February 26, 2014

Kristin Gotch, Stephanie McCauley, Kate Peterson

A CONVERSATION WITH CATE MARVIN

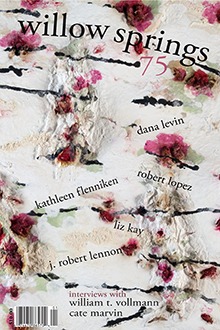

Photo Credit: Ploughshares blog

“How I would love to be the speaker of my poems!” declares Cate Marvin in an article published in the Los Angeles Times. “For then I should know such liberation.” This liberation is exactly what draws us into Marvin’s poems. Her speakers are free to love, to seek vengeance, to exert authority.

Marvin grew up in Washington, D.C., the only child of a military intelligence analyst. Although she admits she was often unhappy as a junior high and high school student, she found salvation in poetry. Marvin defines poetry as “sacred space.” Her poems are constructed with surprising images, insistent music, and textured language, as illustrated in the following lines from “Landscape with Hungry Girls:” “There is blood here. The skyline teethes the clouds / raw and rain’s course streams a million umbilical / cords down windows and walls. Everything gnaws…” The images are surreal, but the poem’s experience remains tangible, and each line break creates a raw, stunning musicality.

Marvin is the author of three books of poetry, including Oracle, forthcoming from Norton in 2015. Her debut collection, World’s Tallest Disaster, won the Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry, and her poem “An Etiquette for Eyes,” which first appeared in Willow Springs 72, was chosen for Best American Poetry 2014. Critics often compare Marvin’s work to Sylvia Plath’s, but as Jay Robinson points out in his review of her second collection, “It’s difficult to classify the poems of Cate Marvin’s Fragment of the Head of a Queen. Of course, comparisons are handy, but inadequate, and claiming Marvin akin to Plath is off the mark. For one thing, Marvin’s poems are more narrative than Plath’s. And also, Marvin goes places not even Plath would dare.” Marvin’s poems are often bold, but her purpose is never solely to shock; rather, she aims to portray a complex range of human emotion.

Cate Marvin holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Houston, an MFA in fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and a PhD in English and comparative literature from the University of Cincinnati. She serves as Director of Operations for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, and teaches English at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York. We met with her in her room at the Hotel Max in Seattle during last year’s AWP Conference, where we drank wine from coffee mugs and talked about motherhood, risking sentimentality, and “lying like the truth.”

KRISTIN GOTCH

One of my favorite poems from your first book, World’s Tallest Disaster, is “The Whistling Song from Snow White.” I love the speaker’s sense of confidence in lines such as “I command. Make yourself look like you want to get fucked / because in my land, nobody gets fucked over…”

CATE MARVIN

I wrote that when I was twenty-five, so it’s nineteen years old. I was writing pared-down poems at the University of Houston, and my instructor, an amazing poet, Adam Zagajewski, said to me, “Your poems are anemic.” That was part of a series of poems where I was letting myself swagger a bit. I remember writing that poem and knowing it was a moment of change for me.

That was a good summer for writing. I was working with a lack of self-consciousness and a better idea of who my reader might be, maybe someone like me. That poem is very much a statement of poetics; I was claiming my turf. Poetry has always been a sacred space for me. It saved me. I was a miserable high school student. I started writing when I was eleven, didn’t fit in, like most poets, and poetry was the thing— I realized when I was seventeen—that I was going to do. So when I went to a graduate program, I had a very high notion of the importance of poetry. In some ways, I had to reclaim what poetry meant for me. When you’re in that situation and you’re duking it out, you have to be strong. That whole change was like, I’ve got my own motherfucking country. This poem is my land and I make the rules.

I was talking to a friend of mine and asked if she recognized Free To Be You and Me as a reference in that poem, and she said, “I’ve heard of it.” But if you were born in the late sixties or early seventies, and you had progressive parents, you would have known that record, Free To Be You and Me, by Marlo Thomas. It’s like, we are all equal and everything’s cool. The notion of equality we know now is problematic. But at the time, you were raised to believe you could be anything, the American dream. The irony of that is thinking you can be president, and then realizing that, well, no. And then, there’s this assumption: Oh, well, I’ll get married. And that becomes your worth—someday someone will marry you! That’s why romantic comedies trigger such sentiment in us. Because they provide catharsis. We’re taught that this is what to hope for, and if we don’t get it, then we did something wrong as a woman.

