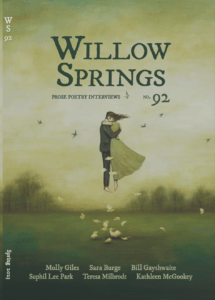

Found in Willow Springs 68

Back to Author Profile

A TRANSFORMATIONAL EDUCATION, the newspaper ad had promised, so we'd come to the Gilchrist School, which looked like a 19th century invalids' home. With its damp-streaked stone and clinging pine trees, it seemed ideal for transformations, a place where a person could go romantically, molderingly mad. Here no one would find me until I was done. For the first twenty minutes of my interview, Mr. Pax, the headmaster, poured words upon our heads and seemed to require none from me. I had only to sit while he spoke of the crimes of modern education, the importance of avoiding the craze of the moment and what he called "the great, all-too-often meaningless noise of exhibition," how he thought of teaching as a process of shaping, honing, turning each young woman into the best possible version of herself. My mother, who had never been anything but her own best version, smiled winsomely and told him, "We would just lost to see Melody blossom, that's all." Yes, yes, Mr. Pax said.

But then he inclined his great shining white-ringed head toward me and said, "Well, Melody! You've been quiet, for a person whose name heralds such mellifluousness! Please, tell me something about yourself. What activities do you most enjoy?"

A pause. Then, "Go on, Melly," my mother said, for all the world as if she expected me to rise to the occasion, except there was a little too much brightness in her voice. Had she really expected it, of course—had I ever shown any signs of such a capacity—we would not have been here.

I dropped my eyes to the carpet and scoured my days for things I could speak of safely. School, which I hated. Television, which I knew better than to talk about here. Sleeping, which I liked, except when it ended. Drawing, a loose word for what I did sometimes, tattooing pages of computer paper in rhythmic, soothing swirls of ink. Reading Nancy Drew mysteries, sticking and unsticking the pads of my fingers to their bright yellow, plasticky covers until I knew they were tapestried in whole invisible galaxies of my fingerprints. I never had anything to say about them when I finished them.

"Reading," I told Mr. Pax. The word came out scratchy and prematurely old. I hadn't talked much in the car.

"Superb!" He clapped, actually clapped, his hands. "And what are some of your favorite books?"

Somehow I had failed to foresee this, though the floor-to-ceiling shelves on the wall behind Mr. Pax were lined and lined and lined with books like dull, uneven teeth. If I pretended to have read something impressive, Mr. Pax would certainly roll his chair over to the shelf and pull it out, set it right down on the desk between us for discussion. I could see myself sputtering and flecking the dusty damning rectangle of the book with spittle while my parents sagged.

"Mysteries," I said. "Mostly."

I waited for Mr. Pax's face to fall or flush with anger, for him to throw up his hands and cry, This! This I cannot transform! Instead he gave me a wide, warm illustration of a smile. "Ah, the pleasures of the whodunnit," he said. "The neatness of the ending, a satisfaction that all too frequently evades us in life. You know what I've found to be true, Melody? A taste for mysteries is often the sign of a truly orderly mind."

My mind is truly orderly, I thought, cheeks reddening with a hope and gratitude that dizzied me because I had been so unprepared for them. And next: If this man wants to try to change me, I will let him.

WE HAD DRIVEN to Gilchrist intending only to have a prospective-student visit, but after the interview my parents decided to leave me there that very afternoon, before I had a chance to lose something or fail to follow through on some simple instruction and force Mr. Pax to reconsider his assessment of me.

"You don't have to stay forever, of course. Let's just see how things work out," my mother told me at the school's front doors, where my father had already collected his umbrella. "We'll send your clothes and things straight away," she said. She leaned in to kiss me, leaving behind a crisp little cloud of her perfume. I wanted them to go—I wanted Gilchrist to begin on me—but there was something about the idea of my mother sorting through my clothes and boxing them up, my father driving to the post office with them in the trunk of his car, that made me feel as if I had died somewhere alone the way without noticing and would now be expunged. My throat began to close with tears. I told myself that the next time they saw me, I would be so polished I would hurt their eyes.

"I have tons of clothes she can borrow until her stuff gets here," said my new roommate, a girl named Molly Briggs, in a cheerful defiance of the fact that nothing she would own could possibly fit me.

