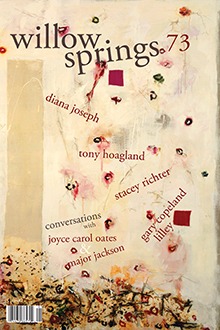

Found in Willow Springs 73

April 13, 2013

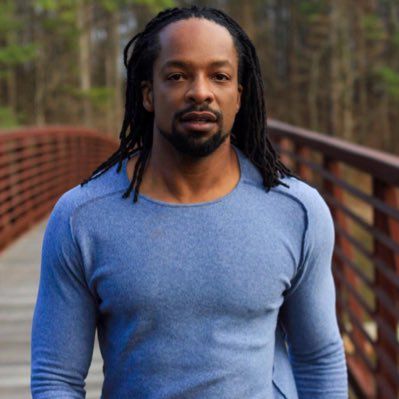

Melissa Huggins, Katrina Stubson, Ben Werner

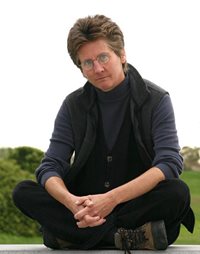

A CONVERSATION WITH JOYCE CAROL OATES

"I believe that art is the highest expression of the human spirit,” Joyce Carol Oates declares in The Faith of a Writer, “I believe that we yearn to transcend the merely finite and ephemeral; to participate in something mysterious and communal called ‘culture.’”

Oates has dedicated herself to life as an artist. She’s produced over a hundred published works, including novels, short stories, essays, poetry, plays, and book reviews. But more impressive than the sheer volume of her work is the empathy required to bring to life such an array of characters. She has inhabited the minds of serial killers and politicians, young mothers and abusive fathers, starlets, famous writers, prisoners, and more. Often her fiction centers on the aftermath of a moment of violence, circling back to that moment repeatedly over the course of a character’s life, delving into the damage, and usually moving toward a kind of redemption—but not always.

Oates grew up in Lockport, New York, and attended a one-room schoolhouse, where she pursued an interest in writing, drawing, and other artistic endeavors from a young age. Upon receiving her first typewriter as a gift from her grandmother at age fourteen, Oates began contributing to her high school newspaper, and wrote stories and novels throughout high school and college. Her novels include them, which won the National Book Award; Blonde, a Pulitzer Prize finalist that imagines the inner life of Marilyn Monroe; The Gravedigger’s Daughter, loosely based on part of her own family history; New York Times bestseller The Falls; and We Were the Mulvaneys, which details the disintegration of a seemingly perfect family. Her nonfiction includes the essay collection On Boxing and a memoir, A Widow’s Story. Noted for being prolific, Oates publishes an average of one to two books per year, in addition to her teaching, reviewing, editing, and other pursuits. “It is sobering to be asked—so often—‘How are you so prolific?’ When I feel so earnestly that I am always behind, and never caught up,” she writes. While she recently announced that she will retire from Princeton after teaching there for over thirty-five years, she plans to continue teaching elsewhere, and 2014 will see the publication of a novel, Carthage, and a story collection, High-Crime Area.

Since 1963, over forty books by Oates have been included on the New York Times list of notable books of the year. Among her many honors are two O. Henry Prizes, the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in Short Fiction, and an M. L. Rosenthal Award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In 2010, President Barack Obama awarded Oates the National Humanities Medal, and in 2012, she was awarded both the Mailer Prize for Lifetime Achievement and the PEN Center USA Award for Lifetime Achievement. We spoke with Ms. Oates during the Get Lit! Festival in Spokane, shortly after the publication of her Gothic novel The Accursed. We discussed, among many topics, the “fantastic risk” of being a writer, feminism in the age of Twitter, and the transcendent nature of art.

Melissa Huggins

Edmund White once said that you seem to dream your way into your fiction, as if you were in a waking trance, and that you imagine other lives so vividly that they must leave you exhausted. Does that seem accurate?

Joyce Carol Oates

While that might be true for some of my writing process, I’ve been writing so long, and with so many different projects, that it’s probably only applicable to some aspects. I’m a professor, I teach literature, and I’ve written a lot of literary criticism and reviews, so there’s a side of me that’s extremely conscious. I was talking about postmodernism last night, and postmodernism is really an attitude, a way of looking at life and literature, where you’re drawing upon different traditions very consciously and choosing to present things in a form, so you’re also a formalist. And that’s different than being in a trance or dreaming. The two might fit together in some way, but in my deepest heart, I’m probably a formalist. I’d love to be given a certain structure for a work of fiction, to see if I could put content in it. There’s something about form and structure that excites me—maybe the way the sonneteers were in the Renaissance, writing sonnets, writing them brilliantly, and competing with one another. They were writing works of great art, yet within a form.

