Found in Willow Springs 56

January 21, 2005

Joal Lee and Brian O'Grady

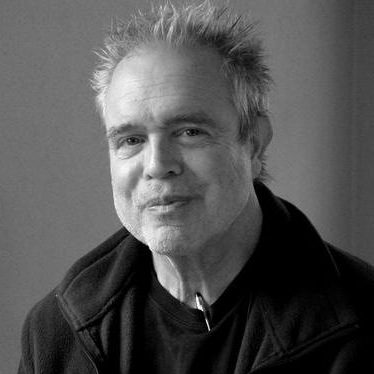

A CONVERSATION WITH LAWRENCE SUTIN

Photo Credit: Blackbird

Lawence Sutin grew up in the Twin Cities of Minnesota. His parents, whose oral history he chronicled in Jack and Rochelle: A Holocaust Story of Love and Resistance (1995), were Jewish partisan fighters during the Holocaust. “Given that I was raised in a family where there was a legacy of pain,” he says, “there was a middle time in my life where I simply needed to be on my own and find out who I was.” A Postcard Memoir (2000), his collection of lyric essays in dialogue with samples from his postcard collection, reflects a self-awareness that is gentle, affable, and dark. He is also the author of Do What Thou Wilt: A Life of Aleister Crowley (2000) and Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick (1989).

Though he knew from a young age that he wanted to write, he early on pursued a degree in law from Harvard University, he says, “out of fear of the world.” Currently he teaches in the MFA program at Hamline University in St. Paul and the low-residency MFA program at Vermont College.

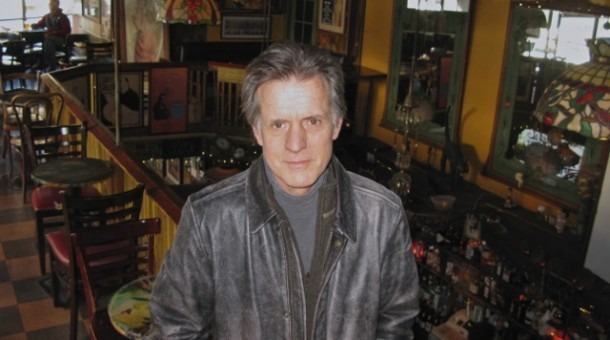

Mr. Sutin was interviewed over lunch at the Silver City Grill, in Spokane, Washington.

BRIAN O’GRADY

What is a typical day or week of writing like for you?

LAWRENCE SUTIN

I write, say, four or five days a week for roughly three to four hours. I like to work steadily. I have come to a point in my life where if I don’t write for a few days I actually miss it. I’m not one of these writers that has to drag themselves to the desk, feeling a great sorrow about the difficulty of the task at hand. Writing is a tremendous joy and I’m fortunate to get to do it.

O’GRADY

How long did it take you to get to that point?

SUTIN

That’s a good question, because I had always wanted to be a writer, but by virtue of always wanting to be a writer I became very frightened of it because it meant so much to me. What happened was, as an undergraduate I wrote something that a writing instructor really liked that was almost published in the Antioch Review, and when it was not I went through a kind of despair and a few years of writer’s block. So in my later twenties I had to fight through a kind of anxiety about the writing process, which I did with might and main and ever since then I’ve been very careful to like it very much. So, yes, I went through some difficult years getting on my feet as a writer, believing it was something I could be, overcoming the sense that it was exalted and unapproachable, which I think is a tremendous mistake for writers. Obviously, what you have to do is write a great deal and achieve more and more comfort and intimacy in the process.

JOAL LEE

Did a specific incident change that for you?

SUTIN

I wouldn’t say there was a specific incident, no. I think it was my own realization that the only way to develop as a writer was to put aside all those self-critical and anxious reasons that would deflect one from doing so. Those were barriers to my realization and happiness—you just train your mind to stop doing that, and trust far more in the process rather than get all anxious about what the process might be like.

LEE

In A Postcard Memoir and Jack and Rochelle, you mention your father’s desire to write. How much did that desire influence you?

