May 21, 2008

MARK CUILLA, MANDY IVERSON, AND AARON WEIDERT

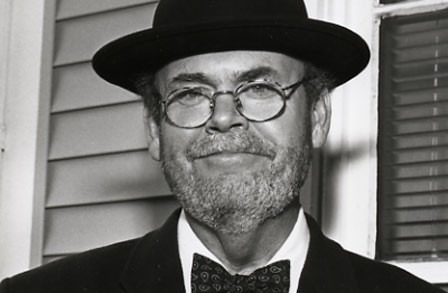

A CONVERSATION WITH THOMAS LYNCH

Photo Credit: Poetry Foundation

Thomas Lynch is Milford, Michigan’s funeral director, a job he took over from his father in 1974. Through his examination of death and mortality, Lynch has found much inspiration for his writing. But to label his work as being about death would be an oversimplification. A 1998 Publishers Weekly review stated that “The combined perspectives of his two occupations—running a family mortuary and writing—enable Lynch to make unsentimental observations on the human condition.” Though Lynch often builds from themes of death and grief, his writing moves across the spectrum of life, offering flashes of humor and insight along the way.

He says of himself, “I write sonnets and I embalm, and I’m happy to take questions on any subject in between those two.”

In 1970, Lynch took his first of many trips to Ireland, reconnecting with family in West Clare. He has since inherited the ancestral cottage there, where he regularly spends time. His relationship with Ireland is documented in his most recent book of nonfiction, Booking Passage: We Irish and Americans.

Lynch is also the author of three books of poetry: Still Life in Milford, Skating with Heather Grace, and Grimalkin & Other Poems. Lynch has also authored two essay collections: The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade, winner of the Heartland Prize for nonfiction, the American Book Award, and a finalist for the National Book Award; and Bodies in Motion and at Rest, winner of The Great Lakes Book Award. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, Poetry, the Paris Review, Harper’s, Esquire, Newsweek, the Washington Post, the New York Times, the L.A. Times, the Irish Times, and the Times of London. We spoke with him over lunch at Café Dolce in Spokane, Washington.

AARON WEIDERT

You associate a great amount of humor with death in your writing. Do you write with that juxtaposition in mind?

THOMAS LYNCH

I don’t set out to write anything “jokey.” But I do think that the way things organize themselves, the good laugh and the good cry are fairly close on that continuum. So the ridiculous and the sublime—they’re neighbors. I think that’s just the way it works. If you’re playing in the end of the pool where really bad shit can happen, then really funny shit can happen, too. And then there are times you just take on a voice, where you’re consciously thinking sort of in hyperbolic tones, and then, as long as you go with it, it’s fine.

MANDY IVERSON

Being an undertaker has obviously influenced your writing. How do you write multiple essays and books on the same subject?

LYNCH

I’m not conscious, starting, of where I’m going with it. I’ve said before, and I think it bears repeating, what Yeats said to Olivia Shakespeare—that the only subjects that should be compelling to a studious mind are sex and death. Those two, those are the bookends. And think of it, what else do we think of, what else is there besides that?

I write sonnets and I embalm, and I’m happy to take questions on any subject in between those two. I think most people are that way. I think most people drive around all day being vexed by images of mortality and vitality. All they’re wondering about is how they’re going to die and who they’re going to sleep with, or variations on that theme—what job they’re going to have, whether they’re tall enough or skinny enough or short enough or smart enough or fast enough or make enough money, and all of it plays into these two bookends.

If you’re writing about life, you’re writing about death. If you’re writing about life, you’re writing about love and grief and sex and all that stuff. Once I go outside those pales, I’m trafficking in what is, for me, not only the unknown, but also just not interesting.

IVERSON

Does a nonfiction writer need to have an interesting life?

LYNCH

My work as a funeral director is like most people’s work. Parts of it are routine and dull. Parts of it are hilarious. Parts of it are very, very compelling.

