeds only in driving it deeper into his thumb as he’s trying to maneuver it out. At the end of the scene, his son, who’s ten years old, and his best friend, Wussy, come walking back up the stream, and here’s Sam sitting on the rock, still connected to his rod, and Wussy just takes one look at him, shakes his head, comes over, and says, “I need my rod back now,” and he bites off the monofilament, like Sam hasn’t figured out that that’s the obvious thing to do, because he doesn’t have any pliers. He bites off the line, takes his rod and reel back, and Sam has to follow. So all of this takes place over a short period of time, but as they walk out of the woods and get back to the car, Sam, by this point, is enraged. He wanted to take his son fishing and everything has gone wrong. As he’s driving down the road, the monofilament line, which is still hanging out of his thumb, is dancing in the breeze, and at one point they have to pull over. That’s when the car breaks down. Sam’s trying to do something with the length of monofilament still dangling, and he just can’t take it anymore. He wraps it around his finger, pulls, and a chunk of his thumb comes out. I remember the first time I read that to an audience. Everybody in the place went “Gasp!” and it taught me a lesson. We’re living in a world in which we’re seeing people blown apart, where violence gets amplified to these epic, often melodramatic proportions. But if you can get somebody to feel a small pain that they have felt, that doesn’t feel small at the time, and get them to relive that, the rewards are astonishing. I even disable dogs. In Nobody’s Fool, I give a dog a stroke. In Straight Man, Hank’s trying to pass a stone. The moments of pain come in small packages, but they can be enormously, dramatically rewarding. We’ve all had the sliver that works its way under the skin and then comes out later, and the way we worry about it.

Ender

That thumb in The Risk Pool gets injured over and over. Is the thumb symbolic? How does the character’s pain work within the novel?

Russo

Every now and then when you’re writing a book you realize you’ve done something, and it works, and you think, All right, how can I use this again? I’ve always believed, insofar as it’s possible, in what I call the rule of threes. When something really works, it’s good to use it three times. The first time it just happens, the second time it seems to pivot a little bit, and the third time brings it home. It becomes something other than the thing. The first time it’s just a thumb, Sam’s thumb and Sam’s pain. The second time, as I recall, it’s the kid trying to understand about pain, saying, How can you do that, doesn’t it hurt? And Sam trying to explain to him, that’s not the point. It’s learning to deal with it. I think when you stumble on something in the real world, you try to use it two or three times, just to see how much you can get out of it and how you can transform it from something that’s literal into something that might be symbolic, or carry a little bit more weight than its literal weight.

Ender

All your books are funny. When you go into a book, do you think, I’m going to make this funny, or does it just happen?

Russo

I think my least funny book is almost certainly Bridge of Sighs, and I don’t think I went into that thinking it was going to be less funny than my other books. If I thought it was going to be less funny, I’m not sure I would have written it, because I’m basically a comic writer. The material itself has to dictate how many laughs there are going to be. Bridge of Sighs is a book about despair, at least on some level. Lucy Lynch starts that book locked in a trunk, and lives the rest of his life kind of locked in the trunk of Thomaston, and has done a terrible thing, really, as regards his wife. He has been throwing away the letters that Bobby has been sending them, and pretending that they are going to Venice, when he knows perfectly well that they’re not. When he almost makes it across that Bridge of Sighs when he goes into his wife’s painting and he’s trying to make it all the way across the bridge into the darkness, that’s as dark a place as I’ve ever been in a book. His suffering is so intense there. If I could have seen anything humorous in that, I’m not above making a joke, as you know.

I think the best humor is related in some ways to suffering. Most of the time, if you think about them in adjacent rooms, the door adjoining suffering and humor is very often wide open, but as we get closer and closer to suffering, the doorway adjoining the rooms gets smaller and smaller, because you just can’t stand it otherwise. Or you just seem to be making bad jokes, or cruel jokes, at somebody’s expense. So it has something to do with distance, too.

Straight Man was the easiest of my books to write and the funniest. Part of the reason it was the funniest was that it was the easiest. There’s Hank suffering and trying to pass that stone, and there’s also a kind of suffering of middle age, he may be losing his wife, there’s something going on with his daughter. It’s not like there’s nothing at stake, but those stories of academic absurdity I had been storing for years—it had been almost ten years since I walked around at Penn State Altoona. I walked around a pond with the dean. Classes were to start in three or four days. He still didn’t have his budget, and he couldn’t hire his adjunct teachers. And this real-life guy said to me, “Same every year. What am I gonna do, kill a duck a day until they give me my budget?” And of course he meant it figuratively, but ten years later I figured what to do with that, and as soon as I get to make it literal, as you often do with things, you sometimes have a pretty good joke. And then, suddenly, all of the absurdity of my life as an academic gushed out. But by that time, I was out of a couple of horrible jobs that I’d had and into a good one, and I had distance on it, and I could do it without one-upsmanship; I wasn’t writing that book out of revenge. I didn’t want to do any “gotcha,” or get even with any academics. I could do it from, I hoped, a good spirit. Distance gives you the ability to do that, I think. But it’s the material itself that tells you in terms of tone just how funny it’s likely to be.