"Well thank you, Molly, that's very nice," my mother said. My father gripped my shoulder. I knew he tried to put things he couldn't say into that grip.

And then the door banged shut behind them and they were gone.

"It's amazing here," Molly said as she led me to the dormitory wing. "You'll see." She swung a door open into a small square of a room, kindly pretending not to notice that I was crying. "I'm super excited," she said. "I figured I'd get a roommate eventually. I was the only one with nobody. Odd number." I went in a sat on one of the desk chairs, trying to whisk my eyes dry with soggy fingertips. "Let's find you a dress for dinner," Molly said.

"That's okay," I said thickly.

Molly surveyed me. "We all wear dresses here, though."

"All the time?"

"Mr. Pax says how you look is the first impression you make on the world." She was in the closet now, pushing hangers aside with a brisk metal sound like the opening of a shower curtain. "And the easiest part to control."

I glanced down at my lumpish, besweatered form. My experience held no support for that idea.

"Here's the one I was looking for," Molly said.

The dress was black and had a forgiving enough stretch to contain me. I sweated through it almost immediately at the armpits, but the color didn't show. Dresses, I thought, as I pulled at its hem. We all wear dresses here.

THE HATS I LEARNED ABOUT a few days later, when I tried to take my copy of The Mystery of the Lilac Inn outside for lunch. This was allowed: lunch and dinner were served on gray metal trays that you could take wherever you wanted to go. At lunch you just had to be back at the tables by half past twelve for Assembly. Routine was sacred at Gilchrist—the days were shaped to run in a smooth way that made your level of contentment mostly irrelevant—and so I felt unfairly accused when I looked up from the tricky balancing project of my tray and book and found Miss Caper in my path.

"Where are you off too? Outside?" she asked. tugging on the hat string tied beneath her chin, gazing at me from beneath the brim. The rapid fumbling of her fingers made her look even younger than usual, and always she looked young enough that the first time I'd seen her, standing before her blackboard full of notes on Tess of the D'Urbervilles on my first morning at Gilchrist, I thought she was a student.

"There's time still," I said. "Right?"

"Oh yes. Just—it's bright out there. Why don't you borrow this?" She'd succeeded in working the knot free and before I could respond she settled her hat on my head. It shaded my view of her. She was already moving off toward the faculty table, but I saw her stop and lean briefly over Molly, who looked in my direction and hurried toward me with a tube in her hand.

"Here," Molly said, squeezing something onto her fingers, and then she rubbed it—cold, cold—onto my face. Holding my tray the way I was, my hands couldn't stop her. "Sunscreen," she said. "We wear it when we got out in the daytime. Hats, too."

"Why?"

"The skin," Molly said, "should be like a beautiful blank page."

Outside, I sat under a tree. Nancy was about to figure out what was going on with the ghost, but I was having trouble paying attention. The paper of the book itself was distracting me, its even , frictionless fell beneath my skimming fingers. A caterpillar fell onto my lunch tray, into my salad dressing. I watched it writhe.

At twelve twenty-five I closed the book and carried everything back in to rejoin the thirteen other girls in my year at our table. I banged my knees as I took my seat, and they all turned in my direction, no particular expression on their faces, before settling again into elegant disinterest. I sat there feeling, as always in such moments, my mother's eyes on me.

Mr. Pax rose. Every day he made a speech to start Assembly. I had been listening as closely as I could to each of them, filing away as much as possible in the hopes that it would teach me how to become what everyone was trying to make me. I think that even without the effort I would have remembered whole sentences—he had that kind of voice, those kinds of words. To unlearn an old habit, I believe, takes more diligence than to learn a new one, he'd said to us yesterday. The day before: Remember that the true intellect requires so much energy to sustain that it has none left over to devote to display. It would not have occurred to any of us to equate his speeches themselves with the display of which he spoke. Though Mr. Pax strutted daily before us, shone, dripped words like syrup, everyone knew that this was not artifice. The artifice would have been to prevent himself from doing these things.

Mr. Pax centered himself at the front of the room, and turned to us. "Today, girls, I thought I might share with you a brief history of Assembly itself."

He waited while small conversations quieted. Molly swiveled toward him in her seat.