Alice Fulton is a poet I much admire and have been friends with for a long time. When she began teaching at Michigan, I said to her, “Alice, you might be better off waiting tables than teaching students, because you have such a huge voice and you don’t need any other voices interrupting you.” Teachers are constantly being interrupted by the voices of their best students. They have high volume, good students do. So I would think that if you find yourself waiting tables or doing brain surgery or professional wrestling, anything that leaves room for your own sort of imaginative leaps, you’re fine. You’re okay.

It’s handy to be a funeral director—because how we respond to this predicament of death is sort of baseline humanity. I’m very fond of sex, so that’s handy in the other subject that Yeats said was important. That works out well. But I can’t think of any work that you could disqualify from being just as interesting or just as much a metaphor for the human predicament.

WEIDERT

You talk about how your job has its dullness and routines and hilarity. Do you realize later that there’s something there to write about? If it’s not the dullness and not the monotony, at what point do you realize, This is something I could write about?

LYNCH

I’m a writer, so I don’t wait for something interesting. I write. Period. And if there’s nothing interesting, I’ll make it interesting.

My son’s a fly-fishing guide. There are days when the fishing isn’t good. But by God, no one ever goes with him who doesn’t get a good guide. Because he’ll take you down the river and show you things you never saw before. And you will feel the excitement of catching and releasing fish in the most unlikely ways and places. That’s a good guide. Not that you come home with a slab of dead fish, although there are people for whom that’s the deal. For me, writing means I use language about whatever. The world is open to me that way. So if I stopped being a funeral director, I wouldn’t stop writing or stop having things to write about.

For me, writing starts with a line, or some imagination, or some notion, and I just go with it as far as I can. And you know how this works, this idea that you sort of set yourself afloat on the language. And you think, I’ll see how far it can take me before this little raft I’ve cobbled together falls apart and everybody understands that I’m really just a fraud, or drowning—whichever comes first. But when it’s really working, the reader goes with you to the most unlikely places. They take big leaps with you. I think Frost said that “Every poem’s an adventure—you don’t know where you’re going with it.” But you go. And writing nonfiction, essaying, the personal essay, the familiar essay, is exactly the same as far as I’m concerned. This adventure where you are counting on language, you are trusting in the language to keep afloat whatever the notion or image or metaphor or intelligence or opinion or whatever it is you want to get across. The bridgings. And the nice part is that the times you sink, you don’t have to send them out there. Oops, you have to go back and revise it, tie the slats together in a different way, rope the little raft together and then send it out. And see how it goes.

WEIDERT

When the title essay in The Undertaking was first published in The Quarterly, it was titled “Burying.” They’re not quite the same—there are minor revisions throughout. Do you often continue to revise, even once work is published?

LYNCH

If you read The Quarterly, that would have been in 1988. It was later published in the London Review of Books—and Harper’s picked it up from there, and I probably made changes all along until it got into the book. I haven’t made changes since. Once it’s out in a book, you figure it’s done. Although, going back over, there are parts I remember in that Sweeney piece that I’d like to mess around with. I won’t be doing that soon.

WEIDERT

In “The Undertaking,” you write that people think you have “some irregular fascination with, special interest in, inside information about, even attachment to, the dead.” The implication seems to be that it isn’t true and yet so many of your essays deal explicitly with death. Do you see that as a contradiction?

LYNCH

In “The Undertaking,” I followed that up by saying something like, “A dentist is a dentist, but he has no particular fondness for root canals or bad gums.” That is sort of his office in brief, to take care of that, but what I wanted to point out is that it is not death—death as a subject is dull, mum, it says nothing—but all the meanings attached to the dead that are the basic stuff of human beings.

When anthropologists are trying to figure out the place at which that walking anthropoid crossed the human barrier, it is when the anthropoid began to notice its mortality. I mean, that is the signature event—that we do something about mortality. Other living, breathing, sexy things don’t. Cocker spaniels, rhododendrons—they don’t bother with that stuff. They don’t seem to care about others of their kind dying. We do. And that, to me, is the signature of the species. I could just as easily argue that all I’m writing about is human beings, humanity. And Humanity 101 is mortality. Humanity 102 is sex. Or maybe it’s the reverse. [Laughs.]