Lynaugh

When you say it all came gushing out, does that also refer to plot?

Was it easy to map the book out?

Russo

Part of a fiction writer’s job is to make it look like he knew what he was doing right from the start. When you read a novel like Straight Man, and you think, Boy, how did this get orchestrated this way? part of what you’re thinking is, How did this writer keep all of that in his mind and know exactly the time to reveal this and withhold that, and when do we bring in the woodwinds? But what happens is that you just do it, and you make all kinds of mistakes, and you don’t have to do it right the first time. It’s not like a stand-up comedian who has to go in front of an audience and get the joke right in the first telling. Really you have years. It took me five years to make it look like all the ducks were lined up facing the same direction, like I knew what I was doing from the start, whereas often what was happening was I would look at it and I’d say, “All right, we’ve gone too long here; we haven’t seen Tony Camilia in a while, and Tony is always good for a laugh.” I had him in another scene fifty pages later, but thought, Let’s move him down here, because he’ll break up this scene. We’ve seen these two characters too often, or I need to separate this peeing scene from that peeing scene. So that might have been in draft six, that I saw that this works better over here, and that over there, and you get things to line up, and then hopefully, at the very end it looks like you knew what you were doing from the start.

Ender

Did you do that kind of juggling with any of your other books?

Russo

Every single one. Straight Man was the easiest to write and Bridge of Sighs was the most difficult, partly because it was so dark, but I’d also made a terrible mistake right at the start. I’d told Lucy’s story straight through. It began with Lucy about to become sixty, planning his trip with his wife, Sarah, to Venice, and then telling the story of his life, and it was interrupted by all these flashbacks into his youth with his best friend, Bobby. I got to a point, about 250 pages into it, where I just couldn’t seem to force his story any further, and I felt trapped inside Lucy’s voice, because he’s not a reliable narrator. He doesn’t know the truth of the story he’s telling. I thought at that point that it would be kind of interesting to have Bobby’s take on all of this, so I started in, and I introduced Noonan. On page 251 Noonan is in Venice, waiting for his agent to come along. They’re going to talk about his upcoming show in New York, and whether he’s going to go to New York, and how long he’ll have to stay there, and he has not been feeling well, so he’ll go to the clinic. I set up various meetings with his agent, and I thought, All right, so he’ll have to go to New York or not go to New York. That’ll be the conclusion, but then we’ll go back and revisit many of those scenes that we saw through Lucy. Bobby’s going to see them differently, and then we’ll understand Lucy’s narrative. I wrote Noonan’s section start to finish, so now I’m up to 500 and some pages, and they’re both in love with the same woman. Well, how fair is it to have them both in love with the same woman—who would see things differently than both of them? You have to give her a say. So all right, now Sarah gets the third part, and so page 551 begins Sarah’s narrative. And now we’ve revisited some of these things three times.

I got up to about page 700, and I seemed to have three different novels. I thought I was suddenly in Lawrence Durell territory, where I was writing a trilogy or something, and I sent the whole thing off to my agent. I said, “I think I might be working on a trilogy, but if so, I don’t have an ending to any of them. I have three novels with no ending. Am I crazy?” I went to New York shortly after that, and we had a little walk around the park, as we often do, and he said “No. This is one book, but you can’t structure it this way. You have to go back and forth between all three narrators. You can’t finish one story before going on to another. You have go back and forth between past and present, and you’re going to have to withhold certain information that was revealed too soon, because it’s going to mess things up, and basically what you have to do is a juggling act, going back and forth, past and present, narrator to narrator.” I spent about an hour on our walk that day explaining to him why that could not be done, and by the time I finished it, of course I realized it could be done. By explaining to him how it couldn’t be, it got me thinking how it could be, and then I went and finished the book. Everything about that book ended up in a different place, almost, than where it was originally. I will always think of Nat as saving that novel, because I really was at a loss. I was completely up a stump. I didn’t know what happened next or how to go about it.

Lynaugh

It seems like in the past there was more of a working relationship between writers and editors, going back and forth, and now maybe that’s been replaced by agents.

