March 1, 2012

Tim Greenup, Kristina McDonald, Danielle Shutt

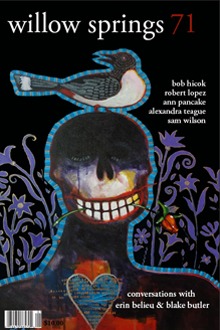

A CONVERSATION WITH ERIN BELIEU

Photo Credit: stlouispoetrycenter.org

Erin Belieu’s poetry moves. Each line break holds the potential for a rapid expansion of the poem’s emotional and imaginative reach. The result is sometimes unsettling, sometimes relieving, sometimes hilarious, but always wonderfully consuming. To enter a Belieu poem is to surrender to the paradoxes of the heart and mind, and reading her work feels like an act of liberation. Her lines are often chiseled and muscular; they propel readers forward with purpose. A hard-earned, well-worn fearlessness permeates her work. Take her recent poem “Perfect”:

Your sadness gets a perfect score,

a 1600 on the GRE,

but if I had a gun,

I’d shoot your sadness through

the knee. Then the head.

Or if I were a goddess,

I’d turn you to a tree with silver leaves

or a flower with a center as yellow as sunlight,

like they used to do when saving

the beautiful from themselves.

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, Erin Belieu is the author of three books of poems, all published by Copper Canyon Press, including Black Box (2006) and One Above & One Below (2000). Her first collection, Infanta (1995), was selected by Hayden Carruth for the National Poetry Series, about which she says, “I don’t know why Hayden selected me—maybe he had a cheese sandwich instead of a tuna sandwich that day, when he was looking at the finalists for the National Poetry Series.” We suspect more than chance was at play.

Her poems and essays have appeared in a wide variety of publications, from Ploughshares and Slate to The Atlantic and The New York Times. Belieu is a workhorse, on and off the page. She served as director of the creative writing program at Florida State University, and is currently the artistic director of the Port Townsend Writers’ Conference. She also co-directs VIDA, an organization designed to “explore critical and cultural perceptions of writing by women through meaningful conversation and the exchange of ideas among existing and emerging literary communities.”

We met with Ms. Belieu at a noisy bar in Chicago, during the 2012 AWP Conference, where she warned: “I’m a Libra, so every time I say one thing, I have to say the opposite.” We discussed her poetry, the importance of public service, the perils of technology, and growing up in the Midwest.

TIM GREENUP

Are you a Nebraska poet?

ERIN BELIEU

I am a one-woman chamber of commerce for Nebraska, which is the best of all states. I feel like that landscape is in me. There’s a way of being where I grew up, a kind of openness, a generosity. Maybe it’s because there aren’t enough of us to get on each other’s nerves. When you only have eleven citizens, it’s easy not to crowd each other. But my sense of enthusiasm and, hopefully, if I have a sense of generosity—it comes from that place.

But there’s also a kind of internal astringency Nebraskans have, a rub-some-dirt-in-it-and-stop-whining approach to life, and those things are part of me as well. In a lot of ways, I think Nebraska is where the West begins, and I think I have a Western mentality—as if that were one thing. Even though I’ve spent most of my adult life on the East Coast, I feel real affection and affinity for the West. I spend a lot of time in Port Townsend and Seattle because I’m the artistic director of the Port Townsend Writers’ Conference, and my press is Copper Canyon, and in some ways, I think I translate a little bit better in that part of the world.

DANIELLE SHUTT

You translate to me—and I’m from rural southwest Virginia.

BELIEU

Maybe you’re making a good distinction; it’s not geographical; more, as Donny and Marie would say, I’m a little bit country and a little bit rock ’n’ roll. I don’t feel the need to fuse those two together. I feel like that’s an interesting opposition. But, obviously, I have no real idea. I can sort of get hints through reviews, how people evaluate me, but you can’t think about that kind of stuff or you won’t write anything. You’ll spend all your time knotted up about how you’re being received. Let time sort that stuff out, and hope you’re lucky enough to have anybody reading your poems at all.