IVERSON

Quite a few of your essays deal with political issues: abortion, big business vs. small business, euthanasia. Do you think nonfiction writers have an obligation to engage with the outside world? Or even get political?

LYNCH

Both. We were talking earlier about the reason that poets aren’t read is because we don’t hang any of them anymore; we don’t take them seriously; we don’t think that poetry can really move people to do passionate things. But poets did. Poets could change cultures. Before there was so much contest for people’s attention, poets were the ones who literally brought the news from one place to another, walking from town to town, which is how we got everything to be iambic and memorable and rhymed and metered because the tradition was oral before it was literary. And I do think we are obliged. Maybe it’s not just to opine about the issues of the day, but I think we are obliged to step outside of our own work and consider other writers’ work.

Writers should review writers—to say, “This, you might like.” If we don’t have a go at the marketplace of ideas and writing and poetry and the rest of it, then how can we expect people to just take it up without any sort of guidance? That’s the great regret about the disappearance of the independent bookstore. You can buy a lot more books on Amazon, but you don’t know whether or not you’ll like them or why you should read them. Whereas you stumble into a proper bookstore, and someone on that staff has read the stuff you’re picking up and will tell you, “You won’t like that,” or “Yes, you will,” or “You should try that.”

I think writers, particularly poets, should be in the opinion pages and on the record about certain things. Now, some of that I come by only through experience; I remember the first time I got a call from someone at the New York Times—asking if I’d given any thought to the idea that we could find out who the Unknown Soldier was, from Vietnam, because they’d come up with the DNA technology. They had narrowed it down to two people, and they knew they had the DNA, and they knew if they disinterred the body from Arlington they could tell. And the question of the day was, Should we? They thought maybe I’d have an opinion about that. And I said, “Well, I’ve never thought about that, but now that you mention it, interesting thought. I’ll bet I would have something to say about it.”

And the editor said, “That’s nice. Can you give us eight hundred words by tomorrow at five?”

And I thought, Well, I’m an artist, and they don’t talk to poets like that. And I said, “Well, what’re you going to do for me?”

And he said, “Well, we’re going to give you a million and a half readers.”

And that’s like drugs.

And I said, “Fine, I’ll have it ready for you.” And I did. Course, whores that they are, they had sent out to several other writers—not so artistic, but faster—and they got what they wanted faster, and they booked it. But I did send the piece to the Washington Post and they took it. And I thought, Aha, this is how it works, to be ready for whatever’s there. I’ve been sort of fiddling with the advantageous ever since. I like the idea that eight hundred words could just [snaps fingers] tweak the world a little bit.

WEIDERT

Do you still do that?

LYNCH

Not all the time, but enough so that a year doesn’t often go by that I don’t have a couple pieces in. Because it’s a good exercise—then it’s just like targeting. I can remember thinking I wanted to say something about the wonders of the changes in Ireland, and I thought that St. Patrick’s Day would be the perfect day to get this published in the New York Times. Think of all the Irish-Americans who would read it. So I wrote this piece and I sent it to them the week before. I said, “Now, this is only good for one day.” And by God, they took it.

The nice thing is they title everything. You can come up with the best titles—they change them. But the title they gave it was the most brilliant one—“When Latvian Eyes are Smiling,” they called it, and I loved it, and they had the most beautiful graphic with it. It’s just like playing multidimensional chess with these people. Because they’re all smart young editors who care less who you are or what you do; they just want the best page they can get.

WEIDERT

I’ve read that you consider Dr. Jack Kevorkian a serial killer.