"When I came to Gilchrist, more years ago than I would care to disclose"—the faculty, lined behind him at their table, tittered softly—"I came armed with the belief that education is nothing less than the shaping of the soul. Thus, upon my arrival, I had to ask myself: These souls entrusted to me, what form ought they assume? What shape would best suit them? It was question neither asked nor answered lightly, but eventually, an answer did come. I realized that I wished to mold not future citizens of the world as it was, but of the world as it should be. For it is my belief that the world around us has lost the grace and purity it had in earlier times, girls. That does not, however, mean that you need to do so. It was—is—my deepest wish to prepare you to stand in loveliness before eyes that no longer see as they ought, to answer with eloquence the questions of those who may or may not be capable of appreciating what they hear. I believe this sort of deportment has value no matter how it is perceived. At the end of the day the world is not my concern. You are."

The skin on my arms prickled. I ran my fingertips lightly over the bumps, trying to settle them into blankness.

"In light of all of this, I consider Assembly a sort of training ground, if you will, for your lives to come. When you stand and make announcements—even if you are simply questing after lost items or marking the anniversaries of one another's birth—you are practicing being seen and heard. And it is my most cherished hope that you are also considering, deeply, how you wish to appear and to sound in those moments."

I scanned the two lines of girls at my table, the willowy form and smooth smooth faces, behind each of which was fluid voice at the ready. I knew just how I wished to appear and to sound. Any minute now I would understand how it was done.

ON A CRISP TUESDAY near the beginning of November, Miss Caper stood in a patch of sun at the front of the classroom and talked to us about Keats and negative capability. We watched her form our desks, which were arranged in a circle and which were the same as the desks at my old school, chairs barred to the tabletops to prevent the tiltings-back of unruly boys. Not a one of us, of course, would have been inclined to tip. Miss Caper wrote, "'Ode on a Grecian Urn,' 1819" on the board, rounding the letters prettily. Then she put down the calk and began to read to us in a low, thrilled voice: "Thou still unravished bride of quietness, / Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time. . ."

She read the whole thing, though we had also read it for homework, while we clicked our pens or wrote the title and date we already knew in our notebooks. When she finished she looked up and breathed deeply. "He was twenty-four when he wrote that," she said. I had been thinking for a couple days now that Miss Caper might be a little in love with Keats.

She asked us what we though the poem meant. I never volunteered at these time, since the potential cost of a wrong answer matter much more to me than the potential benefits of a right one. The other girls were not cruel—we were kept too busy for cruelty—but I didn't trust them. They mostly ignored me, even Molly, who often seemed oblivious of my presence, in a friendly way, while were actually speaking. I had not become the way they were. I tied my hair back into the right modest knot, and I wore the right things, the hats and the sunscreen, the dresses. But my skin had stayed freckled instead of going paper-blank. No new smooth voice had blossomed in my throat. And the dresses did nothing to make me look like the others, who filled their own with foreign undulating shapes.

Miss Caper called on Lila, who was talking about the imagery of the poem, which she really thought was just so powerful, when the bell ran. Lila stopped talking instantly. "'Eve of St. Agnes' for tomorrow!" Miss Caper told us, as we closed our books and began to file away from her. "Answer the questions at the end of the poem please."

"Melody," she said then, shocking me to stillness, "a moment?"

She leaned against the edge of her desk. I walked back and stopped, leaving a safe berth between us.

"Have a seat," she said, pulling one of the desks out of its circle, closer to her. I sat. "I've been asked to speak to you. You've been here over a month now."

Words rose within me, tasting of panic, please for more time and promises of improvement—but I knew that if I tried to release them they would only clog in my throat. I waited. Miss Caper's eyes flicked back and forth between mine, as if the right and left were delivering different messages to her and she were trying to decide which truly reflected my feelings.

"We think you're fitting in nicely. Really we do. You do remember what Mr. Pax says about the outside and the inside, though?"

I tried to call up the words, which I recognized from one of his recent speeches, maybe even yesterday's. Miss Caper gave me only a few seconds before filling in the answer herself. "He says that the outside should as nearly as possible match the quality of what's within. That way, we do everything in our power to give those whom we encounter the right expectations. So a beautiful person, like you, should do her best to look beautiful."