KATE PETERSON

Are you going to let your daughter watch romantic comedies?

MARVIN

I’m going to let her watch anything. My parents let me read what I wanted. They were very open-minded. I was reading adult books, explicit books, at a young age, and I don’t think it messed me up. I don’t think we can prevent our children from seeing things today, with access to the internet. I don’t want my daughter to find porn sites online and I intend to figure that out as I go, but parenting is something I try to compartmentalize. I try not to worry too much about what’s going to happen five years down the road, because I have tomorrow to handle. My kid asks a lot of questions, and a lot of them are about death. We’re dealing with mortality now. A good friend of mine died last summer and several of my daughter’s fish died, so she’s curious. I get nervous when she’s crossing the street, because she’s like, “Oh, well, and then we’ll die.” Most parents will tell you their kids have predilections to certain things, often gendered. There’s not a lot you can do about that, and if your kid likes princess stuff, you’re going to let her dig princess stuff, because that’s what makes her happy. Of course, later on you can talk about the larger issues. My daughter’s not interested in princess stuff. She’s interested in dinosaurs and unicorns and animals. But she asks me every day if she looks pretty. A lot of that comes from people telling her she’s cute, and her girlfriends evaluating each other’s outfits every day. One day she came home from school—she was four—in a very bad mood because no one liked her outfit. This has been disconcerting for me. I was not a cute kid. I was skinny, with buck teeth because I sucked my thumb till I was eleven, and I had not the greatest haircut and was a total tomboy. My daughter is blonde—she’s not blonde anymore, but she was when she was a baby—and she has gray eyes, so it’s weird, because I have brown hair, brown eyes. I never thought I would have a kid that was fair. It was interesting to watch people dote over her when she was a little blonde girl. It felt like something that separated us.

STEPHANIE McCAULEY

In past interviews you’ve mentioned that earlier in your career you were too busy with school and writing to be in a successful relationship. But now you have a daughter and you’re finishing a third book—how do you manage everything? What’s changed?

MARVIN

I made the decision to have a kid when I was thirty-seven. I found out I was infertile, so I had to do IVF. I had to make a decision pretty much then and there whether or not I wanted to have a child. I wasn’t prepared to make that decision because I thought, like all of us think, that we can wait until we’re fifty to have a kid. That’s not really true. It’s actually quite difficult. And I still haven’t found a relationship that will work for me. I got frustrated thinking I would have to settle for a relationship in order to have a child. When I found out I had to start undergoing fertility treatments, I was told that most clinics would probably show me the door. I had to make a decision, and I decided that it would be for my work and my life. I had spent so much time by myself, smoking cigarettes and holed up reading books and writing poems, I felt like that could come to a very poor end in terms of my life—not the persona of my poems, but me. So I got pregnant. It took three tries.

Having a child changes everything and changes nothing. My life improved by having a kid. But you’re really much the same person. In some ways, you’re almost more who you are. But you have to kind of fall out of love with yourself. Narcissism has to go out the window. That’s painful, to break up with yourself. Juggling it all has definitely slowed my progress, but a couple of things have happened. First of all, I write differently now, and because I was writing so much for so long, I can work on a lot of stuff in my head. I also work on things over a very long time. I was working on a poem last night that I started in 2008, when I was pregnant. I’m finishing that up, and rewriting it again. The process is different now. You don’t actually get the time to sit and write, but you write differently, and if you’re a writer, you have to write and you end up writing things in spite of yourself.

So what happened to me is that I discovered I had a book. I didn’t think I had a book, but when I pulled together my poems I realized I had a manuscript. It was not the third book I’d planned to write, which was some dense, elegiac, almost philosophical thing. This book is more irreverent than my previous books, weirder in a lot of ways, because I had to do away with some filters in my life.

I recognized that having a daughter was ordinary, and before that I had lived comfortably with a sort of special woman’s status. I almost thought of myself as a guy in some ways, and you can’t think of yourself as a guy when you’re so obviously not. Then you have this kid with you and people are criticizing you or blessing you, and you’re pushing the stroller around and you can’t be at the house. When I found out I was going to have a daughter, it scared the shit out of me. I thought, Oh, my God, this person who I already love—it’s really weird when you get pregnant, you’re just like, I love this kid already; I don’t even know this kid. I was convinced I was having a boy. When it was a girl, I was like, Oh, my God. No.