Huggins

Was that part of your goal in writing The Accursed? You had a structure, and you wanted to fill it in?

Oates

No, I didn’t have a structure in mind; it was more like an idea, writing in a certain genre or a certain place. I wanted to write a number of long, quasi-historical novels, and for that you need a broad canvas. It’s not the kind of intense insular writing you find in Henry James, narrow and deep, with maybe two or three characters. With this kind of writing, you want characters who are somewhat contrasting, maybe of different social levels, different personality types, and when they come together, narratives derive from these characters meeting. With a novel like The Accursed there are many quasi-historical characters. So if I’m writing about Woodrow Wilson, I’m trying to imagine what it would be like to see him in 1905 and not be overwhelmed by his fame or authority, but to see him from the perspective of somebody who might not think he was extraordinary—because they were both living at that time. What would a contemporary think? Some didn’t think much of him, so the novel accommodates that. The novel’s character driven, but the form is gothic horror. I knew there would be a curse and manifestations of the curse, which increase in horror, and then there’s the pursuit of the mystery, and hints to the reader about what the mystery is—but not too openly. It’s not exactly a structure, but more an intuitive sense of what you’re doing, and you know the last chapter will explain it, because it’s a genre novel. It’s not a literary novel in the sense that it’s irresolute, ambiguous. With a genre novel, the ending is like a light thrown back on everything, and if you read it a second time, you see how it fits together. That’s a classic mystery form. When a mystery is done correctly, you read it a second time and it all makes sense. But the first time, you’re mystified. Sometimes with a novel, people say, “Oh, this is predictable,” because they’ve seen it before. Or you sit down to a movie and after twenty minutes you see where it’s going, and you’re not surprised, because the form has become formulaic. But you can also make a form feel new—you can have surprises, and you can do reverse things. For instance, I like to have a character who you see from the outside as superficial, but who gets deeper as the novel goes on, maybe veering in a new direction and meeting somebody, and because of meeting somebody, changing.

Katrina Stubson

Is your research process for historically based fiction different from your research process for nonfiction?

Oates

I’m not a historian, and I don’t really write historical novels. The Accursed was more of an experiment. I did write a novel you could call historical, Blonde, about Norma Jean Baker, who became Marilyn Monroe. I saw a picture of her when she was about sixteen, a high school girl, and she didn’t have blond hair and she didn’t look much like Marilyn Monroe, just a tiny bit, and I thought, How interesting to go back to whenever that was, and to write about her as that girl. I went back further—to write about her when she was just a child with her mother. I did a little research into the Hollywood of that time, because they were living in Los Angeles and her mother worked in one of the studios, and I did some research into what movies they were seeing and what the studios were making and where they lived, which was Venice Beach. I was going to end the novel when she becomes a starlet and gets her name, Marilyn Monroe. But when I got to that point in the novel, about 180 pages or so, I thought, Well, I can’t stop now. I started doing more research. I saw all of her movies, ending with The Misfits, which came out when she was about thirty-five. I could see this young actress maturing—she was an excellent actress—and I could see her getting older and becoming more like a cliché. In The Misfits, her last movie, she’d become the Marilyn Monroe stereotype. She’d started out as an individual, and then she got deeper and deeper, until finally she would have to live out the stereotype—that they’d made her up, that she was so into her clothing—and I think she probably felt, perhaps unconsciously, that there was no more life for her, that she would have to keep doing that Kewpie doll thing for the rest of her life, and so she committed suicide. That was a different kind of research, generated during the writing process, not before. It was research generated by the act of writing. With The Accursed, I had fun looking for ironies and surprises and comical things in the lives of people like Woodrow Wilson and Grover Cleveland and Teddy Roosevelt, because they’re always presented as these males who’ve achieved so much as presidents. But we can also present them differently, as human beings. Woodrow Wilson was a man who rode a bicycle around his town because he couldn’t afford a car, and the well-to-do ladies were kind of snobbish, like, “Oh, he’s riding a bicycle.” That’s a whole attitude toward a president that most people don’t have, seeing him from the point of view of the townspeople.