SUTIN

I don’t think it influenced me a great deal because as I grew up he did not manifest his desire to write. He was already engaged in making a living and supporting a family and it came up very rarely. His desire to write was more closely associated to journalistic writing than mine was—I did some journalism along the way but I was never that drawn to it. I can’t say it was a huge influence other than sort of a recognition that life’s circumstances had impelled him away from writing and that I wished to remain certain that life’s circumstances did not do the same to me. But his life was very different than mine—far different pressures than mine.

O’GRADY

The pieces in A Postcard Memoir are mostly short, under a few hundred words. Do you work in the longer-form essay or memoir?

SUTIN

Oddly enough, I don’t do that much in the way of essays. Over the years I’ve published book reviews and essays here and there, but I tend to be oriented towards books. My longer-form essays have been biographies, and I’ve just completed a history of relations between Buddhism and the West from roughly 500 BCE to the present day. When I wish to go long, I go very long. Right now I’m working on a novel, in the form of a series of interconnected short forms. I am drawn to shorter forms in creative writing, drawn to trying to write a prose that blurs the distinctions between poetry and prose. But I also feel that my own natural inclination when telling stories or recalling memoir is to focus on distinct, vivid scenes rather than lacing in a great deal of connective tissue which doesn’t seem—at least in my case—to be the essence of my narrative. And I suppose to some extent—I don’t know if I was directly influenced by it but I agree strongly with it—the preface to Jorge Luis Borges’s Ficciones—I wish I could quote him verbatim; I can’t—where he talks about the possibility for writers to get to the heart, the essence, of a situation without the four- or five-hundred-page novel that seems to explore a situation. It is getting to the heart of a situation, and yet having sufficient depth so it isn’t a skimming, that is my aesthetic, that’s guiding me in my writing. So I’m very drawn to short forms.

On the other hand, when I work in other kinds of nonfiction—biography or history—I tend to go more in the direction of exhaustive exploration in the writing, so there’s kind of a systole-diastole in my aesthetic. In certain nonfiction forms, I just write and write and write, and hundreds of pages, even thousands, are fine, at least in draft. Whereas, for something like A Postcard Memoir, I was concerned with having very precise, distilled pieces that conveyed a great deal.

LEE

In A Postcard Memoir you bend a lot of rules. Do you find the conventions of literary nonfiction to be constraining?

SUTIN

Well, not to be naïve or self-effacing, but I’m not sure which rules I bend. I’m saying, frankly, that my goal was not so much to bend rules. My sense in wanting to write this memoir was not, is not, that my life is interesting as a series of consecutive events—I did this, and then I did this, and then I did this, and then I did this. That was not interesting to me, and hence I concluded it would not be interesting to my readers. The other thing I concluded was that my life, to the extent that it had meaning in a memoir context, was largely a series of what you might call inner realizations and emotional states, rather than great events. Unlike my parents in Jack and Rochelle, which is very much a historical memoir concerned with events, time, place, my memoir is not. My memoir is very much an exploration, you might say, of consciousness, emotion, realization, development. So in that sense I guess if there were any tradition of creative nonfiction that I felt that I was bending, I do often feel in reading memoir as though the inner life of the writer or the characters of the memoir are scantily portrayed in comparison to external events upon which the writer may reflect for a time. I wanted to write a memoir that was directed toward inner experience because that was what I had to offer. So in that sense I was aware that I was writing a relatively eventless memoir. There is no great scene in it where X happens and the reader goes, “Oh, my gosh! Really?” At least not to my knowledge. But then again, maybe that was fortunate in terms of my life.

LEE

It seems A Postcard Memoir follows a loose chronological order. If it were roughly broken into thirds, which it isn’t, it seems like the first third, before you went to college, involved more narrative; in the middle portion, kind of the college, post-college years, it seemed to have more engagement with your interiority; and again, after you got married and became a parent, it seemed to kind of pull the two together with a little more narrative. The first third and the last third seemed to involve more family. How does family interact with writing?