Having a kid has made me figure out I have to say no to a lot of things. But it’s also forced me to take some downtime I might not have otherwise taken, because if your kid wants to go to the park and play, that’s all you’re doing. And it’s nice. I’ve met a lot of people as a result of having a kid. I used a sperm donor to get pregnant and I know a lesbian couple who used the same donor. They’re part of my extended family and our daughters know each other as sisters. As an only child coming from a small family—just me and my parents—it’s nice to have that extension and to sort of move in other parts of the world. My kid is like a living poem. She says stuff that blows me away. It’s wonderful to have that kind of love in your life. It puts everything into perspective. But I don’t worry about what my daughter is going to think about my poems. My writer’s office is separate from me running around day to day.

McCAULEY

You mentioned realizing you had a book. How does it compare to the first two?

MARVIN

I don’t know yet. Wallace Stevens has a great quote from the essay “The Irrational Element in Poetry,” and I’m just going to paraphrase it, here. He says: I don’t know what the poem is going to be, except it is what I want it to be once I make it.

The sense is that you have to accept the poem on its own terms. You have to feel it and dress it and allow it to create its own shape. It’s almost like I picture an invisible form I’m putting clothes on so people can see it. This new book came out of nowhere. In a lot of my projects, I’m interested in the post-confessional mode, taking it further. It’s a good rhetorical mode for talking about some things people aren’t necessarily ready to read—what I call stealth poems. I don’t know if I can speak to that yet. I also haven’t gotten to the point in the press kit and stuff where I get asked a bunch of questions and I look at my book and say this is what it’s about. Right now I can say that it’s about death in a big way and, in some ways, it ends on a rebirth. It’s full of elegies, and while I wouldn’t say it’s slapstick, there’s a lot of whacked-out humor in it.

PETERSON

Can you expand on what you mean by the stealth poem?

MARVIN

The stealth poem is something I was doing unconsciously when I was at the University of Houston, where they like you to have nice, neat, quatrain poems, a tight, shapely stanza. You can have chaotic and unseemly content in a poem, but visually, when it’s crafted really well, it impresses; you can imply any number of political opinions or agendas in this poem that are not necessarily picked up by the reader, because the reader is like, Oh, well, this is a very well-made poem. It’s what literature does all the time—makes the reader empathize with someone they may not have previously empathized with, whether they know it or not, because they can see themselves in the speaker. It’s a kind of code; women have been writing that way for a long time. As have queer people, as have people of color. It’s something I do a lot less of in my third book.

PETERSON

You mentioned that your daughter is talking a lot about death and that your third collection is about death. Do you think your daughter influenced your third collection?

MARVIN

No. My book was done before my friend died of liver failure. She was my age. It was very unexpected. A good friend died in 2005 and that was hard, because he represented to me the most awesome way to be in the world, a very funny, offbeat person who connected with a lot of people in a way that was contagious. He enjoyed life. One of the problems with our culture is there’s no proper way to grieve. Poetry can be one place to explore that.

GOTCH

I want to go back to what you said about “The Whistling Song from Snow White.” You said that up until that point your poems were “anemic…”

MARVIN

My undergrad poems—people would get appalled at what I wrote about. I’m tame compared to how I was then. I’ve learned over time to have a better understanding of how I’m coming across, how I might be affecting my audience. One of my flaws is that I can be oblivious. That’s a bit of a gift, because it means I’ll say things and not think too much about them and not realize people are taking me seriously and are like, What the hell is she saying? Maybe some of that comes from not being heard for a long time. When I was in junior high and high school I was unhappy, and that particular generation, the parents were like, Okay, you’re unhappy, deal with it; we’re going to work now. When I first asked to see a shrink, it was like, No, you can deal with your problems yourself. It was a typical suburban upbringing, but it was existential for me, the way I think it is for a lot of kids, and even more painful because you can’t put a finger on what’s wrong. Or it doesn’t seem legitimate to be in psychic pain. I went to college and was among people I had a lot in common with, but when I was in high school, I was a bad student. My self-esteem was for shit. I think some of that comes out of not actually thinking anyone will care.