Ben Werner

When you’re fictionalizing historical characters, is the approach different than when you’re writing purely fictional characters?

Oates

Woodrow Wilson had many, many letters and a lot of words he wrote that I could copy down, especially the foolish things he said, and some of them lofty things, but everything he said kind of annoyed me. For example, this famous speech he made, “Princeton in the Nation’s Service,” was about how Princeton is great, and because it’s so great everybody has to be great, even the students have to be great. There’s so much pride and vanity. What about other universities? Maybe they’re great, too. It was this tiny vision he had, and there was something about him I found annoying. So I guess I would look at those things, whereas if I were writing him as purely fictional, I wouldn’t put so many of those details in, because people would say, “Oh, you’re exaggerating.” But when you go to history, and see the insane things that, say, Hitler said, you probably wouldn’t make them up, because they’d seem over the top. White supremacists provide us with wonderful copy because they say the most asinine things. You couldn’t write poetry as bad as the poetry they loved.

Stubson

You write that you were in love with boxing from the moment you went to fights with your dad. Was On Boxing a book you’d thought about doing for a long time?

Oates

When I was a girl, my father did take me to fights, and I was interested at a young age in this very masculine sport. I wouldn’t say I was in love with it. I was a girl at ten or eleven with my father in a masculine environment, but I didn’t have any thoughts about it. I wasn’t a feminist yet. We would watch boxing matches on television, which were on every week, and there were great boxers at that time. I was aware of them, but I wasn’t a student of them. Many years later, I was writing a quasi-historical novel called You Must Remember This, in which the character’s a boxer in the 1950's, a great era for boxing. I was writing about the Red Scare, Senator McCarthy, people informing on each other, loyalty oaths, stuff like that. I did some research, looking at films of boxing in the 50's. One day the phone rang and it was the editor of The New York Times Magazine, Harvey Shapiro, who was always asking me to write something, and he said, “What are you working on?”

I said, “Well, I’m working on a novel, so I don’t think it would be of interest to you,” and he said, “What’s the novel about?” and I told him. He said, “You know, Father’s Day is coming up. Why don’t you write an essay about going to the fights with your father?” “Oh, I can’t possibly do that,” I said, and I hung up. Then I thought, Well, if I’m a feminist I better say yes, because a feminist is supposed to take challenges. So I called back and said, “Okay, I’ll try. I’ll send you something.” I started writing this essay, and it got long and complicated. I was going back to the ancient Greek warriors and all this history and it was this and that, and I was kind of devastated by how hard it was to do because it was for The New York Times Magazine. I knew about a million people would read it, and I was self-conscious. There’s a certain solace in writing fiction—you almost think nobody’s going to read it. You feel protected. But when you do this kind of journalism, especially in the New York Times, everybody’s going to read it, and a lot of the people who are going to read it are people who don’t know you, they don’t like you, they could be contemptuous. I got paralyzed. I was anxious and depressed and writing more and more, and none of it was very good. I told my husband, “Well, I completely failed, I’m giving up.” And I was devastated. But the next morning I thought, I’ll write about failure. Because most boxers fail, and that’s the secret of boxing, to take this terrible punishment. Even the champions fail eventually. So the first thing I wrote was about a terrible boxing match I’d gone to at Madison Square Garden, and that’s the beginning of the book.

If I hadn’t had the call from Harvey Shapiro, I would never have written any of this. I couldn’t get it together until I felt that it completely failed. But that’s the secret of boxing and maybe a lot of sports: athletes have to endure failure. People look at the champions and think, Oh, look at this wonderful champion, with no idea of what the pyramid is like, and how at the bottom of the pyramid are broken, defeated, injured people, whose lives have been devastated by the sport, especially in the past. Now there are doctors who are more vigilant. But in the past, a young man could sustain an injury in the ring, very young, twenty-two years old or so, hemorrhage a week later and die, and nobody would care. My father had a boxer friend who committed suicide—he had been badly over-matched and defeated in the ring. At the time I didn’t think anything of it, but as an adult looking back, I thought, Of course he committed suicide.