SUTIN

I have never thought of my memoir as divided into thirds, but, as you mention it, I can’t say that you’re wrong. I get what you’re saying. It wasn’t part of my conscious methodology but I think it’s a good point and I would say this: you might say that the early years of my life and the later years of my life and the present are certainly far more concerned with living within a family context and the attempt to make sense of one’s own evolution coupled with the demands, the heartache and the passions involved in being, to use the old Buddhist and Hindu term, a “householder.” In the middle years of my life I think I was engaged in an escape from family and social structures altogether, as I was in the midst of trying to discover myself as a writer. And particularly those years of my life when I was redefining myself in that sense, I was engaged in a great deal of inner reflection, doubt, uncertainty. My own identity seemed blurry to me, and that may account for the more introspective, fantastical, psychological orientation of the middle section of the book.

If your question also refers to the process of writing while living within family, I think for many writers there seems to be kind of a dissonance there. They wish to be engaged in family and yet feel that the demands of, let’s say, marriage or parenting or maintaining a household, are detrimental to their writing. I don’t feel that. As a matter of fact I feel quite inspired by the circumstances of family life now to work even harder as a writer, and I love the admixture of working alone in my office for several hours at a stretch and then popping back upstairs and rejoining this social entity which is family. That immersion into solitude and then re-emergence into family is a lovely thing to have in my life.

O’GRADY

Was that ever a problem for you, something you had to work at?

SUTIN

Yes, very much. Given that I was raised in a family where there were parents whose love for me was clear but whose emotional needs were also very strong, I think there was a middle time in my life where I simply needed to be on my own and find out who I was. It took me years of effort to find out that I could write and respect who I was, as opposed to write and pretend to be someone else.

LEE

I’m curious about that. Your parents’ story is very different from your own. Historically, it’s very important; there’s a lot of emotion, a lot of difficult, horrible experiences. You wrote their story before you wrote your own memoir. Did the shadow of the bigness of that intimidate you in writing your own memoir?

SUTIN

No. When I teach memoir, I try not to be self-referential, but once in a while people ask the question, “Well, what is creative nonfiction and is that an oxymoron? If it’s creative and it’s nonfiction, what’s going on?” You’ve heard these paradoxes and dilemmas about the genre. What I try to tell people is there are many different types of memoir just as there are many different types of visual portraiture. My parents’ memoir, in which I served the function, essentially, of a documentary filmmaker, sort of taking their words, giving them the native English they didn’t have, and arranging the narrative, was very much a historical memoir in the sense that I wanted it to stand as history, as fact, as events that could be trusted and believed as such. I’ve been gratified to see that historians have quoted the book and that it’s formed part of the teaching materials of the United States Holocaust Museum. So that’s all very good. In that sense, the type of memoir I produced about my parents was very much like an official portrait you might see hanging in a capitol building or the like, where the goal of the portrait is to portray something of the actual person, exactly how they looked, how they dressed, the context of their public lives.

In the case of A Postcard Memoir, as I’ve indicated, the portrayal of events was not the heart of it. Nobody’s going to read A Postcard Memoir to find out where I went to school or what I did after school. Presum- ably they’ll be reading it for other reasons pertaining to style, emotional portrayal, artistic portrayal and the like. I was released from the bonds of facticity. I could employ fantasy; I could employ dreams, reverie, contradictory emotional states and the like with complete freedom because my life, blessedly, has no historical significance. In that sense my own memoir is much more like an expressionist painting or a cubist painting, where the goal is not that kind of precise rendering of what this person looked like, but rather trying to convey the essence of a life by whatever artistic means you feel are necessary. When you look at a German expressionist painting and you see a purple stripe drawn across a forehead or a cheek, you don’t conclude that the person actually had that purple stripe. You conclude that there is an emotional or aesthetic aim involved. There are many different types of memoir. I didn’t feel any shadow from the memoirs on my parents. I actually felt a sense of relief and freedom, quite honestly.

O’GRADY

You did the biographies of Phillip K. Dick and Aleister Crowley.

What was it that turned you on to them?

SUTIN

I tend to write books without knowing why I’m writing them, and that seems to be a comfortable place for me as a writer. I don’t begin with a lot of preconceptions or goals. I just begin with a sense of, “Wow, this really interests me, I want to do it.” But looking back I can see that what attracted me both to Phillip K. Dick and Aleister Crowley was that both of them worked in despised genres: science fiction, which, at least among literary folks, is still considered trash, and what you might call the Western esoteric tradition or, more brutally, the occult, which is even trashier than science fiction in the minds of most educated people. But both Phillip K. Dick and Aleister Crowley are absolutely brilliant writers, in very different ways.