McCAULEY

In your essay “Tell All the Truth but Tell It Slant,” you say you’re pleased to discover that you “tricked someone into believing the world of [your] poems is true.”

MARVIN

I don’t want to waste my reader’s time. We’re not on this planet for long, and I get frustrated with indulgent writers. I know I’ve been indulgent at times and I apologize for wasting anybody’s time, but I really do try, first of all, to be entertaining. I write a lot of poems no one ever sees that are boring, self-indulgent—no one wants to hear about my cats. But you want to write about everything. So anything that comes to fruition, the stakes have to be high, there has to be an emotional input on my part, I have to feel convinced in the poem. All of that has to do with language, with creating something unique with language, so that every line or phrase is something no one has encountered before, something actually changing someone’s experience of reading, something visually and viscerally communicating, giving someone a scene or an atmosphere or an experience. You want your poem to be interesting, you want to know that there’s trouble, great trouble, that something is going to happen. As far as tricking someone into believing the world of the poem is true, all the best writing is trickery. It’s lying like the truth.

McCAULEY

So, trickery is actually good for your readers?

MARVIN

Absolutely.

McCAULEY

It’s not manipulative?

MARVIN

Manipulative has a bad rap. Rhetoric is manipulative; all language is manipulative. When we use language we are moving to get something we want. We’re always making arguments for something, always trying to negotiate a space. If you know your way around words and are good at manipulating them, that’s good. On the other hand, if it’s a formula you’re using over and over to manipulate someone, that’s a lie. But if you’re writing something that you can’t even believe you wrote, and you yourself are convinced of the truth of it—I mean, sometimes I write something and the experience of the poem becomes that experience itself in some ways. I think it’s naive to think that any writer who’s good is not manipulative.

GOTCH

In that same essay, you mention how Sylvia Plath’s work was criticized based on facts from her personal life. People are still reading Plath and other poets that way. I had a professor tell me never to read Plath. He had reduced her poetry to a cry for help. Why do you think readers mistake intense emotion for autobiography or a cry for help?

MARVIN

It seems like a reductive way to approach a craft that is endlessly changing itself, endlessly complicated and fascinating. That view of Plath is conservative, old school, pretty much over. It was supposedly “uncool” to like Plath when I was an undergrad, but I loved her anyway—I wrote a seventy-page paper on her. I also think that to dismiss the personal in poetry—that kind of dismissal almost always takes place when it’s women’s poetry. People are sympathetic toward Lowell’s plights or John Berryman’s plights. In those cases, within the confessional mode, the transgression is to display weakness. For female confessional poets, the transgression is to display strength. Your professor said Plath’s work was a cry for help. This individual was probably not Plath’s intended reader, probably didn’t grasp the irony of her work. You have a poem like “Daddy” and it works on multiple levels. It employs the second person, it seems like a dialogue, but it’s not. It seems sincere, but it’s not. It’s mercilessly artificial. It winks at women with irony. Every woman loves a fascist. Plath knows every woman loves a fascist and, of course, in life, no woman loves a fascist—she’s working off of that fifties advertising jargon. There’s a lot packed into that. Also, one of the primary things you learn from Plath is craft. From her syntax to her punctuation, she’s a master. She keeps a poem moving.

PETERSON

In the conversation “Your Silence Will Not Protect You” between you and Erin Belieu, you mention that you have born the brunt of the “angry poet persona.” How do you feel about readers inventing a Cate Marvin from what’s on the page?

MARVIN

You’re probably doing your job pretty well if someone thinks they know you. I can’t take issue with that, but I would hope my poetry is challenging enough that people don’t come to it with a reductive interpretation that my life is on the page. I get frustrated with that because it’s silly, though it happens to pretty much every writer. People make assumptions. I make my students swear not to show their work to anyone outside the workshop for the semester because I don’t want a boyfriend, girlfriend, mother, father, grandmother, grandfather, reading their work. They need to understand that their poems will be written for people they’ve never met and never will meet. Those are the people they’re going to move. If you’re really ambitious as a writer, those are the people you’re writing for. If you’re worried about someone reading you, you don’t experience the liberty of writing whatever you want and shapeshifting, being whoever you want to be. Poems that are fun to write are fun to read.