She paused again. "Melody," she said, and her voice suddenly had the same low thrum it had taken on when she'd recited the Keats poem, "how would you like to look a little more like a Gilchrist girl?"

Without waiting for an answer, she walked over and opened a closet I had never noticed in the corner of the room. From within it, she produced a hollow stiff shell, trailing long tentacular laces: a corset. There was flourish in her wrists as she held it out to me. A new form, right in her hands, ready for handing over.

AFTERWARD, I SWISHED MY WAY up the stairs, pausing every two to breathe, and into our room.

Molly had been reading on her bed. "Oh thank God," she said when she saw me. "I was getting so sick of having to get dressed in the bathroom. I don't know why they didn't just let me tell you. Miss Caper laced you up?"

I nodded. Miss Caper had, after turning away discreetly while I closed the front of the thing around myself. The pulling of the stays had hurt. I had not made any sound, though. I told myself I was having every faulty disappointing breath I had ever breathed squeezed out of me.

"Let me see." Molly stood and slid a hand down the back of my dress. She tested the stays with a practiced finger. "Not very tight," she said. "I'll do it better tomorrow. We can lace each other now. All year I've been having to knock on Marjorie and Kate's door and get of them to do me."

The next day at Assembly, as I ate with my back straight under the force of the lacing, which seemed to be pulling me together in entirely new ways, Mr. Pax stood and said, "Miss Caper tells me that the ninth grade has just completed its study of Keats' 'Ode on a Grecian Urn.' A wonderful and wise poem: 'Beauty is truth, truth beauty. . .'" He let his voice linger, "One of the truest, most beautiful lines ever written, perhaps. For our surroundings are so often ugly, girls. Why should we not strive for beauty and bettering where they are within our reach?"

His eyes brushed lovingly over us, then. I could have sworn that they paused for a special instant on me.

IT DID FEEL, AT FIRST, as if I were moving within a body I had strapped on. My torso was suddenly unbendable: a stiff column that I had to swivel my hips to move when I walked. I couldn't quite breathe in fully, either. But it's surprising how rarely a person needs to breathe to the very bottom of her lungs in a day. Everything they asked of us at Gilchrist—the essay writing, the graphing of functions, the discussing of literature, the announcing of one another's achievements at Assembly—could be accomplished while talking no more than refined sips of air. It was only when somebody worked herself up that there was trouble: the time that Marjorie had a tantrum over her essay grade in English, for instance, and went very red and then slumped to the floor. Miss Caper produced smelling salts from her desk drawer and stroked Marjorie's forehead while she came around. I watched from my own desk and breathed evenly through the whole thing.

There was some pain: a compressed feeling and a periodic but deep ache in the ribs. I took satisfaction in this. It seemed to me proof of payment. Quickly I came to feel, when I took my corset off to sleep at night, a disbelief that I had once walked around in that state, so unsharpened and unsupported, so greedy in my consumption of air and space. Our lacing-up in the mornings became a companionable thing between Molly and me. She was determined, much more determined than Miss Caper, hampered by gentleness, had been. One morning, after a couple of weeks, she finished pulling at me and then tugged me over, back first, to the full-length mirror on the inside of our door. "Look," she said. I peeked over my shoulder. "See that bump in the laces there? That's as tight as I used to be able to get them." I did see it, a rut of a place like where the lace of an often-worn shoe hits the bracket, easily an inch below where the know was now. Visible proof of what was being accomplished.

I turned back to her. "Tighter," I said.

"Tighter? Mel, it's already—"

"I want it tighter," I said. While she pulled, I closed my eyes to imagine the moment in which my mother would first see me again. Her face before me, her eyes widening at my new swell-dip-swell, her smile knocked out of carefulness.

Other changes came as my shape shifted. The other girls were still not exactly my friends, but I could feel the distinction between us blurring. Sometimes they would call me over in the dining room even if Molly wasn't with me. I wrote letters to my parents (we were big on old-fashioned letter writing at Gilchrist) in a chatty voice I honed with pride. "Math will never be my forte," I told them, "but we all have our limitations! Hope you enjoyed the weekend with the Bermans!" In classes, I now spoke occasionally. I had realized that the teachers were so generous that they would mostly spin a wrong answer right for you. Miss Caper seemed to have taken a particular shine to my reading voice. She called don me more than anyone else in the rotation. I read the Brownings, Tennyson:

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

"The Lady of Shalott's death," Miss Caper said, "is inescapable once she sees Lancelot, and then rises from her loom and looks to Camelot. Why is this, do you think?" she asks me. "What is the nature of the curse?"