I don’t think I’ve ever fit neatly into anything. I’ve appeared in formalist magazines, I’ve been a fellow at Sewanee, but my poems have also appeared in magazines that focus on experimental and alternative forms. And maybe that’s been bad for my “career,” as if a poet could have a career; I don’t think Keats had a “career.” Poetry is a devotion, and it’s the closest thing I have to a spiritual practice.

I don’t mean to be cavalier. I have a great job. I’m able to feed my kid. I’m able to live in my house and buy groceries. For a poet, that’s a pretty big deal. I mean, I actually have health insurance. So I feel like I’ve been given this huge opportunity to be genuine and true in what I do. And I’ve also been given the gift to do things like VIDA, because I’ve got tenure, bitch! Academia doesn’t make you a bad poet, contrary to popular belief. But thinking of poetry as a career is definitely bad for your poems’ health.

SHUTT

Does tenure make people lazy?

BELIEU

It does sometimes, but that’s the opposite of what it’s supposed to do. It’s supposed to make you brave. I feel that if you’ve been given the gift of a livelihood, then you have a responsibility to others who haven’t been as lucky. I very much believe that. That’s why I helped to found VIDA with Cate Marvin. And founding a national feminist literary organization—well, that can put you on the hot seat sometimes. But I thought to myself, What’s the point of having tenure if I don’t use it to do what I think is important and necessary? Tenure should allow us to never grow too comfortable.

My father was the head of special education and gifted programs for my public school system, and my parents were community-oriented. They were involved in grassroots Republican politics, back when the name Republican didn’t equal bigots like Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee. But my brother and I turned out to be hardcore Democrats. And once my brother came out, my parents became Democrats. They were like, “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” I don’t think they ever voted Republican again. That made me really proud of them.

I come from a family where service was valued, so all my life I’ve had an urge to serve. I still have my First Class Girl Scout certificate signed by Ronald Reagan. I did something like 3,000 hours of community service. I was that girl. I was also on field staff for the Dukakis campaign, and dropped out of college for about a year and a half to organize all over the country. I’ve always believed in political activism. And that’s what I’m teaching my son to do, too. If you want your opinion counted, you have to step up. You better put your money where your mouth is.

SHUTT

Community is a dominant thread in your poems, too. Across your three collections, there are poems that engage people, whether it’s a poem dedicated to someone or talking directly to a historical figure. Could you talk a little about that?

BELIEU

My poetry is almost always written in response to someone, or it’s a portrait of someone. When I think of the fiction I most admire—and poems to a certain degree—it’s almost always novels that are social novels, like Anna Karenina, Middlemarch, and all of Jane Austen, where people are put in these social, moral, spiritual conundrums that reveal the essentials of human beings, what it means to be human. Robert Pinsky talks about how poets have a kind of monomania, an animating obsession, and I think I’m obsessed with understanding why people do what they do.

What does Mr. Bennet say in Pride and Prejudice? “For what do we live, but to make sport for our neighbors, and laugh at them in our turn?” I feel very much like Mr. Bennet sometimes, because people generally crack me up. But I have a lot of affection and sympathy for how ridiculous we are, all of us. The way we front and the way we lie, and our self-important posturing. AWP is such a weird little aquarium for that reason. Every variety of creature is on display. And I know I exist somewhere in the aquarium, too, but again, I don’t invest in thinking too much about how others perceive me.

My poems are frequently responses to some bit of argument I’ve encountered. I have a poem called “Your Character is Your Destiny,” which comes from Aristotle, and it talks about this idea of what it means to have a soul, and whether that sense of a soul is your destiny. Is it predetermined that we are going to move in the world in a certain way, and is that something we can escape? Are we stranded in a universe of hard determinism? I have just enough philosophy and theory to be dangerous. I’ll take a little bit of Aristotle or Slavoj Žižek or Lacan, and throw it out there, not yet necessarily totally understanding what they’re talking about. I just start with, Well, is my character my destiny? Really? I like to think out loud in poems, and find out what I think as I go along. Almost everything I’m interested in is dialectical; that’s where the tension in our lives is, where the tension in our art is. There’s all this absurdity around us, but there’s also the truly hideous. There are big and little tragedies. That’s why I love the poem “Musée des Beaux Arts,” where Auden points out: “About suffering they were never wrong, / The Old Masters: how well they understood / Its human position; how it takes place / While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.”

