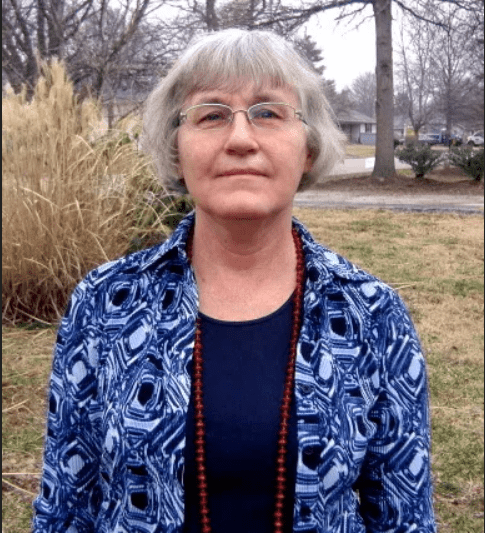

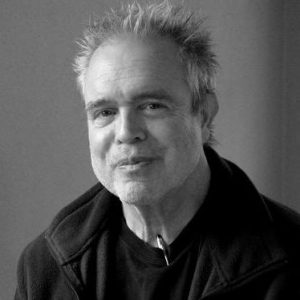

About West Trexler

Wes Trexler is a writer, musician and abuser of vintage sailboats based in New York City. He was a founding member of the glam-punk band Hotter Than A Crotch, and driving force behind the short-lived Brooklyn underground DIY venue Club Plantation (2012-2013). He is an adventurer, a hustler and political radical who writes, performs, and organizes under various pseudonym. Born in West Virginia amid great natural beauty and crippling poverty, storytelling was in his genes. His grandmother Zelda, who’s still alive and well, used to write for the local newspapers back in the ’50s and ’60s. His other grandmother taught English for many decades, starting out in a one-room school house at age 17. She could recite pages from the Canterbury Tales from memory well into her eighties. Mr. Trexler has been up to no good recently, traveling in South America and Nepal for months at a time, living for years with no visible means of support. He has a problem with authority and hates cops more than anyone you will ever meet. He was once shipwrecked on a deserted beach inhabited only by wild horses. He thinks people should unplug their TV set and go live a life worth writing about. He is a graduate of the Inland Northwest Center for Writers, and attended the Squaw Valley Community of Writers in 2005.

A Profile of the Author

Notes on “North Jutland Blues”

The thing you should know about “North Jutland Blues” is that a decade elapsed from the time I wrote it to the time it was finally accepted for publication. If the idea of a ten-year lead time to sell a hundred-dollar short story seems crazy, then you don’t understand what it means to lead a life in the arts.

It’s actually the first story from a collection of shorts I did years back that has yet to be published as a whole. I’ve sold a few of them recently, but “North Jutland Blues” was always one of my favorites. It was the first story I wrote where I felt I’d stumbled upon a genuinely original voice, and that voice and that protagonist became the heart of the story collection (titled Legend of the Night Shark).

After failing to find an agent for Legend of the Night Shark, I let it mellow for a couple years while I was busy making music and putting out records in the Northwest and New York. Then, a few months ago, as I neared completion of a very hefty nonfiction manuscript, I decided to sell the Night Shark stories off on their own. Enough time had passed that the constant volley of rejections lost their emotional sting. It was hard to care about stories written so long ago they seemed to be part of some other guy’s efforts, and I was much more interested in getting rejections for my next project.

What strikes me now, looking at it from a whole different epoch in my life, is the haunting desperation that lies beneath the wide-eyed abandonment and directionlessness of the narrator. There’s no way I could have written that story in 2015, and I’m glad I didn’t wait. There’s no doubt I would have made different choices had I composed it last week. I’m a different writer now, but the story as it is seems more honest than if I’d tried to substantially rewrite it.

Another thing I notice is the thematic consistency that is still present in my work. I’m still obsessed with jazz and entheogens, with stolen bikes and people-in-motion. These are all still prevalent themes in almost everything I write. The people I write about are always on their way somewhere, dodging something, driving a pickup or hopping a train, chasing or being chased into dark allies. My characters are always running after back-and-forth propositions, looking at their lives through that rearview lens which often consumes our thinking when we hit the road, when leaving a place or en route to somewhere new.

I decided a long time ago that I could only write fiction that’s set in places I’ve been. There’s no way for me to be really convincing about a scene if I don’t have access to the sensual rush of details that comes from reliving a certain place. Of course we all think of character as the building block of good fiction, but to me place is equally essential. There’s only so much you can do inside a character’s head. To keep me engaged as a reader, I need to be able to feel the setting, and without the depth of convincing place details, I lose interest in the character’s inner turmoil. So, like all my stories, “North Jutland Blues” was inspired by things I saw firsthand, in this case things I saw in Denmark many years ago.

I think the narrator is somewhat oblivious to his own turmoil, and it’s the internal strife of the Danish character Klaus that is more obvious on the surface. You essentially have two characters who are both incapable of dealing with whatever emotional vexations are plaguing them. The narrator seems to see himself from the outside, and he’s close enough to Klaus to see his conflict for what it is, but still he’s not really able to do anything with the insight. If loneliness and rejection is what’s bothering these guys, they sure don’t do much to remedy the situation.

A lot of my stories have a similar emotional undercurrent: lonesome people in search of ecstatic moments. I think that also sums up a lot of what life in Scandinavia is like, and the title of the story really broadcasts that idea from the very start.