And so I saw that line there. That’s the secret of the book. If I didn’t have that, I wouldn’t have written On Boxing. The essay came out in the New York Times on Father’s Day, and it was successful as an essay— I started getting telephone calls, including from boxers. A photographer wrote to me and said, “I’d like to do a book on boxing. I’ll do the photographs and you can do the text.” That was John Reiner, who became a friend, and they were just wonderful photographs. I thought it would be a book with big photographs and I would do the text. Then, as time went on, the editor wanted me to write more, and the photographs got smaller, which I was sorry about because they’re so good. The book has been reprinted a number of times, and each time I’ve added more. I have a lot about Ali and Tyson, and I have some book reviews. I could maybe add something about women’s boxing some time. The original text came out when Mike Tyson was just ascending—he may have already had his title. I got a call from Life magazine, saying, “Will you cover Trevor Berbick defending his title against this young boxer?” I said, “I don’t think I could do that,” because I’d never covered anything like a sports event—that’s a whole other kind of writing. But I called back and said, “Okay, I’ll try it,” and they sent me to Las Vegas. I was sitting next to Bert Sugar, who’s this legendary boxing writer, and I’m surrounded by these guys with their cigars, and I’m sitting there like I don’t know what I’m doing—because you can read about boxing and see pictures and films, but when you’re right there, you can’t even see their hands, they’re so fast. So Bert Sugar, this guy with his cigar and his fedora, he took pity on me—there’s smoke all around—and he said, “Ah, well, I could tell you some hints,” and I said, “I would really appreciate it, Bert; I don’t know what I’m doing.” He said, “Well, the first thing you gotta do is, you get a tape of the fight. And after the fight, up in your room, you watch the tape. And you watch it and watch it and see what really happened.” That’s the most important thing they told me. That’s what sports writers do if they can, because otherwise you hardly know what you’re seeing. So that’s what I did. I wrote a long piece on Tyson for Life magazine, which got a lot of attention, and then I did a few other pieces. That’s the long story about On Boxing. It was a lot of fun and I wish I could find another subject that would be so exciting and interesting to me.

Huggins

You light up when you talk about it.

Oates

It’s because of the boxers. Their characters and their personalities are amazing. Each boxer is an interesting person, plus their trainers, sometimes their managers. Each fight, each classic fight is kind of astonishing. Some of them seem almost like fairy tales. The classic fights are extraordinary. You have the great Cassius Clay, Muhammad Ali, and he’s almost like a dancer, so mercurial and fantastic. He transformed the sport. The other boxers who come afterward are probably all in some relationship to him—there’s no boxer that’s not aware of him, and whether they know it or not, they exist in relation to him, especially heavyweights. Tyson was quite a good boxer, as well as a good fighter. People wonder how he would have done against Muhammad Ali. It’s these personalities.

Stubson

In On Boxing, you relate boxing to writing in various ways. In particular, you wrote about Rocky Marciano and his monastic rituals leading up to a fight. I’ve read that you relate to those rituals as a writer. Could you talk about how important ritual is to you?

Oates

People do make analogs between boxing and writing. I don’t think the boxers share in it as much as writers imagine. But boxing is collaborative. When you see a boxer, invisibly around him are his trainer and a lot of other people. There almost isn’t a boxer by himself. Ali had a great trainer, Angelo Dundee. Without Dundee, we wouldn’t have Muhammad Ali. Cassius Clay nearly lost his first fight against Sonny Liston. He was going to quit. He was actually made to go back up and finish the fight. Without that trainer, you never would have heard of Ali. With a writer, it might be true sometimes that there’s a mentor or somebody helping, but I think writers are often much more alone. Boxers are more like actors. People see an actor onstage or in a movie, and he’s not alone. There’s a director who’s telling him everything. Basically, they’re sort of material that directors are using. But I think writers are much more alone, and adrift, and unmoored. Imagination is like a river going along. The gifted athlete is someone that somebody has taken and invested money in, given him a regimen, even a diet, controlled his career, set him up with competition. He’s much more guided than a writer. There’s also the idea of taking punishment, and delaying gratification. If you’re a young boxer, you have to know how to take pain, and if you’re a young writer, I guess it helps if you know how to take pain. You can work on something for months or even years, not being sure it will ever be published. That’s a big risk. That’s a fantastic risk. To think that you can invest months of your life in something and it might come to nothing? The same is true of a boxer. You can invest so much effort, and the first important fight he could lose. Somebody’s going to lose that fight.

Huggins

As you said earlier, it’s a constant cycle of failure for boxers. You’re going to continue to keep failing, and that seems like somewhat of a parallel with writing. Not in terms of submissions or publications, but the writing itself.