GREENUP

In One Above & One Below, the opening poem invokes the muse. Does the muse exist?

BELIEU

There are lots of ways to think about the muse. My background is in feminist and psychoanalytic theory, so when I talk about the muse, it’s my metaphor for those unconscious parts of ourselves, and wanting a fluid access to language and imagination. Being able to access these is the hard part. We’re surrounded by noise and advertising and technology, and it just gets more intense every year, so that voice, that inner muse, gets drowned out so easily. That’s one of the things the poem you’re referencing is about, the feeling that you don’t always have access to the thing that centers you, that part of you which, if you hold still and be quiet, will tell you something interesting.

There are many times in workshops that people automatically want to put poems in stanzas, because they’re overwhelmed by the idea of a three-page poem without stanza breaks. And I think, Wait a minute. Are we doing this because that’s what the poem needs? Or are we doing this because we’re now used to everything being in tidy graphs and sound bites?

Maybe that’s how forms change over time, because forms are just reflections of human beings and their preferences and what makes sense rhythmically and in rhyme at a given time. But I’m not sure how I feel about those things changing. We’ve turned into a collective ADHD society, in which a three-page poem without a stanza break seems overwhelming. We’ve become like flies that mentally zing from one thing to another, so we can’t settle too deeply into anything. I don’t mean to sound like a crabby old lady. You can see I’ve got my iPhone here that I check constantly. But I’m pretty sure I could go to one of these “back to the land” sort of things. I mean, I would complain a lot, but I could probably do that and ultimately be comfortable.

The technological world has created all kinds of wonderful opportunities, too, but—human beings as animals—I don’t know how we can keep up at this pace. We really have to struggle in a way that we didn’t use to in order to create a quiet space. Poetry is more often than not meditative—an interactive meditation between writer and reader— so that you have to have that still space to come together and discover one another. One of the things I love about poetry is that we have to be willing to hear each other. The reader has to be so active when reading a poem, which is why I’m grateful when anybody reads my poems.

SHUTT

You’re often compared to Sylvia Plath or Sharon Olds. What do you make of the critical impulse to construct genealogies for female poets from other women poets?

BELIEU

I think, sadly, there are so few reference points for women poets that it becomes really reductive. We don’t have this long, nuanced tradition to point to. It’s like, Oh, are you Elizabeth Bishop or are you Sylvia Plath? Like you’re choosing between Betty and Veronica in the Archie comics. There’s a lot in between, there are other options to make a comparison, but how many people have ever been able to actually name a good number of women poets? Happily, this is starting to change.

But so much of that kind of comparison just has to do with hype and publication, and that rarely has anything to do with what an artist is doing or why. I mean, seriously, I don’t sound very much like Plath. But some critics make lazy pronouncements and easy comparisons. And I guess they influence some people. But they don’t really know who’s going to be read fifty years from now; they don’t know who’s going to be read five hundred years from now, or how those writers will be received. Some people believe in heaven, and maybe they’ll look down and see their readership from there, but here and now, we don’t know. Which is why I think people who pretend, people who want to be kingmakers or tastemakers, I just find the whole thing tedious. You have your taste and you have what you believe in, and good for you. But to try to make that some sort of poetic law? You, my friend, are puny in the face of time. And that’s the way it should be.

I sort of play with that idea in a new poem, “Ars Poetica for the Future.” I imagine myself burying my poems in Ziploc baggies, because then I win. A thousand years from now someone will find my artifacts— assuming we don’t blow ourselves up—and I’ll be Sappho!

GREENUP

Where does that drive to become a tastemaker come from?

BELIEU

Probably insecurity—the urge to force everyone to believe what you think is truth, with a capital T. But there are poems I don’t love that I must respect. And there are poems that aren’t particularly of value to me that other people admire, and so I think, Well, maybe I need to think about this some more before I reject it. I’ve never been able to finish The Magic Mountain, no matter which translation I read, no matter how many smart people tell me to read it. And I’m pretty sure the problem’s not with it. I’m pretty sure the resistance is within me. But we grow into things when we’re ready for them. Usually the tastemakers are just fighting over power and turf. Which again, has nothing to do with literature itself.