A student once said to me, “Aren’t you scared to put these things out there?” I don’t have a sense of people paying a whole lot of attention to me. I go through life pretty oblivious. I’m not especially paranoid, I’m not especially self-conscious. I spend a lot of time by myself and I am just like, you know, poetry is this other world, so I can’t really worry about it.

PETERSON

We listened to one of your poems on YouTube, “Yellow Rubber Gloves—”

MARVIN

I had no idea that had been unleashed onto the world. That’s fucked up. And that poem’s very Plathian. I was totally thinking of her. I hope you laughed.

PETERSON

It’s so powerful. I didn’t really laugh, I just felt like, Yeah, this is it.

MARVIN

The thing about the speaker in the third book…she’s getting old. She’s aware of herself in relationship to younger women. She’s not nice about other women. There’s a poem called “Poem for an Awful Girl” that’s about competition with other women and jealousy. It sucks to get old, to realize you’re not in the running anymore. With “Poem for an Awful Girl,” I’m plotting this woman’s demise. She has the guy I want. But then the speaker realizes that this woman she’s wishing horrible things upon isn’t even aware that the speaker’s alive. The speaker’s talking about needlepointing, and she’s at a needle point. It’s like this focus for women, that there’s this division in some ways which is funny, because I love my students and the age they are, and I hang out with them all the time and they’re my favorite people in the world to talk to, but I’m always registering the fact that I’m older than them and worried about that, freaked out that I even got this old. There’s also this thing like, Don’t be so carefree, don’t think it’s all so good because look at where I am now.

GOTCH

The speaker in “Yellow Rubber Gloves” seems to have a direct purpose when it comes to relationships—could you talk about the impulse behind that poem?

MARVIN

That poem has an autobiographical impulse. In fact, there are a lot of autobiographical impulses in my third book. It’s more personal in a lot of ways, more connected to my actual life. I’m not ashamed to say that, because the poems, I hope, completely transform that, and I don’t think anybody should be ashamed about the personal. I think women are often made to feel bad, that their writing is inferior because it is not “objective,” because they are writing inside their experience—but that attitude directly invalidates female experience, or anybody’s experience. It’s like, We don’t want to hear your complaints. You’re just whining. So in “Yellow Rubber Gloves,” I was married and always washing the dishes. I was the dishwasher and I used yellow rubber gloves because my hands would get fucked up if I didn’t use them. There’s a disaster to the situation, being in servitude and washing someone’s dishes all the time. I was a PhD student and writing. I decided I wanted to reclaim the term “confessional.” I was like, If you’re going to damn me as being confessional, then I will be confessional in a way that will scare the shit out of you. That’s been really fun, because I think it scares people who should be scared.

The poem started back in 2000. I started with the image of the centaur. But the mop and stuff, the whole idea was that the end would be like, Oh, my paramour—. But how do I confess this, how do you tell the new lover where you’ve been in a past relationship, that you’ve been denigrated? At the time, I had this new lover who’s mythologized in the poem as Pan. But how do you explain that you’ve been defiled and still seem whole to someone? I always wanted that poem to work. I’d show it to my friend, my main reader, and he was like, No, no, no, and I would rework it. And then I finally just finished it one day, not too long ago, one of the last poems to go in the book. I was doing this big run, writing poems all day and night to finish the book, and I just wrote it. It’s a general address to women. It’s also like this huge, you know—I’ve cashed it in. I’m ready, I’m done with it, I’m going be that old woman with cats.

It’s meant to be awful in that way. It names it, like, Yeah, I’m the fucking cunt who should have shut her hole long ago. I was laughing the whole time writing it. And I think you should use rubber gloves when you wash dishes, because I am a huge proponent of skin creams and lotions and I’m like, Use gloves!

So it’s supposed to be funny and awful, but the thing is—be careful out there, just be fucking careful. Because you could spend a lot of time negotiating relationships where your time to write is being taken away maybe by someone who is not a writer who thinks maybe, Oh, you’re not spending enough time with me, and if you live in New York or anyplace you can take public transportation, you know the ease with which men take up space on a subway. And there is a whole tumblr or tweeting thing of photographs of men taking up space. All women writers—it’s like we’re here, tucking into ourselves because we’re afraid. And that’s no way to live.