Oates

Writers tend to set their own levels of achievement. We’re all different. Some feel that if you write all through the morning and have two or three pages, that’s all you really need to keep going, and then in the afternoon you can go for a bicycle ride, and the next morning you do the same thing. That’s a nice schedule. But then there are writers who are fanatic, who get neurotic and obsessed with their work. Maybe they would think that wasn’t enough, or they would rip it all up or get drunk. The schedule is not a solace to some people. I know Robert Stone. He’s taken a lot of drugs—this is not a secret, he writes about it. He’s a very gifted writer, but I know there’s a dark, deep, obsessional personality inside him. I can’t imagine what’s going on. David Foster Wallace is a more contemporary example. You know from his writing that his mind is convoluted, sometimes playful. You have to extract from that what it was like to be him. Maybe he could work for eighteen hours and not be happy with anything he did. Maybe he could have a whole manuscript and hate it, and become so trapped that he would commit suicide. Whereas the boxer is more like somebody’s son. The trainers are usually a bit older, sometimes they’re quite elderly, so the boxer is like a grandson. Say you feel depressed: your trainer talks to you, he’s nice to you, he buoys your spirits. I don’t think writers have anything like that. If someone tries to cheer a writer up, they’re just ironic. Writers are somehow so defensive, or too self-conscious.

Stubson

In the fall of 2012, you wrote on Twitter, “Last night at the Norman Mailer Center awards ceremony in New York City, Oliver Stone said beautifully, ‘A serious writer is a rebel.’” Could you elaborate?

Oates

A serious writer is transgressive. A serious writer sets out to write something that maybe disturbs and annoys some people. You’re not going to set out to write a novel that’s bland and makes everyone say, “Oh, yeah, I agree with that.” Nobody wants that response. You want to turn people’s expectations a bit. I know that some people are annoyed or offended because I wrote about Woodrow Wilson in this way that was not acquiescent or admiring, the way you’re supposed to be. It’s like writing about Abraham Lincoln, whom I do actually revere, or George Washington. Why should we revere these men just because we’re told to? Obviously that’s a little bit of a transgressive act. Oliver Stone is in that tradition—many of his movies are controversial—and Norman Mailer was in that tradition, too.

Stubson

I know you’re interested in Twitter. What appeals to you about it? Who do you follow?

Oates

Twitter is interesting because it’s so short. I find that I spend a lot of time reworking a sentence, throwing out punctuation, changing it around so I don’t need a comma. It’s actually very satisfying. I’ve not been involved in Facebook at all. Twitter is so much more verbal, and it’s somewhat more intellectual. I follow some writers, Daniel Mendelsohn, Ayelet Waldman, Dexter Palmer—writers who are friends of mine. Daniel Mendelsohn sometimes tweets in foreign languages, Latin, German, French. It’s a new art form, I think. I follow Steve Martin, who’s a friend of mine. Steve will tweet infrequently, but then he might tweet eight times in a row. He’s very surreal, smart and funny. Then I follow the Tweet of God. He tweets about five times a day, and he’s always good. He’s so irreverent, but actually really smart—sort of a wise guy, almost like Mark Twain. He’s a former comedy writer for Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. The person who does Twitter, line by line, is Emily Dickinson. Her little observations, some of her poems, her letters, they’re all very elliptical and short. You have to read them several times to get any meaning out of them. Then there are people, like, say, William Faulkner, who could never do Twitter. Hemingway could do Twitter. There’s also a lot of stuff about women, a whole women’s community. There are usually two or three articles that are being read and discussed, like the one from The Nation, about a woman being treated so badly as a writer. Post-feminist, post-something. When I read it, I thought it was very powerful. Then I read critiques of it. She was sort of fabricating it. So there’s a whole issue, and they come and go maybe once a week, these articles. But the big conversation on Twitter is, Are women treated differently as writers, like second-class citizens? There’s a lot of evidence that they are, that they’re not reviewed and so forth. That’s one of the things about Twitter that’s kind of exciting.

Huggins

In terms of Twitter being a breeding ground for conversations about women writers, there is always discussion when the annual VIDA statistics come out. Could you talk about that discussion and to what degree it interests you?