Cate Marvin and I talk about this all the time. There are certain types who seem to think, Oh, there’s only one pie and I gotta get my slice before somebody else gets that slice, because the pie’s gonna be gone! And Cate and I both think, Why don’t we just bake another pie?

It strikes me as a profoundly anxious way of being in the world if you have to prove that you’re more by proving that somebody else is less. And that goes into that whole dustup with Rita Dove and Helen Vendler, when Rita had done an odd, inclusive anthology, which I found really revealing of her. It was a portrait of a reader, as if Rita were saying, “This is my expression of what I think is really right.” And she was willing to acknowledge her idiosyncratic way of thinking about things, and I thought that was honest. I was disappointed that Helen Vendler was so scathing, as if there were some objective truth she felt was under assault. And I think, But Helen, there are no objective truths about poetry. I know you have strong feelings about it and it’s your life’s work, and I have many good reasons to respect you, but we’re not talking about the nuclear codes here. Which is not to say I don’t believe in criticism, or that I won’t argue strongly for my point of view. I just keep in mind that more than one thing can be true at the same time. Sometimes even opposite things.

I don’t have any particular anxiety that poetry is going to hell and then the whole literary culture will die. Poetry is a lot bigger and badder than any of us. And what does Auden say? It’s a mouth, right? It is the mouth. “Poetry makes nothing happen” is a line people misunderstand frequently. He means poetry makes nothing happen directly. Not in the way of commerce and politics and scruffy immediate human intercourse. He’s saying something more profound: Poetry is essential in the way that a mouth and tongue are essential. It doesn’t go away. It’s not going to disappear if we don’t fight to the death about it. How about we try a little more humility in the face of the poetry mouth? Such ego, to think that poetry needs us to protect it.

There are the more immediate things like prizes and jobs that get people all wadded up, but beyond that, there’s the great fear that we devote our lives to this ephemeral thing and we don’t know if we’re right or wrong or how history is going to see it. It’s a total crapshoot. Think about all the writers who have fallen out of fashion, only to have people who were obscure come to the forefront. We don’t have any control over this. But I’m okay with that. I’m okay with being a minuscule dot in the universe. I’ve accepted that fact. I get to eat and drink and have sex and live in a body and I get to make poems and I get to love my son and I get to love my partner and I just feel like maybe that should be enough, and we should stop trying to control the future with our pronouncements.

I’ve never understood why people are so unnerved by the tininess of our human experience. It’s always made sense to me, ever since I was a little kid. We’re just biological blips in the wholeness of time. But what a lovely thing to be. What a gift. I just want to be recycled into a willow tree eventually.

SHUTT

There’s some anger in the poems in Black Box. In some criticism, I’ve read that anger—particularly in women’s poetry—is a limited emotion. Or if you’re a woman poet, writing about anger—it’s just anger that readers get out of your work. How do you feel about that view of anger in poems?

BELIEU

Women get smacked with that stick all the time, and I’m pretty— pardon me—fucking tired of listening to it. I feel like, All right, old man. I know you hate Sylvia Plath. Duly noted. Now move along. You’re boring me.

There was an unfortunate confusion about Black Box regarding the back matter. Black Box isn’t actually addressed to my ex-husband, of whom I’m very fond. We made a wonderful child. We’re still friends and raising a person together. I would not use a book to attack someone. Poems aren’t therapy and poems aren’t journals. Which, as a woman poet, it seems you’re often in the position of having to point out. I didn’t set out to write biography. I write poems, which are acts of imagination. It’s weird that I feel, as a woman, a need to explain that not everything I write is a transcription of my love life, my vagina, and my daddy issues. I actually make things up, and I care deeply about the form of the poems.

In Black Box, I was interested in the performance of grief, and grief as this multiple experience. Grief is so awkward in American culture— maybe it’s awkward in Vietnam and Canada too—but it seems to me a very American thing that you’ve got about two weeks to feel whatever it is you’re feeling. You have about two weeks of casseroles and people really focusing and saying, “How are you doing?” And then, understandably, as Auden talks about in “Musée des Beaux Arts,” people get back to their lives. But you’re still there with your grief. And a big part of grief, especially at the end of a love relationship, but also at the death of a loved one, is anger.