O’GRADY

In a craft sense?

SUTIN

Crowley very much in a craft sense. He was a marvelous stylist and a very fine writer by the most traditional standards of style. Phillip K. Dick wrote his books at white heat, very quickly, to make a living. I don’t know that most of his books stand up as things of purely stylistic beauty, but in terms of imaginative and visionary quality they’re as fine as any novels an American has produced in the last few decades. Both Dick and Crowley had a fascination with spiritual and philosophical issues and sought to understand the universe, see it whole, explain it whole—which is impossible, in my view—and yet both of them were passionate about trying to do so. I do not myself seek to do so but I am fascinated by people who do. So really, then, they’re like siblings in my head. I had this sort of rescuing complex, thinking that if I wrote insightful biographies of them they would be revalued and seen as worthy of serious consideration. Now, I think that has happened with Phillip K. Dick. It’s not solely, or even mainly, because of my biography, but from the time I worked on that biography to the present day, fifteen years later, I think his reputation and esteem has quadrupled, if I may make up a pointless and inaccurate statistic. Aleister Crowley is still where I found him in a despised genre, but I would simply say to listeners and readers of this interview, particularly to writers, that if they want to read a book that reveals an intersection between creative nonfiction, poetry, and metaphysical speculation, The Book of Lies by Aleister Crowley is a damn good book. And Magic in Theory and Practice is a brilliant examination of human psychology, philosophy, and the use of the mind for creative endeavors.

LEE

In your writings, you often bring up religion—Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity. Maybe you could talk some about the intersection between religion and writing.

SUTIN

It’s very difficult, to my taste, anyway, to discuss spiritual issues in writing. I’m not a formal religionist of any kind, and yet the questions that religion asks are very important and I would imagine that most people, whether they are religious or not, ask the same sorts of questions as they go through their lives. I am fascinated by the types of questions that are raised in religious contexts, and yet I’m unsatisfied with the solutions that any religion has propounded. So I am amongst those writers who draw from time to time from spiritual traditions and sometimes play with them and distort them deliberately without accepting any one of them as the absolute truth that they wish to be. To me, it seems that one of the things that writing can do is carve out a reality of spiritual explorations outside the confines of religion while not ignoring the religious history of humankind. That’s, I think, where I place myself: that I get to ask spiritual questions and even occasionally hint at spiritual nostrums of my own without accepting any dogma or doctrine whatsoever. So it’s really a fascination with the questions rather than an acceptance of any doctrine.

I suppose I should make clear that even though I have just completed a history of relations between Buddhism and the West, and I’m deeply drawn to Buddhist texts and I actually read them for enjoyment, I would be loathe to call myself a Buddhist or an “-ist” of any sort. But asking spiritual questions is part of what interests me about writing. And even as I say that, the word “spiritual” has so many layers of affectation and sugarcoatedness to it that I wish there were another word that could be used as a shorthand for what I’m talking about, but I’ve searched around for it and I haven’t found it.

LEE

Do you find as you’re examining these questions that the religious stereotypes or the conclusions that are already there get in your way?

SUTIN

They used to. Part of what happens in my writing—I’m not sure if it comes out in the actual contact but in the process of it—is liberating myself as best I can from the preconceptions, stereotypes, dogmatic-truth claims that I grew up with from the Jewish and Christian traditions. One of the most exciting things to me about writing is the feeling that writers can ask questions and be true to their own experience without needing to adhere or kowtow to any doctrine whatsoever. But I think it’s difficult to grow up in the world as we now know it and be utterly blank in terms of knowledge of what religions have had to say, or, in my case, to avoid some fascination with what religions have had to say. So, sometimes I use it as material, but I use it as material in the same way that I might use an embarrassing experience at a high school dance as material—it’s all the same sort of material.

LEE

In Jack and Rochelle, your father admits that he doesn’t have the desire to ever return to Poland. Do you have that desire yourself? Have you been to Poland?