Notes on Reading

Some writers write because they have something to say about the world, others write because they have something to say about the particular literary tradition they belong to. Either pursuit is valid, and we all do a bit of both, but I’m definitely in the first camp. It doesn’t matter to me one bit what’s happening in contemporary literature. I make it a point not to read any books by authors who are still alive. You could spend your whole life reading things that are hip, but who knows if anyone will still care about those books in twenty or thirty years? I prefer to spend my time reading books that have been vetted by time, works that still seem relevant after a few decades or a few centuries, things that have influenced everyone before me.

The older stuff is best for me because I find myself mining them for vocabulary. Any Mark Twain story will teach you a dozen technical terms, pieces of antiquated jargon, or bygone slang you won’t likely run into elsewhere. When I read newer stuff I don’t pick up as much. Contemporary writers have pretty much the same vocabulary as I do, so there is less immediate reward for the effort.

I think the way I was taught to read in grad school ruined my love for fiction. I didn’t read any fiction for a couple years after getting an MFA. I wasn’t able to read for the sake of reading, I was only able to study the fiction rather than just enjoying it for the storytelling. To this day I don’t read fiction at nearly the rate I did in my twenties (my “book devouring boyhood” as Kerouac put it). Now I gobble up news and newsish pieces, historical Anarchist propaganda, science articles, political commentary, citizen journalism, anything that spreads my consciousness to the real human experience, anything that fills me up with true details or bizarre ideas. I love this notion that the pursuit of wisdom and the pursuit of scientific knowledge seem to be coalescing in our times, and there are a million rabbit holes out there you can dive into and kind of instantly absorb other novel ways of looking at the world.

That being said, there are a few authors I can’t stay away from, the guys whose language is such a part of me that no amount of pedagogical scrutiny can dull my enjoyment, the writers who seem always to be speaking directly to me. I’m talking my personal triumvirate of lit heroes: Faulkner, Burroughs, and Dostoevsky. If you only read those three authors, it’s hard to say what you couldn’t learn about storytelling and the art of the line.

Faulkner is a Southern country boy like me, so his stories always have this collision of highbrow ideas and lowbrow characters. There’s always this tension between the genius of the narrative voice and the primitive, earthy insanity of those he is describing. Whenever I look at my own work, and it seems too protracted or too risky, or too heady, I reflect on Faulkner and his boundlessness. There’s no way that readers today are less sophisticated, or less receptive of daring, challenging prose than the readers of 1930s America, at least I hope not. So, I find myself asking, “Would Faulkner try to get away with this?” “Would Faulkner ask this much of his audience?” Few of us would dare to give multiple characters the same name in one book, and just leave it hanging like that, but Faulkner did. He gives me permission to go out on narrative limbs when I need to.

William Burroughs I love because his work, I think, managed to escape the realm of hip writing and end up in the canon of visionary thinkers in fiction. He inspires me to stick to my vision no matter how opaque it might seem to others. So much of what he does is both fantastical and hyper-real. He is a true surfer of the universal subconscious, yet, in the end, there is nobody grittier, realer than Burroughs. He proves that you can draw on the dream world for images and ideas without losing touch with the concrete stuff of humanity, the stuff that keeps us interested and engaged. I also like the way he can write about his own experience, use a version of himself as a character without sanitizing it. He and his narrators are well acquainted with their own shortcomings and flaws, acutely aware of them. We want to believe what his narrators are telling us because they seem so honest in their self-criticism, so unrepentantly human, warts and all.

All of Dostoevsky should be read and reread. We English speakers are at a great disadvantage here, since we can only look at translations, and there is no way for us to really experience the innate poetry of his language as it was meant to be. Nonetheless, when you look at his books you see the work of a man who was born to tell the story of his time and place, to become the official critic of his people. For the fiction I write, this is often the goal. I want to recreate my world as a literary universe, to dissect it and present it as though it were the only possible interpretation. This is what Dostoevsky does. His descriptions are so adept that there is no doubting their authenticity.

For writers, I think it is especially important to look at his Notes from Underground. This was his debut novel, and a very short one at that. When you read the work of young Dostoevsky, you can see that there is the capacity for genius, yet Notes from Underground is hardly what you’d call a masterpiece. So, how did he go from writing a great, interesting, flawed little book about Russian society to writing undeniable masterworks like Brothers Karamazov or Crime and Punishment? The unfortunate answer is hard work. True, he was born with the capacity for genius, but that doesn’t guarantee a masterpiece. The difference between young Dostoevsky and later Dostoevsky isn’t the result of a shift in the innate intellect of the author, but the result of years of craft that went into producing ever-greater works of art. You may be born with the capacity to create high works of art, but without the decades of toil and creative productivity, the genius has no way to express itself. Dostoevsky worked his way up to creating masterpieces, but he started from fairly humble origins, and that is one of the best lessons we writers can take to heart. Being the brightest smart-ass in a grad workshop isn’t the same as writing a genre-defining tome that will be studied and enjoyed for generations. Don’t mistake one for the other.

The other not-necessarily fiction writer I keep coming back to is Walt Whitman. His non-fiction Specimen Days has informed my style as much as Bukowski or Steinbeck or any of the Beats, and his descriptions of old New York and Civil War America are absolutely essential to understanding our cultural history. And, for understanding how lines work, how words can change shape and grow and shift infinitely, there’s nothing better than Leaves of Grass. His habit of spinning off long breathless lists of images and concrete details to expound on an idea, or to create an emotional sweep is something I definitely emulate. My more recent nonfiction works rely heavily on Whitmanesque litanies to create scene and mood, to document real world events I’ve been witness to.

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.