I’m interested in feminist issues and I’ve read a lot of feminist theory, and I was interested in this idea that in some ways female anger seems like our last great transgression culturally. I’ve always been fascinated by how anger is performed by women in literature. Or not performed—sometimes it seems to me it’s enacted through depression, through passive approaches. Eleanor Wilner, a poet I admire immensely, did a translation of Medea. And in her introduction, she deals with this idea of a woman whose grief is so angry, so epic, that it consumes her entire life and her children’s lives. She is vengeance incarnate—suicidal, homicidal, operatic, terrifying, and truly pathetic. I was really interested in trying to achieve and sustain that pitch as I was writing the poems in Black Box. Honestly, I wanted to see if I could write an exorcism. The exorcism as form. That was a fascinating challenge.

So, especially in the long poem “In the Red Dress I Wear to Your Funeral,” the speaker keeps taking on different masks. At one point, she’s a Borscht Belt comedian. At one point, she’s the Bride of Frankenstein. At one point, she’s the voice of a Ouija board. She keeps trying on these costumes and putting them aside and taking on another costume to dramatically perform her sense of betrayal and loss.

I am very aware of anger—of female anger—as transgressive. And female anger is something that’s not spoken to often in poetry. Or anywhere, really. I think of women artists who’ve addressed this feeling directly and the backlash is usually intense. Very much a how-dare-you reaction. Which is absurd when you think of how surrounded we are by expressions of male anger in our culture. How venerated they are. Male rage is cool! But female rage is still disturbing, displacing, abject, unnatural. Except it’s not. It’s normal. And more than any other poem I’ve written, people come up to me and say, “Thank you for writing the Red Dress poems. They’ve meant a lot to me.” Which is about the nicest compliment anyone can ever give you. And I think parts of the “Red Dress” sequence are pretty funny. I meant them to be funny, because they’re so over-the-top. It’s worth noting that the poem’s title comes from a quote in the movie Moonstruck, which is a satire. Or like that scene in one of the Batman movies, when Michelle Pfeiffer plays Catwoman, and she’s standing in her latex suit looking totally vatic, and then she just says, “Meow,” and boom! It’s funny and intense and a little scary all at once. And I was like, I wonder if I could write a poem that can do that.

Anyway, that’s a long way of saying I’ve always been interested in this issue, and I wanted Black Box to perform that. Some reviewers got it, and some reviewers—which is typical of the way women are reviewed— focused on what they thought was biographical information. I wonder how it would have gone if that information hadn’t been there. I have a poem in my forthcoming book, Le Déluge, called “12-Step,” and it’s about lighthouses and taking an A.A. pledge not to write confessional poems. Obviously, another satire. Because I feel like there’s nothing safer, nothing less likely to get you in trouble, than writing about lighthouses. I can say, Oh, this isn’t about me; there’s nothing personal here. I’m just a wee poet writing about the landscape. Objectively.

KRISTINA MCDONALD

I believe you’re working on a memoir about your son. How’s that going?

BELIEU

The fun of working with nonfiction has been that it’s not poetry. It’s a different set of problems to solve, formally. And that’s been a huge pleasure. But then I got to a certain point where poems started to come again and I sort of put the nonfiction on hold.

It’s also a difficult subject. My son has a mild form of cerebral palsy. Jude appears as almost completely typical; if you saw him, you’d go, “Oh, cute kid.” But when he opens his mouth—his speech is deeply, deeply impacted because he was strangled by the birth cord when he was born. But the thing about a kid like Jude is—I mean, people say, “Oh, he’s a miracle!” and in a way, Jude really is a miracle, because the fact that he was impacted as little as he turned out to be is very unusual. He should have been dead. He should have been damaged beyond recognition. And he turned out to be this wonderful, smart, beautiful—freakishly beautiful—kid. One of his teachers referred to him as a radiating joy machine, and he does naturally exude joy. He’s one of those people whose smile comes from the inside.

But imagine what it’s like to be such a person and also to have 99% of the world unable to understand you when you speak. It’s been a journey—to have the gift of him, but also the responsibility of him, to try to help him figure out how he’s going to live in the world. His speech has gotten a lot better. If you were to listen to him now, he can make himself understood. But his journey is ongoing. He’s only eleven, and so part of me feels like I wrote to a certain point, but I don’t yet know the end of the story.