SUTIN

No, I have not been to Poland. I don’t have the desire, and the reason is really the same as that of my parents: nothing, essentially, is left of the world in which they lived. The people were killed, for the most part. If they weren’t killed, they left Poland after the war. The buildings, the towns that my parents grew up in were largely decimated by the war. So there’s nothing for me to go back and look at. I grew up being imbued so strongly by the stories my parents told. The reality of that is sufficiently within me. I think going back to Poland would be hunting for something that no longer existed; it would be, at best, a hope of coming upon some archive with perhaps a few photographs. But if I want archives or photographs, I can go to New York. There are archives and photographs there.

What happened in Poland was so ghastly—what happened in Europe during the Holocaust was so ghastly—that my desire to go see it, at least for myself, I’d compare to, let’s say, a woman who had been raped wanting to go back to the scene of her rape. Perhaps some would, perhaps some wouldn’t. I’m in the second category. It’s not any hatred of Poland, per se; there’s just nothing there for me to go back to.

LEE

Do you find that, as a child of Holocaust survivors, when you write, the awareness of the horrible side of humanity separates you from people who have a hard time conceiving of that?

SUTIN

Yes. And when I say it separates me, there’s a lot of misery in the world and I don’t wish to claim a lion’s share of it, or even my parents’ share. The Holocaust was horrible but there are many other horrible events in history. Let’s make it clear that I think many people are very fully aware of the more unfortunate aspects of human nature. But it certainly separates me from people who have a sort of blithe optimism of human nature. I remember a Crosby, Stills and Nash song that came out when I was in college—“Teach Your Children Well,” I think is the name of the song—but it was this very optimistic song that proclaimed if we could just teach everybody peace, love, and understanding what a wonderful world it would be. I remember listening to it back then and thinking, “This is a beautiful song. And it’s complete crap.” And I would say I felt a sense of separation at that time and I continue to feel sometimes a sense of separation from people who are blithely cheery about human endeavors, human ambitions, human aspirations as though we are not capable of a great deal of good and a great deal of evil. I’m always aware that history is difficult and heartbreaking, with a great deal of suffering, and I expect it to remain so and that does definitely inform my vision, yes. But that doesn’t make me a misanthrope. I still feel there is something good in human nature. But there is also something very foul in human nature, and I don’t suppose it’s news to anyone that each one of us has to struggle with that. I’m not a utopianist by any stretch of the imagination. I don’t believe in a progress of humanity to a better and better future. I think we will have peaks and valleys and struggles and misery and perhaps some light as well.

O’GRADY

Would you talk about your current project?

SUTIN

I’m working on a novel composed of interlocking shorts, something in the style of A Postcard Memoir, and the working title of it is When to Go into the Water. It is an entirely fictional account of a strange man growing up in the east of France who leaves his family and his culture behind and travels around the world and experiences a great many things. Oddly enough many of them have to do with water and when to go into it. I think I’ve whetted the future reader’s appetite enough by saying that much. I’m interested in working in fictional forms more and more since I don’t know that I have another memoir to write.

O’GRADY

What is the time period of the novel?

SUTIN

Late 19th century through early 20th century, far removed from our reality.

O’GRADY

Have you thought about working more in biography?

SUTIN

No, I will never do biography again. I’m announcing that to the world. And the reason for that is, as I was working on the Crowley biography, the second one, I thought, “Why on earth have I done the same thing twice?” Having written two biographies I can say that, even though I think biographies are interesting books and worth writing and all that, for me they’re extraordinarily confining. That is because there’s sort of this set of iron manacles—you extend your arm, and then you are handcuffed to your subject and you have to cover their entire life. As a biographer you don’t get to say, “You know, these ten years here, not a whole lot happened that was really that interesting. I think I’ll just fast-forward.” You have to talk about those damn ten years, unless you’re going to write a very kind of episodic form of biography which doesn’t fulfill most readers’ desires. I ultimately found biography to be an extraordinarily restrictive genre. The first time through it, with Philip K. Dick, I had a great deal of fun, but the second time through, with Aleister Crowley, I thought, “I’m doing the same damn thing over again. I’m stuck with this guy’s life and I have to talk about every year of it.” That doesn’t mean that I think I wrote a bad book, just that I was compelled to retain a certain form. No, I will never, ever go back to it.