LYNCH

I do think of him as a serial killer, and so possessed of his own importance about his role. I’ve buried suicides, and I’m impressed by their resolve and it bothered me that something on the order of seventy percent of his “patients,” or victims, were women. It seemed like a bizarre and cruel kind of gender-norming. The known fact is that women attempt suicide by a factor of ten compared to men. And men, this is a funny word, “succeed” at suicide more than women. Kevorkian seemed to be like the helpful hand who would sort of level that playing field. But he was not killing terminal cases any more than nonterminal—except in the philosophical sense that we’re all dying—and so, for me, the slippery slope was not all that far between what he was doing and a clinic at the corner where my daughter would go if she didn’t get a prom date—and that’s a painful, painful experience. Why shouldn’t she be able to claim sufficient pain to get her assistance?

I mistrust judges and I mistrust lawyers and I mistrust politicos when it comes to life and death matters. I think they’ve made a mess of war. I think they’ve made a mess of capital punishment. I think they’ve made a mess of abortion. Not because I think there’s a right way or a wrong way to think about reproductive choices. Twenty-five years after Roe v. Wade we’re still carping about it—thirty years now. You have to say it’s not a great law if we’re still carping about it. Settle law when it’s settled, you know. Whatever the outcome, the way they got there was not right. Didn’t work. Hasn’t worked. I’m much more trustful of the woman who puts a pillow over her dying husband’s face to save him another round of chemotherapy. She’ll live with the moral implications, and she might even live with the legal implications, but I’d rather deal with those on a case-by-case basis than have this crackpot man in the van running around doing it.

The thing that was instructive to me was that the talk in the culture about it was so disembodied. It was all sort of like, Isn’t this a nice option; doesn’t this sound nice—“assisted suicide”—which is oxymoronic to begin with. I mean, take the words apart, and there’s no way you can do that. And it wasn’t until we showed it on TV, until we actually saw, that we went, Oh, that’s wrong. And then he went to jail. As soon as we saw it, we knew it was wrong. But for most of four or five years we were going around as if we were having a conversation about radial tires. So yes, I do think of him as a serial killer, and I think he got his proper comeuppance.

IVERSON

Do you have an agenda with your writing?

LYNCH

Well, there are times I do. Most times, the agenda is just to fill my office as a writer. I write. When I write a poem, I do it for the pure pleasure of having that poem on the page. They are to play with. But when it’s done, published, it’s like it has its own digs; you’ve done your part for it. But there are times when I’ve consciously set out to change the discussion on a particular topic. And I think Phillip Lopate is very instructive on this, when he talks about essayists being, among other things, great contrarians. I always look not for the “this or that,” but the “have you thought of it this way?” So that piece on abortion is not necessarily about abortion. It’s about reproductive choices, and the costs of them.

And I don’t know of anybody yet who has figured out exactly where I stand on abortion. I would think it a weakness of the piece if they could say, “Ah, he’s one of those.” Because the job of an essayist is not to be right, left, or center, this or that, but to make people think in ways they wouldn’t have otherwise thought—and to keep as many in the room as you can while you’re doing it. Barack Obama is doing the same thing in his campaign—he’s trying to keep people in the room.

I remember wanting to say something about the shame and sadness of this war and how to frame that. I was sitting over in Ireland in August one year, reading about the president going off to Crawford, Texas, and I thought, I’ll write something about the president and me, because he was on his ranch, I was on mine. So I did. And they took it, which was very nice, because it was another one of those pieces that was only good for three or four days, and they took it. I don’t think the president reads the New York Times, but people who work for him do, so at least it got to be part of the conversation.

WEIDERT

Have you ever had any backlash from that?

LYNCH

I wrote a piece about capital punishment, about Timothy McVeigh. It was the first federal execution in my generation. I’m from a state that doesn’t have the death penalty. So it was the first time that, clearly, I was one of those people they’re talking about: When “we the people” are killing McVeigh, I was one of them. This was my federal government killing this man.