Russo

I think it’s true—the editor/writer, agent/writer relationship has changed since I broke in. I think that, number one, there are fewer old-school editors around. My editor puts pen to paper. No sentence of mine goes unchallenged, and he’s a wonderful editor, a wonderful line editor, but there are not that many around anymore, and there are a lot of acquiring editors who will take a book and then turn it over to a copy editor, and that’s pretty much it. There are so many editors who will say, “I can sell this. I’ll send it to the copy editor and we’ll sell it,” which has meant that a lot of agents have, in the last twenty years, begun to take on some of the traditional roles of the editor. They’ll get a book that’s good, but it’s not quite there, and they’re not going to want to send it off to the kind of editor who can’t fix it, and so helping to fix it becomes part of what an agent does now, probably more so than twenty years ago.

Lynaugh

How do you choose a point of view for a story? I’m thinking about Empire Falls and the multiple third person points of view, some of which are in the present tense, some of which are in the past.

Russo

I think it was one of those things I probably just did and thought about later. I can tell you why it works now, years after the fact, but at the time it just seemed, instinctively, like the right thing to do. The present tense is the most immediate, which is why it works so well in film, and why films are almost always written as, “He does, he says,” not, “He said.” It’s happening now.

I think time changes. When you’re young, the clock goes slower, and everything seems to be happening in present tense, because you don’t have that much past tense in your life. In Empire Falls, I was convinced that the point of view was right by the time we get to the final scene where John Voss comes in. That section begins with Tic speculating about the nature of time. Do things happen fast or slow? That’s what she’s trying to figure out as she sees John Voss coming across the parking lot. When I started writing that, I thought, Well, that’s kind of what her point of view is all about. It slows the clock down, it makes everything happen in a kind of teenage time, as opposed to her father’s time. As soon as we go to Miles’ time, everything goes much faster in third person and in past tense.

Edmonds

In the story, “The Whore’s Child,” Sister Ursula is in a fiction workshop, but she’s writing nonfiction. Have you ever considered writing nonfiction?

Russo

I just finished a long nonfiction piece for Granta. I’ve done a little bit of nonfiction before, but never anything as sustained as this. And it was a new experience. It’s a piece about the town I grew up in, Gloversville, New York, and it’s odd because I’ve been writing about that town throughout my career. North Bath, Mohawk, Thomaston, even Empire Falls, although the novel is set in Maine, those are all towns based on my hometown. In those, I was able to start there and just create a world, but re-imagine the geography, do all of that fictive stuff. When I didn’t know something, I made it up, but in this piece I had to call it Gloversville, and I realized I had a responsibility not to the kind of truth that I normally strive for, but to the literal truth of real people’s lives. It made me careful, cautious; it made me absolutely want to get things as right as I could, because I was writing about people’s lives, people who had real names and had experienced what I was writing about secondhand. I had to get it literally right, making sure that their names were spelled correctly, making sure that I understood that part of this was about the kind of lives, the really dangerous lives, that people lived working in the tanneries where I grew up. Those machines were deadly. I was writing about people who had lost arms up to the elbow, hands, thumbs, in these machines, as a result of doing what, back in the industry at the time, was piece work. Everybody got paid by the square foot of stuff they shoved through the machines. The machines had safety devices, which these men took off, because they were being paid by the square foot, and the safety devices slowed them down. They could not feed their family with the safety devices on, and they’d take them off, and work until they sliced something off.

I had been hearing about these machines all my life, but I found out that I didn’t actually know what a staking machine was or how it worked. I just knew it was real goddamn dangerous. I talked with my aunts and a couple of cousins who’d been in the mills and knew how all of this worked, because I couldn’t afford to be cavalier about it. I mean, if people have lost limbs in these things, I could at least figure out how they worked and where the danger was, and what it felt like to be doing this kind of job, what it felt like to disable a machine in order to feed your family, and what it’s like to know that the foreman, the guy behind you, turns his back while you disable your machine. Because he fully understands what you’re going to do and why, and he’ll turn his back so that he’s not a witness to you doing it. That stuff was important, and I had to get it as close to right as I could. So it was different—I should probably be doing that sort of stuff in my fiction, but it was suddenly very important to me to get that stuff right.

Lynaugh

Are there other ways it was different?