Now, I’ve just completed a history and that was way more fun because, since I was dealing with 2,500 years of relations between Buddhism and the West, and no one could possibly expect me to cover every day and every month of 2,500 years, there was a great deal of freedom in deciding upon what I felt was important. So I would say that, for me, that’s a far more appealing genre. I should add that I find history to be as creative as other forms of creative nonfiction. I think it’s a shame that writers of creative nonfiction sometimes feel that memoir is it, or memoir and travel books are it, and the fact is you can write about anything as a nonfiction writer and make it creative if you bring your voice and vision to it.

O’GRADY

You wrote the history as a creative writer and not as an historian?

SUTIN

Well, since I don’t have a Ph.D. in history, I suppose I’m a creative writer. I’m a megalomaniac in terms of what writers can do in the field of nonfiction. If I have one thing to say to the nonfiction writers of the world, it’s that you can write about anything you want if you bring your intellect and your passion to it. I think one of the things that writers can do better than historians, for the most part, is write. They know how to create a narrative with interest and depth, they know how to discern between significant material, and because of their training, which is different from that of the typical academic historian, they have a greater freedom of allowing their voice to come in and interpret. All those things seem to me to be strengths in historical narrative. So I would claim that I’ve written a work of history, but I have written it as a highly informed, fanatically researching creative writer. And I feel that I can write about anything I care to. Which doesn’t mean I’m excused from knowing the facts, just that I can combine my writing skills with the facts and produce a book that I think has a creative voice. Creative nonfiction as a genre has restricted itself to some degree in recent years. If you go back to, say, the beginning of the century, it was frequently the case that writers would write history, biography, essays, memoir, travel, and poetry. That’s what a man or a woman of letters was—someone who wrote about subjects that interested them. We seem to have narrower categories now—poets can write poetry and maybe some essays on the side, and fiction writers, of course, can write novels or short stories. Creative nonfiction writ- ers can write memoir, travel, or essays of a certain type. But I’m rather fond of seizing the entire world as subject matter and any type of book as potential subject. So that’s my outlook and I’ve managed to deceive enough people to enable me to go on doing it.

LEE

You got your law degree at Harvard. Are you still practicing?

SUTIN

I’ve not practiced law in over twenty years.

LEE

Why did you go to law school?

SUTIN

Well, I went to law school because, having grown up in a Holocaust family, where a great deal of fear and anxiety about the nature of the world was conveyed to me, law seemed to be a security blanket. The world is a frightening place, it’s difficult to survive in it. How writers make a living, when I was in my teens and early twenties, I had no clue. And the idea of an MFA track, frankly, had never crossed my mind. It was not a prominent option at the time. I was frightened of the world and I thought, “Well, I’m smart, I can deal with words, I can be a lawyer.” But I found very quickly that I was not a lawyer in any way, shape, or form, that there was nothing about the profession that satisfied my heart and soul. And after a few years of making myself miserable as a lawyer, I decided that I’d better do that which I could do rather than that which I felt I ought to do. And so I quit. I suppose legal training was useful to some degree in my writing, at least in recognizing intricacies of argument, intricacies of point of view, how to parse things so that everything can be debated, refuted, looked at from different angles. But I simply was a very unhappy law student and lawyer. And I went to law school out of fear of the world. That’s all it was.

LEE

A Postcard Memoir reminded me of some of William Blake’s work, the way the visual representation and the literature had a conversation.

SUTIN

Thank you, thank you, thank you.

LEE

Was he one of your literary influences?

SUTIN

Oh, definitely. William Blake is—gosh, how do I put this without sounding ridiculous?—one of the most stunning, remarkable, gifted, and stirring writers in the history of human civilizations. If in A Post- card Memoir, I tiptoe in the direction of Blake just a bit, only in terms of word and image informing each other, it was because if there’s one writer in the history of the world I envy it is William Blake, because he was able to create images of such surpassing power and beauty to go with his text, and I don’t have that skill, so I was forced to paw through a postcard collection to find my visual components. Oh, if only I could create the images Blake did. But yes, the interplay between text and image is a remarkable component of Blake, and I would urge people who know the poetry of Blake only as text to try to find—these days it’s not so hard—reproductions of Blake’s art along with the poems. So, yes, he was definitely an inspiration to me in that regard. I have always, always been fascinated by the interplay of image and text. I have felt that writers can do that and don’t do it enough. And I did it the way I could.