I don’t know the answer to whether I’m for or against it; that answer is not available to me at the moment. But I do know that if it’s being done in my name, I should be there for it—or at least be allowed to watch it on TV. And the fact that they had prohibited that specifically was, to me, offensive. So I wrote about that.

Greta Van what’s-her-name, and Sean Hannity, they were all calling to see if I’d go on, and I said, “I don’t think so.” The letters to the editor were interesting, the ongoing conversation about it at the time. The same with the piece on reproductive choices—oftentimes, I’ll meet someone who has some vexation about that. And that’s good. I like that. I think we should vex each other. But I’ve never had a bad experience, I’ve never had an “I wish I hadn’t done that”—one of those moments.

With poems, I have. I once wrote a poem about a former spouse that was one of those poems that would have been better off tucked away and found among papers. That said, there was a therapy in it—in a very selfish way. But it was needlessly hurtful. I’d like to think I’ve evolved past that.

WEIDERT

Do you write poems that you know in advance will get tucked away?

LYNCH

I try to avoid those.

WEIDERT

You try to avoid writing them?

LYNCH

I try to write, period. And I think poetry is as good an axe as a pillow. You should be able to cut with it if you want to. But I do want to avoid hurting people inadvertently. I don’t mind hurting people I intend to hurt—but inadvertent damage is the thing I fear. And I think all writers are capable of it. You’re dealing with powerful tools, you know; words are powerful business. I’m not saying you should be guided by fear, but I think general kindness is still a better thing. It’s just evolution. We want to be better people.

MARK CUILLA

You deal with feminist themes in your poetry and nonfiction. Do you consider yourself a feminist?

LYNCH

I’d say humanist. I’ve read a fair amount of feminist literature, and I was a single parent for a long time, which I think, for men, makes them feminists.

One of the boxes you have to fill in on a death certificate is, “Usual occupation,” and the next one is, “Type of business or industry”—funeral director, mortuary, writer, that type of thing. For years, I would often have a son or daughter or a surviving husband say, “She was just a housewife.” And I can remember, after being the single custodial parent for years, thinking: You do it for a week and come back and tell me “just a.” Because the effort to minimize the hardest work I’ve ever done was offensive. I can only imagine what it would mean to a woman who had done it all her life.

All the women in my life have been powerful, powerful women with strong medicine—dangerous people. Every one of them. Some of them still are. My sisters are dangerous people. And my wife is a lovely, lovely person, but she’s a powerful person. I just don’t see them in any way, shape, or form as having ever traded on victim status. What’s irksome to me about so much of the third-wave feminism of the day is that it did seem to traffic in victim status. I remember being in Edinburgh one year for the book festival, and I was rooming near Andrea Dworkin in this beautiful hotel in Belgrave Circle. I’d read just enough of her to know I wanted to meet her and talk to her and have a little go-round with her, you know. I sent her a note asking for that. I put it in her mailbox and got no response. I then saw her in one of the tents in Charlotte Square, where they do the festival. I said, “Possibly you didn’t get my note, but I’d be very, very honored if I could take you for a cup of tea or coffee.”

“I won’t have time,” she said.

I came away from that exchange thinking, Well, go piss up a rope. I did feel bad when she died. She was a much misunderstood person. Like most of us, our own worst enemies.

CUILLA

Can you talk about the intersections between nonfiction and poetry?

LYNCH

I think that any kind of writing just depends on reading poetry. I can’t imagine ever wanting to write anything at all if I hadn’t first been completely smitten by poetry. I can’t exactly tell you what it was I was smitten by, or when, or what it was that I read. I keep having to pour the shit in because I can’t remember any of it, except bits and pieces. It’s really exciting when you come across a poem that just lights up the room. For me, it’s the thing without which nothing else would happen.

I think the poet—the fictionist, the nonfictionist—is trying to disappear in the words. I once commissioned a painting of the island off the coast of our house in Ireland. I said to my son, “I want a painting of Murray’s Island. Could you paint one to hang over the mantelpiece? I’ll give you enough money to make it worth your while.”