Russo

A lot of the mechanics of storytelling remain the same. You still make a decision, for instance, about what to include, because so much of this is about the dangerous work that went on in the tanneries, and the way that people were maimed and the way they were poisoned and later died of various exotic cancers. Because of all of the details, you find yourself realizing that you cannot put all of those things in the same section of the piece. In order for readers not to turn away, you have to take them out of that world and into a different world for a time, so that when they go back to it, they’re not so shocked that they’re tempted to skip through the pages to get to the part where they’re not in that horrible world anymore. You want to structure the piece like you would a story. You want the rhythms of fiction, even though you’re writing nonfiction. I would find ways to go into that world and come out, go back into it again, come out, so you get the shock, you get that sense that it bends both ways. Entering. Leaving. Entering. Leaving. It was almost like a gothic novel or a gothic movie, where you have those portions that are shot in the daytime—and you know, the very fact that it’s shot in the daytime, that nothing terrible is going to happen. But then you look at the sun going down on the horizon, and you think, “Oh shit, here we go.” You know the werewolf or the vampire is out. I found myself shaping this nonfiction in the way I would want it to work if it were a story. Even though it wasn’t fiction, I wanted it to read like fiction, to have the rhythms of fiction. I would ask myself a lot of the same questions. Too much here, too many examples? Break it off? Do it differently, does it work better here, does it work better there?

Edmonds

How did you handle dialogue?

Russo

There isn’t an awful lot of dialogue in this piece, and a lot of it comes from just a couple of characters, a couple of real life people. I was pretty scrupulous about making sure that I didn’t say anything that they didn’t say, either literally or figuratively. I wanted to make sure I caught the essence of what they were saying. But I did play with their speech patterns, in some cases, because I didn’t want to do dialect that would make them look stupid. I didn’t want readers to think that because people did these jobs that their experience was somehow crippled by their inability to describe that experience in language that the reader’s used to. But I was always striving to catch the emotion behind the dialogue. Is this a person feeling rage, feeling fear? I tried to use those fictional techniques, like, “He cannot meet my eye,” or, “He looks off in the distance,” or “It takes him a while to continue,” that same sort of attribution that you’d make in a story. You set it up the same way on the page.

Lynaugh

In the collection, The Whore’s Child, the story “The Farther You Go,” has a lot of similarities to the novel Straight Man.

Russo

That was the short story that Straight Man grew out of. I wrote that first, came through the conclusion, and I liked the character. I put it aside for a while and then went back and I could not surrender.

Lynaugh

Do novels often come out of shorter pieces?

Russo

More often, shorter pieces come out of novels. The Sister Ursula story in The Whore’s Child came out of Straight Man. Sister Ursula was once one of Hank’s students. He’s got the kid that writes the misogynistic ripper stories, and the girl who writes these flighty symbolic pieces, and Sister Ursula was there writing her story about her childhood. But it was so dark. I looked at it, and my editor looked at it, and Sister Ursula’s story is so dark that it just didn’t fit with the rest of the novel, so we yanked it out, and the story “Linwood Heart,” the final story in The Whore’s Child, the boy in that story was Miles Roby. I took all of that out of the novel because it was slowing the story down, and gave him a new name and some other things to do. So, more often, I’ll realize that there’s something really good happening in a novel, except it doesn’t belong there, and I’ll excise it and come back at it as a short story later.

Lynaugh

What kind of truth are you going for in your fiction?

Russo

Well, when you reduce something it always comes out sounding… reduced. But I think it’s the truth of the human heart. It’s when Miles Roby in Empire Falls, after fighting with himself throughout his life, realizes that being a father, and a good father, to Tic, and being an adult in Empire Falls, is better than being a child, because his mother wanted him to have a different life, and he’s always in some way or other, because of her sacrifices, felt that he’s failed her and failed himself, and has always tried to escape. That moment when he realizes, after almost losing Tic, that everything he wants is right there, that’s the truth of his heart. It should have probably been obvious to him and to everybody, but it wasn’t, and he struggled through 700 pages or so to arrive at a conclusion. It’s the truth of his own heart. It’s the truth of his own experience of life.

At the end of a book, I always want to meet at a kind of crossroads where there’s an understanding. I don’t want to say a strictly intellectual understanding, but the character arrives at someplace that’s different. But for the reader, I want there to be real emotion to that. I want the reader not just to understand something, but to be profoundly moved. Take Bridge of Sighs. He begins the novel by saying, “We’re going to Venice. My wife and I. We will be going to Venice. We are going to visit our old friend Bobby. I’ve never traveled, but we’re going to go.” At the beginning of the book, he’s lying. At the end of the book, the last line is, “We will go.” And this time we believe him. Because that enormous journey he’s taken is from one sentence to the same sentence. A thousand pages later. He returns to his initial statement, except this time it’s true. There’s an element of human understanding in it, but I’m hoping that when that moment strikes the character, it hits us as readers not in the head, but in the heart.