Oates

I think it’s an important discussion to keep roiling and bubbling, sort of like women’s rights, generally. With abortion rights, people think a battle’s been won, but actually it hasn’t. It’s a ceaseless struggle even to having voting rights for people; in the South they’re trying to take them away again. Nobody would believe that’s happening. So too with women and literature. Women buy most of the books and do much of the writing, but not all of them are literary writers. With literary writers, it’s more of a rarified and controversial arena, kind of pitiless. People are really mean to one another. I was talking with students yesterday about young adult fiction. That’s an arena of writing where people are made to feel welcome: the reviews aren’t nasty, people are given two or three book contracts. They’re treated differently from literary fiction, which is like a battlefield. People are fighting for review space, and they’re bitter. If they get a bad review, they’re angry. If they don’t get any review, they’re angry. It goes on and on. I feel sort of hypocritical if I say anything, because I’m often asked to review, and I turn down most of the invitations. So I can’t go around saying, “Women don’t review enough,” because people can say, “Well, Joyce, we’ve invited you, but you turned us down.” I probably should do more reviewing. I review for The New York Review of Books, I did something for The Times Literary Supplement recently, and sometimes for The New Yorker. I am a woman writer who is invited to review. At the same time, often I’m given a woman to review. But if I ask for a man, they’ll give me a man. Just left to themselves, I don’t think they’re thinking about it. Four books by women come in: “Oh, send them to Joyce.” A new book by Michael Chabon comes in, they send it to a male reviewer. It’s like a default. I think that debate you mention makes editors think a little more. They think, Well, have I been doing that? And now The New York Times Book Review editor is a woman, but no one remembers that twenty years ago there was a woman book review editor. Nobody seems to know that.

Huggins

It seems shocking that editors would automatically send someone of your stature only female writers to review.

Oates

You never exactly know with reviewing, whether someone has already been approached and declined it. I know at The New York Times Book Review I’ve been asked to review several times, and I’ve had to say no for different reasons. So they go to somebody else, and maybe before me they went to somebody else. You can’t make judgments. I’ve edited some books and special issues of magazines, and I know what it’s like to get work out of people, to have a fair distribution with all kinds of people, and there are some people who just won’t do it. You try getting various people, and they say, “Well, I’ll send you something,” and they never do. So I’m not as quick to criticize editors as people who don’t know what it’s like to be an editor.

Huggins

One result of the discussion following the release of the VIDA statistics was that it motivated some editors to consider the implications of those numbers. For example, the editor of Tin House, Rob Spillman, said that when they started to dig into their own numbers, the slush pile submissions were approximately 50/50 in terms of gender, but when they looked at whether each writer had been rejected before by the magazine, the men were five times more likely to resubmit than the women.

Oates

Oh, they gave up. That’s interesting. I’ve had a number of students at Princeton who were gifted, both men and women. But predominantly it’s the young men who went on to be published. You’ve heard of Jonathan Safran Foer? He had a novel based on his senior thesis. I’ve had quite a few other writers, but most of the ones you’ve heard of are men. Jonathan Ames has been around quite a while; he’s another one who did a senior thesis with me. He worked really hard. After he graduated he wrote to me and said, “I’m lying on the floor of my apartment and I can’t move, and I need for you to help me. I’ve completely broken and I need some help.” I wrote back to him and said, “Jonathan, you’ve graduated. You’ve got to be independent now. I’m not your professor anymore.” Evidently he got up—he’s got a real career—but there were young women in those workshops who were just as good, and I don’t know what happened to them. You can’t really make somebody revise a novel and keep working. I don’t know where they went. When I had a literary magazine with my husband, Raymond Smith, we published a woman who was about sixty, and she was so happy we’d published her. I said, “You’re such a good writer; where did you come from?” She said, “Well, I had a story in Mademoiselle when I was nineteen, and then I sent them another story and they rejected me, and then I stopped writing for forty years.”

Can you believe it? She said, “Well, I just felt so bad, I didn’t write anymore.” Whereas a man would say, “Okay, I’ll send them another story, or I’ll send it to Esquire.” It’s a lot different. I try not to be easily wounded. When I was a young writer, I would have seventeen stories out to the magazines. It was like fishing with seventeen lines: you don’t expect anything much, maybe you get a nibble. If you have one line out that’s too much depending on it, but if you have seventeen. . .

Werner

How has your writing changed over the years?