"I guess," I said, "it's like she's supposed to be separate? Because of the weaving? So when she leaves she wrecks it?"

"Good," Miss Caper said.

Then she called on Melissa Clearwater to read "The Kraken." I let my hands drift for a moment to my waist, my habitual test, the patting-down of my dimensions. They were changed, they were definitely changed, and sometimes this brought comfort. Other times, the curve in my waist would feel too gradual beneath my palms, and I would press myself tight in fear. I was not yet changed enough. I would have to do better.

I found, with time, that the harder I tried to resist these tests—the more I tried to reassure myself that they weren't necessary, that of course my waist was becoming smaller and smaller with each day—the greater was my need for them.

One afternoon, a few months into my wearing of the corset, Mr. Pax almost ran into me in the hall. He had his head down, bulleting forth to something important. I sidestepped him at the last instant and wobbled, my balance threatened. He looked up in surprise, then smiled. "Excellent save!" he said, reaching out to steady my slipping books. "My apologies!" He leaned back to look at me more closely. "I must say, Melody," he told me, "that I hear wonderful things about you. I am very pleased."

He moved off down the hall and left me filled with such raucous joy that my heart rocketed and dappled my vision in shimmery patches, and I had to take very deliberate, measured breaths to steady it. For a moment, I felt sure of how far I had come.

THREE WEEKS BEFORE the beginning of spring recess, our poetry reading in English took a sudden turn. Miss Caper arrived bearing two stacks of brand new, slim volumes, which she passed around the room.

"Page thirty, please," she said. "This poem is by Su Tung P'o. It is called 'On a Painting by Wang the Clerk of Yen Ling.'"

She began to read: "The slender bamboo is like a hermit. / The simple flower is like a maiden. / The sparrow tilts on the branch. / A gust of rain sprinkles the flowers. . ." Her voice was still hesitant on the new stripped-down rhythms.

When she'd finished, we were quiet for a minute, trying to decide what to make of what had just happened. Finally, Molly raised her hand. "How is that a real poem, though?" she said. "Where's all the description? And the rhyme and everything?"

Miss Caper signed. "There is a very deep, modest kind of beauty in the poem we have just read, girls. It is a beauty that stems from rendering a thing precisely and quietly in words." All of this sounded all right, but she looked somehow off-balance with such a small book in her hands. "This poem is made of a series of perfectly captured moments. I think you will come to understand as we continue to read. You'll be working with pages 32-38 of the anthology for your assignment this evening."

I stared down at the book before me. I lifted it, and its lightness made me anxious.

"But I though we were reading 'Aurora Leigh' next," Marjorie said.

"As did I," Miss Caper told us. "But the headmaster wishes to make a change."

Around this time, one of the sixth graders—Lizzie Lewis, a pixie of a girl with a great mass of black shining hair down her back—stopped showing up for meals, even Assembly. The sixth grade at large reported that Lizzie no longer came to classes, either. Our curious whispers gathered momentum as the days passed until finally Miss Ellison, our math teacher, had no choice but to address them, if she wanted us to focus on the quadratic equations she had written on the board. "Lizzie is receiving special lessons from Mr. Pax," she told us, "for which she requires focused alone time." We could tell from the falsely confident way she said this that Miss Ellison didn't know what was happening, either. Still, Lizzie's continued absence gradually became old news; we stopped talking about it because there was nothing new to add and mostly forgot her.

I spent spring recess at Gilchrist, where I had also spent Christmas vacation. My parents seemed always to be traveling during the times when I could have come home: Bora Bora, an Alaskan cruise. My guess was that they were unwilling to trade the newly poised girl they glimpsed through my letters a flesh-and-blood me who might disappoint them in familiar ways. Time seemed to soften and stretch long in those two weeks. I missed Molly and her lacing. I couldn't get Kate, the only other girl from our year who had stayed at school for the break, to pull as hard. I knew for a fact that the ground I had gained was receding, because I could reach back and feel the from the lacing that I had eased back into the ruts I thought I'd abandoned for a good week, two weeks earlier. When I touched this proof, this record of my spill back over the lines that had been drawn, I was filled with a sense of powerlessness that made me bit my tongue until I tasted metal. At night, I got out my old Nancy Drew books and ruffled their pages, the furred soft sound of the paper like another person's breathing in the empty room, but even they did not let me sleep.