LEE

Who were some of your other literary influences?

SUTIN

In that sort of formative era of teens and twenties, the works of Henry Miller and Isaac Bashevis Singer and John Cowper Powys, the English novelist who is not very well known in America but is still quite well regarded in England, those three were powerful voices. And the French writer Blaise Cendrars was another writer who opened things up for me. Walt Whitman is someone to whom I still turn with a great deal of reverence and joy. Obviously Philip K. Dick has some appeal to me since I wrote a book about him. Way back in the mid-eighties, and I’m a little proud of this because the film American Splendor has just come out and now he’s much more well known, but I actually bought issue two of American Splendor on the newsstands and was reading Harvey Pekar way back when, and I did an interview with him, speaking of interviews, that was published in what was then the Hungry Mind Review in 1990. I remember talking with him about the fact that he could not draw so he did these sort of stick-figure comic-book storyboards as he would call them and then got artists to work with him, which I think to some extent I did in A Postcard Memoir—using dead, anonymous postcard photographers as my artists. The example of Harvey Pekar was always very fascinating to me, someone who took these sort of non-exceptional facts of life and turned them into stories with meaning. I don’t think Harvey Pekar and I write alike or have the same sensibility but his basic approach to the possibilities of word and image is something that I feel some kinship with. These days I read a great deal of poetry. There’s a contemporary American poet working today, Mary Ruefle, who I think is astonishing. I loved Homer’s Odyssey. How’s that? I had a crush on Virginia Woolf in college. I had her picture up on my wall, a little postcard picture. I thought the young Virginia Woolf was just hot. I don’t think we would have had much of a future. But, my gosh, I’ve been swimming in books all my life, so it’s a very difficult question to answer.

O’GRADY

Some people suggest that there’s sort of a divide between West Coast and East Coast writers in their approach and themes. Do you agree with that, and, if so, do you think there’s also a Midwestern aesthetic, and would you fall into that category?

SUTIN

I think sometimes there is a noticeable divide between East and West, and sometimes not. It depends on the writer. There are many writers—don’t ask me to name names—but I know there are many prose writers living on the West Coast who are seriously regarded in the East and the like. I think it shows up more in poetry, where there seem to be East Coast schools and West Coast schools of poetry, sort of New Yorker magazine schools and more free, open schools. If there is a Midwestern aesthetic, it means nothing to me. I guess readers would have to judge whether I fall into it or not. I certainly am affected by the places that I am, and I’m very particular about where I wish to be, but I’ve never felt that I’ve participated in or took on a specific Midwestern aesthetic. And to the extent that there are East Coast and West Coast differences, I tend to think they are more in terms of clashes of ambition and job searches and control of publications than actual differences in the writing. So maybe my fundamental answer to the question is those sorts of distinctions don’t mean a great deal to me as a reader or as a writer. I don’t deny that they do mean something to other people, but for me I don’t care that much where a writer is from, and frankly if I didn’t have the little dust-jacket bio of a writer and you asked me, “Is this person an East or West Coast writer or a Midwest writer?” I bet I’d be wrong eight out of ten times. But there’s a lot of Midwestern writers who are experimental, edgy, strange people. Take the Twin Cities, for example. I guess they have this sort of candy-coated Midwest flyover image for the rest of the world, but just look at the music that has come out of Minneapolis. You wouldn’t expect Hüsker Dü, Soul Asylum, the Re- placements, and Prince to be coming out of there, and yet they do. Paul Westerberg lives six blocks from me. So is he a Midwestern musician? I don’t know him very well but I doubt he would nod his head yes to that. To me regional labels have more to do with social preconceptions than with the actual impact and realities of writers.

O’GRADY

How would you like to be remembered as a writer?

SUTIN

I would like to be remembered as a writer. How’s that? I’ll settle for being remembered as a writer. As to how, I have no idea. I think most writers would like their books to continue to be read, and I would be content with that. There’s no particular image or label that I crave in that regard. That the books themselves would continue to have life would be sufficient.