PETERSON

A lot of your poems go to uncomfortable places. Do you ever think to yourself, I shouldn’t write this?

MARVIN

No. I’m kind of compulsive and revealing. My father was a military intelligence analyst and his whole life was about keeping secrets. Whenever I feel like I shouldn’t say something, that means I’m about to blurt it out. For me, typos or coming across as sentimental are far more embarrassing than saying something unseemly. I’m working on a poem right now that has patches of sentimentality that I really need to work out of it. I’m rewriting it line by line, to wring that out.

GOTCH

What is sentimentality in poetry?

MARVIN

Well, with women it’s often a rhetorical device employed at a point when the reader’s not expecting it, and it gets them. It’s like in the movies, a technique. I guess we should look at the definition of sentiment; is sentiment less than love? What is it about sentiment that makes it bad? Is sentimental not beautiful? You know, hell, we’re all sentimental at some point, aren’t we? Because love leaks into sentiment. People are worried about sentiment, worried that people will be sappy or something and write love poems. I don’t know. I actually think sentimentality can be used as a rhetorical weapon in some ways. Like very ironic sentiment.

GOTCH

I think there are people who confuse sentimentality with love, like in a love poem—as if, just because it’s about love means it’s sentimental…

MARVIN

What would Pablo Neruda say about that? What would Garcia Lorca say? It’s easy to make someone feel bad about expressing a feeling when we pretty much go around feeling things all the time—that’s part of being human. I don’t like poetry that doesn’t have feeling in it. And you know who also didn’t write poetry that doesn’t have feeling in it? Robert Frost. A lot of people looked to him as the model for neo-formalism, but Frost was a tormented person, suffering a lot of the time. So it’s interesting to see what’s happening in his poems. He says, “No tears for the writer, no tears for the reader.” Okay, so let’s see. Sentiment. Exaggerated or self-indulgent feelings of tenderness, sadness, or nostalgia. Exaggerated or self-indulgent. I guess that’s the problem with sentiment, or that’s the criticism, but I think if you didn’t have some sentiment in a poem, you might not have the whole pallet of human emotion. I want to create an emotional atmosphere in my poems.

PETERSON

Jonathan Johnson says poets should risk sentimentality. Why does it have to be a risk?

MARVIN

Because it’s always a risk. It’s a risk when you’re in love with someone, a risk to reveal your feelings; it shouldn’t be but it is. In a poem, if you’re sentimental in the beginning, you’ve already given it away. It’s the writer’s job to seduce. You’re not just going to walk in buck naked and be like, Here I am. You have to lure them in from the title on.

McCAULEY

That goes along with T.S. Eliot and the New Critics and the idea that personality shouldn’t factor into reader response.

MARVIN

T.S. Eliot is always saying the opposite of what he means. When he says there’s an absence of personality, he means that in some ways you can be anything, but it’s clear that absence actually allows your real self to be present. The way he states these things, it’s always sort of wonderfully complicated, like the objective correlative, which is where he’s just making an argument that you should employ figurative language, that you should show, don’t tell. It’s Ezra Pound all over again. Eliot is interesting because you can mold him in a way to make many of his statements advocates for just reading a poem on its own terms, reading a poem by its own rules.

McCAULEY

So the self-sacrifice and the extinction of personality can actually allow for the personal?

MARVIN

Personality is, in some ways, almost a process, because what he’s talking about is like body odor. He’s talking about the state of personality. Where it’s like with poetry, you can’t be that person, you can’t be the daily person—in some ways it’s like getting rid of personality to allow a voice in.

PETERSON

On the back of your latest collection, Rodney Jones says that, “The work bristles with the intellectual and emotional contradictions that face single women of this time.”

MARVIN

I asked him to take out “single” and it didn’t end up getting taken out. I didn’t think it was fair. First of all, sometimes I’m single, sometimes I’m not. In fact, when a lot of that book was written, I had a serious boyfriend who helped me with a ton of those poems—Matthew Yeager, who is now a good friend, a brilliant poet, who totally understands my poetics and helped me get through this book. “Muckraker” is a poem he saved. I’d thrown my hands up and was done with it. It’s probably the best poem in the book. So, sure the speaker is not having such a great time with relationships, but she’s having a lot of relationships. She’s not single. She’s maybe kind of getting around a little bit.

McCAULEY

So a woman has to be either single or married.