He set to work doing it and he’s out there, and he’s a perfectionist in all things and he was really getting agitated by this commission, you know. “What do you want?” he says.

And I said, “I want it to be unmistakably a Sean Lynch, and I want it to be unmistakably Murray’s Island.”

And he says, “Then I’ll have to disappear.”

And I said, “Well, you’ve got it. That’s exactly right.”

So it was one of those things where you would look at it and it’s unmistakably Murray’s Island, but it has his fingerprints all over it. And I think it’s the same with writing poems. Who it is that we’re writing, or what version of yourself you channel is sort of random, really. You can take on different voices. Nonfictionists do it, too, I think. Some days you come to play, some days you come to pray. It just comes to who shuffles in on the first sentence. And sometimes it shifts in the middle of it. What starts out as sort of basic expository writing becomes self-revelation. We don’t know how that happens but if done deftly it really does seem seamless.

It’s Montaigne who says that “In every man is the whole of man’s estate.” Just start concentrating on something. Write about your toilet habits, what you had for dinner. What’s that thing they always say when they’re testing you for a microphone? Tell us what you had for breakfast. I’d love to start an essay with what I had for breakfast and see where it went, just for the heck of it.

CUILLA

Much of your poetry clearly comes from the personal. Richard Hugo writes in The Triggering Town that “You owe reality nothing, and the truth about your feelings everything.” Does this hold true for your work?

LYNCH

Ah. Well, the way you frame the pairing, yeah. Things don’t have to be true in a—I mean, I’m not here to tell you all there is about how it was for me this morning, but there’s something truthful about my keeping a record of it. And then you recognize something in yourself or something that’s generally true of all of us.

When writing doesn’t work for me it’s because somebody sets out and they are too self-enamored. And I think this is where James Frey got in trouble. It’s not so much that he was lying; it’s that he was trying to puff himself up. He was telling us lies about his experience not for the sake of some other truth, but in the service of him—his own sort of heroic self.

And heroes are tiresome ideas today. They really are. Because a hero always knows the end. They’re going to win, or they’re going to save the day and save the world. Essayists don’t know the end. And poets don’t.

I think Hugo’s saying that the truth is, we’re muddling through. We’re going with the best of it. That’s the truth of it today; we don’t know the outcome of this. At least for poets and nonfictionists, this is the excitement, this is the “essaying” of it, this is the setting forth. Not that there isn’t some bravery, but there are no heroics. It does take faith that the language will do its part if you do your part. The word itself is good that way—all of the etymological roots of “essay” are really good there.

WEIDERT

You deal with religion and religious issues in your work, but your examination seems to change from The Undertaking, through Bodies in Motion, to Booking Passage, which deals much more explicitly with your own issues with religion. Could you talk about that evolution?

LYNCH

The longest piece in Booking Passage is an effort to make sense of religious experience as a part of faith experience. With that whole piece about the church, it was handy to have a priest in the family and to have his pilgrimage and his sense of calling to work with as sort of the anchor for that piece.

I think we are trying to find ourselves in relation to whatever the hell is out there. Maybe the relationship between myself and whomever is in charge here is changing as time goes on. The first essay in The Undertaking was written in 1987 because Gordon Lish said, “If you write this, I’ll publish it in a very important literary magazine that I edit,” by which he meant that there would be no pay. But it really was the first time my nonfiction was commissioned. And between 1987 and 2004, when I was writing the last of that book, one would hope that, as Muhammad Ali says, “We are different people.” If not, there’s something very wrong. And my relationship with religiosity is changing a little bit over time, too.