I would feel better once the others were back, I told myself. And anyways I had changed. I knew it. Yet it seemed to me, that in the dark, that nay progress that could be undone in this way was not real progress at all. A nightmare vision haunted me of the first day of summer vacation, being driven home in my parents' car, its smell of leather and bits of food I had dropped over the years as familiar to me as the smell of my own body. I would see in my parents' faces, each time they snuck looks at me from the front seat, the brief flight and then the dead plunge of hope—teaching me over and over that I would always be the same as I had ever been.

ON OUR SECOND DAY back in session after the break, Mr. Pax stood up at Assembly and said, "I am sure you have all noticed that Lizzie Lewis has been gone from your midst for some time."

None of us had thought about Lizzie in weeks, but we nodded solemnly.

"Lizzie has undertaken a special project for me," Mr. Pax told us. "This project has regrettably required her temporary absence from your company. But she is, at last, ready to rejoin you, and ready to show you the fruits of our labor. And what fruits they are, girls!" Or will be, when they have ripened fully."

He paused and smiled at us. "You see, Lizzie is on her way to attaining a very ancient form of grace. One that will soon be made available to the rest of you, though it will be a bit more complicated for those who are older and have already grown more than Lizzie. Her initial break has been made, but that is really only the beginning, of course. The binding process itself will take some time, indeed, to achieve the desired result."

We gasped in a united breath, straining our laces.

Miss Caper stared at Mr. Pax, her face rigid. Sweeping the room with his eyes, Mr. Pax found hers; he help them as if this were a matter of will, though he was still smiling. Finally, Miss Caper looked away.

"Recovery is still in the early stages," Mr. Pax said. "There are no shortcuts in a process like this, girls. Walking remains for the future. So you'll pardon our rolling entrance. Lizzie, my brave butterfly!"

He stretched his hand out in a summons. My eyes flew, with everyone else's, to where he pointed. But in the pause before Lizzie appeared, I saw others in the empty doorway, others I knew I was the only one to see. Each came in turn, without hurrying, to take her place in the line. I knew them all instantly. The Lady of Shalott, bent from her loom and yet graceful, one of her ivory arms banded in bright thread. The simple flower maiden, petal-cheeked, lilting as if in a breeze. Nancy, with her blond, metal-gleaming hair and the pressed slacks that fit her like her rightful skin. And my mother, my ever-lovely mother. My mother with perfection itself in her face. She moved, with the others, to the side, and then turned back toward the doorway.

Then came Lizzie, the real Lizzie, in a wheelchair pushed by Miss Ellison. Lizzie bore her abbreviated feet before her, propped on the rests: time hoofs of feet in child-sized slippers of a vivid emerald silk.

It was a slow entrance, a grand one. There was pride in Lizzie's smile. Also pain, but that was the price, as all of us at Gilchrist had already learned. And if her pain was greater than anything we had yet experienced, what she had bought with that pain was proportionately greater, too, I though: a change that was not reversible. Lizzie would never have to sit in her room and tilt her folded feet this way, that way, wondering if a slow slide had begun that would carry them back to their previous dimensions. She would know that this was impossible. Here at last was certainty. Lizzie would feel the proof of her new and more beautiful self with each step she took after this, each hair's breadth of a footprint she left behind her, the way all that had anchored her to ordinariness had been whittled down to a fine, sharp point.

I caught the sight of Miss Caper's face. It had gone very white; her eyes were wide. She saw only the pain, I thought, and not that the pain was for something. I knew there had been agony for Lizzie in getting to this point, but I also knew that nothing could hurt her after this, in any important way.

My mother and the others who had preceded Lizzie into the room were still there, but they were watching me instead of Lizzie now. Their gazes were steady, approving. I turned to look at Mr. Pax, our great shaper, whose face was red with triumph. I though that I was ready to feel my bones break between his hands.