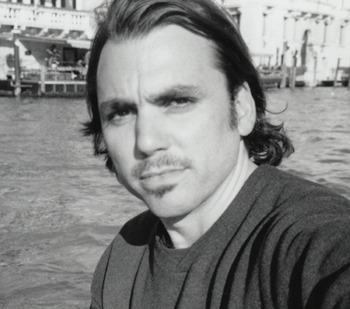

About Matt Bell

Matt Bell is the author of How They Were Found, forthcoming in Fall 2010 from Keyhole Press, as well as a novella, The Collectors, and a chapbook of short fiction, How the Broken Lead the Blind. His fiction appears or is upcoming in magazines such as Conjunctions, American Short Fiction, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Gulf Coast, and Unsaid. He is also the editor of the online journal The Collagist.

A Profile of the Author

Notes on “The Receiving Tower”

“The Receiving Tower” is a story set in a vague future but written in a diction and syntax meant to seem older, a stylistic pattern in my work which may have originated with this story but which has followed me throughout much of this past year’s writing. Once the language of the piece was underway—once the first sentences were written well enough that they could start pointing me toward what the next progression of sentences would look and sound like—then other supporting choices followed.

For instance, by the end of the first day’s writing I had decided on using Scottish names for all the characters, in an attempt to make the story feel foreign and estranged from our own day-to-day America (an idea I got from reading Brian Evenson, who often uses wonderfully disorienting character names, although I wouldn’t necessarily claim he picks his for the same reasons as me). The captain is the only character who remains nameless, both to distance him and to again make him seem like a character from an older tale—I wanted him and the other soldiers to feel like American civil war types, and so I set them in the harsh arctic setting, populated their days with a distant commander, a far-off war, a preoccupation with rations and coded messengers and constant accusations of treason. Even though they’re on land, trapped in their tower surrounded by expanses of ice and snow, I meant for the story to always feel confined, the far north setting framing Maon and his fellow soldiers like a band of would-be mutineers stuck aboard a ship lost at sea.

I also divided the story into small, numbered sections to add a journal-like feel to the story, even though the first person narratives within aren’t journal entries. I hoped this (very slight) confusion of forms would somehow complicate the ground truth of the narration by letting this diary-like sense make the story seem “true” even as Maon’s failing memories in the body of the story simultaneously make his telling of the story seem increasingly false.

Most of this I didn’t know about until I’d been working on this story for weeks, long after it already had a beginning, middle, and end. This was a story that started with a single image—the meteors falling through the northern lights over the tower—and absolutely nothing else. Discovering the rest of the story required dozens of iterations of key scenes and images and individual sentences, all of which required a lot of meticulous attention combined with an openness to revision and rewriting.

Notes on Reading

I get haunted by books, by novels and collections and poems and stories in magazines and snippets of fact or fiction that I pick up from web sites. For instance, a certain story will need to be read over and over, like Matthew Derby’s “The Sound Gun,” which “The Receiving Tower” certainly owes some debt to. Similarly, a certain book might need to stay close at hand, not necessarily to be read again in full but rather dipped into, as if to resample whatever it was in the book that affected me so much. I’ve reread Michael Kimball’s How Much of Us There Was and Robert Lopez’s Kamby Bolongo Mean River over and over this past year, not in a linear fashion but in a quicker, partial fashion. Last year I did the same with Evenson’s The Open Curtain, and the year before that it was Ander Monson’s essay collection Neck Deep and Other Predicaments and Charles Jensen’s chapbook of poetry The Strange Case of Maribel Dixon. I’ve read Sam Lipsyte’s Home Land every year since it came out, as I have with Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son for as long as I’ve known about it. Dennis Cooper’s Guide is so ingrained in my being that I can right now reach for my copy of it and open it directly to my favorite sentence, there on page 77, just before the halfway point of the page.

These are some of the ways in which my reading makes me the writer I am: The best words and sentences and paragraphs and even whole fictions tunnel inside me, and only the fever of making something new—of making the right something new—can get them back out. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.