MARVIN

I guess facebook gives us those options, right? I mean, what if you’re married to a fucking idea? You know, I’m married to poetry. It’s like what Adélia Prado, the Brazilian poet, says in her poem “With Poetic License.” She says, “I’m not so ugly I can’t get married.” She says, “When I was born, one of those svelte angels…/ proclaimed / this one will carry a flag.” She says, “It’s man’s curse to be lame in life, / woman’s to unfold. I do.” And that’s sort of like saying, “I’m married to poetry.” Rodney is one of my favorite people in this entire world and it was important to me that he blurbed the book, because he’s an exquisite poet and one of my mentors. I also wanted to show that someone who is a male, Southern poet gets it.

PETERSON

What are the emotional contradictions he was talking about?

MARVIN

Contradictions women face all the time regarding what they’re told by media, what they’re told they should and shouldn’t be. We’re told we’re on the brink of death every moment we leave the house at night; if we wear skimpy clothes, we’re probably not only going to be raped but probably deserve it. That’s what culture tells us, what media tells us. And women are adaptable, we kind of go along, we’re going to be friendly and kind and shit like that. But what we’re doing is accommodating a vocal and almost banal expression of violence toward us all the time. It’s not just women who see this—plenty of men see it and find it repugnant too.

GOTCH

In Fragment of the Head of a Queen, you have poems that seem to be written from a male perspective, such as “All My Wives” and “A Brief Attachment—”

MARVIN

That’s a female speaker in “A Brief Attachment,” a female speaker in a relationship with a woman. I tried to make that explicit. There’s something ironic about that poem, because the speaker is a poet, and has this attachment, this affair, with a younger poet who is really driving her crazy, but who is also someone to admire. There’s a lot of arrogance on behalf of the speaker. That’s what the poem is about. Both of the characters are problematic. That poem riffs off Thomas Wyatt’s “Noli Me Tangere.” Do not touch. It’s trying to work off of Wyatt, a sixteenth-century poet, but it has a lesbian spin, even though people expect the speaker of this book to be heterosexual. I thought that would be amusing. Twisted. That poem deals with a great unease regarding sexual ambiguity—bisexuality or homosexuality. With “All My Wives,” I was reading a Michael Burkard poem that had that line, “All my wives,” and it just clicked for me. That poem is strange. And ominous. There was a reading series in New York where actors read your poems, and this actress read that one and scared the fucking shit out of me. Basically, that speaker is the figure in “Muckraker,” a silly, arrogant man. But I also like him. You know how fiction writers say they like all their characters? When I read that poem, I am so him in that. But of course, he’s totally evil. He’s also pathetic, because he’s just this high-dictioned combination of two of my ex-boyfriends, someone I dated when I was twenty and then someone I was married to. I assumed that attitude. It’s kind of like, Oh, I see how he sees women. And the whole thing is like, Why would I desire to look in your eyes when I could pick up a book? “It’s like buying a book I’d never want to read,” he says. But also, you see in the end, he’s scared because he knows there’s this animal sense, that there are women waiting for him and he’s talking about his inheritance as a man.

PETERSON

You dedicated your second collection to boys and their mothers. What boys in particular are you hoping to reach and why?

MARVIN

That’s a cynical dedication meant to operate as a technique in the book. And the book, there’s a lot of criticism in there inherently about gender norms and stuff like that. At the time, I was frustrated with mothers who hadn’t let their boys grow up, because there are a lot of boys out there who need to be men. But I’ll also say that that was a dedication to my ex-boyfriend, who I love still. He’s a brilliant poet, Matthew Yeager, and the book was originally dedicated to him, and I probably should have kept it dedicated to him, but I was bitter about our breakup and I was sad and lonely. I felt like his mom was overprotective and had sort of been the one that came between us, and I think that was probably a miscalculation on my part. I was talking to a colleague of mine, a guy, and I said “Maybe I’ll dedicate it to Catholic boys and their mothers,” and he said, “Why don’t you just dedicate it to boys and their mothers.” It was a last minute change that went through. I think it’s funny as hell.

McCAULEY

What’s the difference between boys and men, or a factor that makes boys men?