John McGahern, a fictionist I really admire, died in the spring of 2007. He had been sort of banned by the church in Ireland as a young writer. He had a brother or a cousin who was a priest, I think. Large Irish-Catholic family, orthodox upbringing. He had every reason to feel thrown out of the church and abandoned by the church, and his books were banned and censored, et cetera. Anyway, when he died, I was impressed by the fact that his instructions were to have them do the Requiem Mass and nothing more. He didn’t want any eulogies, or opinions, or any of the sort of post-Vatican II add-ons. He just wanted the old words. And that’s true—and maybe this returns to your question about poetry and essaying—that there is a ritual part of it. There is sort of an artifice to it all, sort of a structural beauty to it. I’m still trying to figure out how it works. I’m glad you noticed some change.

I was on a panel a couple of weeks ago at a synagogue, called, “The Same but Different.” They took the title from me. There were hospice people and social workers and clergy, and I was to give the keynote speech about funeral customs and bereavement and how we respond to death—that type of thing. The lunchtime panel was a rabbi, a priest, a pastor, and an imam. And one of the questions from the audience was, “Does religion ever get in the way of people?”

They all gave predictable answers until the imam said, “There is no trouble with Islam. Muslims, however, are troublesome.”

And I thought, Isn’t it just so? I haven’t any trouble with Catholicism or Christianity, but Catholics, myself included—and particularly the reverend clergy—can really put me through spasms of doubt and wonder. And here’s the difference: I have come to think of them as articles of faith, as something that the life of faith requires us to doubt and wonder and ask and mistrust and think it over and ask again. And to check into the book-making. We are people of the book, so we should check into all the acknowledgement pages, the tables of contents and all that stuff to see where they were first attributed. Because I think those boys got together and figured out a way to change some of the text.

And this is where I’m a feminist. The sooner they put women in charge, the better off we’d be. I mean really. I was four-square in favor of women in the military, but for the wrong reasons. I thought that it would reduce our appetite for war as soon as women started being killed. It hasn’t. And more’s the pity. When I was a much younger man, I said, “Instead of sending the young men out to do violence to each other for the sake of old men, which is how it’s always worked, send women out to do kindnesses—to old men.” [Laughs.] And there will be no war. Now, that’s probably not a feminist thought, but it could work no worse than what we’ve got going now.

IVERSON

In your essay, “Y2Kat,” you state repeatedly that writing is not therapy. However, in Bodies in Motion, you talk about writing in a way that makes it seem like a saving grace. Do you think writing is edifying?

LYNCH

Tell me about “edifying”—the word, “to edify.” Tell me what you make of that word.

IVERSON

Redemptive, maybe.

LYNCH

Yes. I love the idea of redemption from it. I do think—and here, I defer to Mr. Rogers—that if you can name the feeling, you can sort of keep track of it. What was Mr. Rogers always saying? “Name that feeling?” Hugo goes on to the same thing. Tell us the truth about that feeling, not the heroic stance, where it doesn’t bother me, but the stance that says, “That sucks and it hurts,” or, “That makes me want to strangle whatever.” Tell the truth about that. Yes, that can be redemptive.

And what’s more is that it brings around it a community of people who feel the same way or may someday be in the same predicament. That’s precisely why we read, isn’t it? To find out that we’re not crazy or are at least crazy in defensible ways, that other people have exactly these same responses. Hugo was right about that.

CUILLA

In Still Life in Milford, you quote, as an epigraph to the first section, an art exhibition guide that reads, “Subject matter is less important than personal vision, based at once on a physical intimacy with, and a metaphysical distance from the real world.” How does this relate to your work?

LYNCH

I stole that from the museum in London. They were having an exhibit with still life. The second epigraph contradicts it, doesn’t it? The first one says exactly what you’ve recorded, and I stole it from the Hayward Gallery in London, where I was at this exhibit. And the second one says, “It is difficult to make moral or intellectual claims from the arrangement of fruit or vegetables on a table”—which is what Still Life in Milford is. My point was, I was trying to make some moral and intellectual claims for just that. I don’t know about this first one. I can’t remember, now, what drew me to that—I’m sure it was the notions of physical intimacy with, and metaphysical distance from, the real world. I’m always drawn to the notion of the body in things—the corpus.