Oates

Generally speaking, my writing is more driven now by voice than it used to be. When I started writing it was only one voice, and that was my voice, because I didn’t know how to write any other way. Now if I’m going to write a novel—say I write about some young black people in Newark in 1981, which is one of my new fiction pieces I’m working on—I make it driven by their voices and their personalities. It’s more mediated by the subject, whereas in the past the narrative voice was the author’s voice. That’s the biggest change. I really like writing with voices. That, to me, is exciting. With any work of fiction, the prism is the character. If you’re writing an intellectual character, your tone is intellectual, your sentences are a little longer and more subtle. If you’re writing about a young person, the sentences might be more impressionistic and shorter. It’s always exciting to find that voice, which is not a literal voice; it’s sort of poetic, but mediated. To me, that’s the exciting part of writing.

Huggins

That sense of discovery?

Oates

Yeah, you have to work a while to find the ideal voice—not too elevated, not too plain—and adjust it. I was saying yesterday that there are certain ways of writing that are gone now, that people don’t do anymore. Once there was an elevated voice that was for everybody to read; Milton had that voice, and was widely read. Now, nobody really writes in that voice. They’re much more likely to write in a vernacular voice. You know Junot Díaz? He’s completely in the vernacular, but poetic. I’ve taught his stories, and he’s deceptive; you think he’s just talking, but you find metaphors, maybe two or three in a story, and they’re really sharp. It’s an American vernacular idiomatic voice but it’s poetic, and that’s a nice voice; that’s something we really like. Whereas a complicated voice, like David Foster Wallace, I personally didn’t find as engaging as some of his contemporaries. To me, it was too much of a wrought voice, too worked over, with his footnotes and so forth. Too writerly, like he was sculpting or carving out of stone rather than the fluidity of Díaz, which is almost like water running along.

Stubson

I’m curious how you determine your persona or your voice in terms of writing essays or reviews. Was finding your voice outside fiction difficult?

Oates

I’ve been writing a lot of reviews since my early twenties, so you find a writerly voice that’s communicative and not too dense. And if you write for The New York Review of Books, you have a sense of audience, which would be different than a newspaper.

Werner

Do you consider audience in your writing? It sounds like you did when you were starting to write On Boxing.

Oates

Only regarding these journalistic things, not with fiction. You can’t imagine any audience with fiction. But with The New York Review of Books, the essays are always well written, by distinguished people who are experts in their field. They write carefully, and the first paragraphs are always so good. I love the New York Review; I just love to read it. Sometimes I sit and underline the prose of these wonderful writers. So when you’re going to write for them, you take a lot of time and care. But basically it’s not voice, it’s just a little more worked over than it would be for some other magazine.

Huggins

You’ve written and spoken about the transcendent nature of art, and you’ve been quoted as saying, “Life without art to enhance it is just too long.” How does art make life bearable?

Oates

Did I say life is too long? You know, I’ve said many, many things. Sometimes I think I might just be joking. I think for most people life is not too long as it nears the end. When you’re thirteen and there’s a long summer, that’s different than when you’re eighty-three. But in the beginning, I think art was identification with religion. Religion and art spring from the same sources. The earliest kinds of art were probably conjoined with religious symbols. Both of them are ways of transcending, so that individuals are unified through a myth—that they’re all created by the elephant god or the turtle god or something. Then the turtle gets illustrated, so it turns into art, and the two come together, a way of making people feel they’re connected. Which is true—we are all connected, so the myth corroborates that. I’ll give another example of transcendence in art. Most of us, if we live long enough, will encounter people—maybe ourselves—who suffer from dementia and grandiosity and irrational behavior as they get older. It’s common and it’s mundane and demeaning and probably kind of awful. But the great play, the great work of art on that subject is King Lear. Shakespeare takes a universal experience and elevates it in this extraordinary play. That’s one of the great works of humankind, King Lear. If you contrast that with the experience of, say, going to an Alzheimer’s ward, seeing the difference between King Lear and these people: that’s what we mean by the transcendence of art. Shakespeare takes something horrible and transforms it into an occasion for extraordinary insight. Lear is blundering and irrational and almost collapsing but he rises to these insights about love and the meaning of life. When he dies at the end, there’s a new order as the young people come in. Tragedies have that form, where at the end there’s a new generation, so it’s like the death of the old way, as in Macbeth or Othello. It’s a quintessentially great work of art that takes human anxieties and tragedy and transmogrifies them into something like a new beginning. It’s very hopeful.