GREENUP

In an interview you did with Saw Palm, you described writing a poem as “like being a diamond cutter,” in that it “requires great powers of concentration.” How do you keep your concentration?

BELIEU

I don’t, honestly. I get distracted all the time and that’s my biggest challenge—to find the space for poetry. I’m a full-time mom. I have an academic job. I’m the artistic director of the Port Townsend Writers’ Conference. And these are all things I enjoy. But my biggest challenge is finding the time to sit in a quiet space and make work.

I’m back to it again, but I still struggle to make time. Of course, I run around like a chicken with my head cut off. I mean, I walk in the house and I’ll think, Okay, I gotta go to a meeting, then I’m gonna pick up the dry cleaning, then I’m gonna go get Jude, then I’m gonna come back here to meet the washer repair guy, then I’m gonna meet a student, then I’ll go grocery shopping, and then I have to go to a reading.

I really want to have a commune, like a poetry commune where we all have a big island, and if you want to have kids, we help you raise your kids, we take turns, just a big family, and everybody has writing hours. I feel like this would be a very cool thing to do. Though, as we’ve seen, it’ll all go to hell. I mean, look at the Manson family.

But, you know, when your kid is young, it’s probably not your most productive time as a writer. And that’s okay, because I like Jude more than poetry. He’s my poem in progress. And the world is not going to freak out with, “I can’t go to bed because I haven’t had my next Erin Belieu poem!” They’ll be okay.

GREENUP

When you do get the time, is it something that you can access quickly, or is it something that takes some digging to get back to?

BELIEU

Sometimes it takes digging and sometimes it’s right there, and it really depends on the day and how mentally healthy I am. If I can brush off, in a Jay-Z-like fashion, the voices in my head about how, “She’s too this,” or, “She’s too angry,” I can get clean and write what I want to write.

The big difference between being a poet at twenty-five and being a poet at forty-five is that I’ve spent a lot of time considering what I believe about poems and polishing my formal chops. I have strategies. I’ve read a lot. I’ve learned a lot. It’s good for younger poets to know that time helps you. I mean, unless you’re a totally useless git, after a certain amount of time, things stick to you, and you don’t have to worry so much anymore.

What I do worry about is what’s worth saying. Do I need to write a Persephone poem? Does anyone need to hear that from me? Maybe not. I don’t feel this necessity to put anything out, and I don’t think students should ever feel that pressure. It’s not a career, it’s a devotion. Find other ways to live your life, find other ways to make money, because God knows there are better ways than poetry. Put your energy into finding a way to maximize the amount of time that you have to write.

Some poems I’ve had to work very hard for and considerably fewer have been gifts from my lesbian personal trainer muse, but it’s amazing how many of the ones that were free flowing are the ones that are often anthologized. And I’m like, “But I worked so hard on this other one!” and they’re like “No, no, we want the one that was really easy. We like that one best.” But it’s all part of the process, because that ease probably comes from the hard work of the ones you ground out.

A good example: When my first book came out, I was working at AGNI as managing editor and I got a call out of the blue at my office from The New York Times—not something I’d ever had happen to me— and they said, “Um, we like your book Infanta, and we want to feature one of your poems in The Times this week, and we’re doing a feature on the subject of Labor Day. We would really like it if you could give us all the poems you have on Labor Day.” They said, “You have poems about Labor Day, right?” And I was like, “Yes. Yes, of course I do. It’ll take me some time to go through those many poems I have on the great lyric subject of Labor Day and choose the right one for you.” And I hung up the phone and I was like, The New York Times! Labor Day! Okay, what do I do? Because I was not going to miss the chance to have a poem appear in a place that my parents had actually heard of. So I whipped off this poem called “On Being Fired Again,” which is now one of my most anthologized poems. I didn’t sweat for that poem at all. But for the majority of my poems, I have totally sweated and I feel stupidly wounded that certain ones haven’t gotten more attention. But that’s exactly why you have an audience. The audience wins, the audience decides. And you can’t argue with the audience. You just shut your mouth and say thank you.