Part of my professional life has been marked by the disappearance of corpses in the funeral ceremony. Our culture is the first in a couple generations that attempts to have funerals with no bodies. We just disappear them. If you read the death notices in the paper today, you’ll notice that most of them are going to involve some type of memorial event, sans body, sans corpse. Also, most likely, without sort of the gloomy stuff that comes along with having a corpse in the room. But the way to deal with mortality is by dealing with the mortals. And you deal with death, the big notion, by dealing with the dead thing. And this you can try at home: Go kill a cat—see how you get through it.

Really, that story about the cat, “Y2Kat,” has it right, up to the part before the cat’s going to be dead. But after the cat died, the truth of it is that the way my son figured out how to deal with the cat’s death was by burying the cat.

We’re very good when it comes to cats and dogs. We just don’t have a clue when it comes to our people. We have them disappeared without any rubric or witnesses or anything like that. And then we plan these, “Celebrations of Life,” the operative words du jour. These celebrations are notable for the fact that everybody’s welcome but the dead guy. This, to me, is offensive and I think perilous for our species. So, in Still Life, one of the things I was trying to say is, Yeah, there is an intellectual—an artistic and moral—case that can be made for not only fruit and flowers in a bowl on a table, but also a dead body in a box.

CUILLA

There’s a series of sonnets in Still Life, and several sonnets in Skating with Heather Grace, and, at the end of Booking Passage, you write about your early work in forms. How much are forms still influencing your work?

LYNCH

They’re very handy for me. I love them, and form has changed a lot. I think one of the last poems in this new book is called “Refusing, at 52, to Write Sonnets.” I was younger then. It was a fifteen-line poem; I just miscounted. [Laughs.] Literally. And I’ve been writing sin-eater poems. Somehow, this guy turned up again. He’s been around since the first book of poems I wrote, and he’s always going to appear in twenty-four line apparitions because the first one was twenty-four lines, so having that form helps.

But form is such an open thing. There’s a poet, my dear friend Michael Heffernan. I probably would not write anything had I not met Michael Heffernan. Certainly, I wouldn’t have written books if I hadn’t met Michael Heffernan. Over the years of our correspondence, we’ve gotten to the point where we only correspond in poems; because we’re both old and cranky, we piss each other off, we’re both recovering alcoholics—you know, just land mines everywhere. We write poems back and forth and we seem to get along very, very well. So the form of the day is, I have to respond to what he says. He sends a poem called “Purple.” I send back one called “Red.” There’s the form. All it has to have is red in it. I write one called “Euclid goes to Breakfast with the Old Farts,” and he writes me back something Euclidian. So the form is very, very free flowing.

But having a task, which is the form itself—this is what I want to say about this, and I meant to say it when you asked about poetry: I think poets made up sonnets and sestinas and pantoums, and all those other epic forms because nobody was asking them to write poems. People could care less. So the poets thought, Look, I’ll give myself work to do. If I could jump through this hoop, surely they’ll be impressed. And they set off to write these different forms so people would say, “Oh, that’s very clever.” But they were making themselves do things they wouldn’t otherwise do.

And this is the hard part about essaying and poetry—that you’re setting out to do something you wouldn’t otherwise do and you have no direction; it seems like chaos. And when you finally figure it out, and when you finally get it right, it’s just joyous when it’s done. That’s true of poetry and essaying. When you make that leap across a paragraph or over a stanza, and the reader goes with you and you really land it, then you think, Ah, I’ve done something that’s never been done before.

I always tell my students that it’s very much like crossing water. And it is. You’ve got to give readers some sort of standing stones to grab onto. But if you make it too easy, they’ll get bored and fall in and drown. If you don’t give them any stones, they’ll say, “No, I’m not going there with you.” But if you can space those stones just perfectly, so that they can leap with you, when they get to the end they’ll say, “Why didn’t I think of that?” Sooner or later, they think they did think of that, and then they write something new. That’s how it works.