MARVIN

Basically, just taking responsibility for your actions, taking responsibility for yourself, something a lot of people quite far along in age don’t feel obligated to do. It’s hard to do. It’s hard to be like, Hey, maybe I didn’t do that right, maybe I wasn’t very nice to that person, maybe I need to actually step up and mentor someone, instead of criticize them. That’s something I’ve come to realize, especially since having a kid, but also just because now I’m in the middle of my life. I work with college students and I don’t want to fuck it up for them. I remember the people who helped me and the people who did not, and how much it meant to me. So, I take that role seriously, and while I’m certainly not, like, a noble person, I’m sure as shit going to try to be the best person I can be. I have a lot of good examples in my life, friends with exceptional character, who I’ve learned a lot from. I’ve met a lot of these people through VIDA. This is a long way of saying I think everybody should try to be their best selves. It’s hard. I mean, God knows, wisdom comes too late.

PETERSON

Regarding VIDA, in what ways are women still underrepresented?

MARVIN

It’s fascinating that underrepresentation can still be so blatant, especially in so many progressive magazines. It’s always been obvious, but people would get angry if anyone brought it up. I was very lucky to see Francine Prose read from her essay “The Scent of a Woman’s Ink” way back, maybe in 1998, when I was at Sewanee Writers’ Conference. I had read that article in Harper’s examining the question of whether or not women write a certain way. Does a woman have a certain voice? Can you tell it’s a woman writer? I have a lot of male friends, and I have a lot more female friends now that I am involved in VIDA. But a guy I was good friends with didn’t really see what she was getting at. He just dismissed it. That stuck in my craw.

I have a lot of dialogue with male poets. I’m interested in what it means to be a man in a poem or to express masculinity in any way, because the activity of literature is learning what it’s like to be someone else. So, at the time that VIDA came about, I saw the essay by Juliana Spahr called “Numbers Trouble” in which she looks at an avant-garde anthology and sees how skewed the representation is. And I thought, I am always counting the authors. I go down the table of contents and I count, and I’m like, Oh, look, there’s three women and seven men. I know other women do that, too. When I started VIDA I had a lot of conversations with a lot of female writers, and I was like, We should count everything, which struck me as funny because I’m bad at math, but we started what is now known at the VIDA count.

There’s a disconnect between what some magazines produce and their readership. The majority of readers are women. Women can read men, women can read across the board, we’re trained to read both genders from a very early age, because we’re forced to read stuff that’s male focused. Then we read stuff on our own, books that are more about women. And we are the biggest consumers of literature. So it seems misguided. There’s a learning curve for these magazines to actually serve their readership; it’s important that they look at the numbers. It’s not a blame game. That’s too easy. We all have our biases. I’ve had to question a lot of my own since starting VIDA. Both Erin Belieu and I were schooled in the male canon. We have both had to look at what we’re teaching, look at our reading lists and ‘fess up. We can’t blame anyone but ourselves for the fact that we are not representing a diverse enough group of people in our classes. And that’s about growing, about not being reactionary and defensive, but saying, Okay, we’re all part of this. Why is it happening? There are going to be a million reasons. A lot of it’s shaped by capitalism and what

people want to sell.

GOTCH

We did an interview with Joyce Carol Oates in which the VIDA count came up. One of the interviewers mentioned that after the count in 2012, Tin House started digging into their own numbers and noticed an equal number of men and women submitting to the journal, but men being five times more likely than women to resubmit.

MARVIN

Women, for a myriad of reasons, are not willing to come back to the table right away. I can speak as a mother—maybe I don’t have time to submit like I used to. I used to submit like a man, but now I can’t be bothered. I think women need to put themselves out there more. We all have to, and it’s scary. But one of the great things about being a writer is that it’s kind of not you, except when you publish and people know who you are. When you’re starting out, though, no one knows who you are. You could be a ninety-two-year-old grandmother. That’s the liberty of poetry. I don’t have my body dragging along behind the poem. You know what it’s like to walk around being in a body—it’s what W. E. B. Du Bois calls Double Consciousness, being aware of having this identity, but also being aware of your identity as a person. That’s a conundrum.

GOTCH

Joyce Carol Oates mentioned a woman she’d published, the first submission this woman had sent in forty years. Because she’d gotten a rejection, she stopped writing. Joyce Carol Oates was like, You’re a really amazing writer. Where have you been all this time?

MARVIN

In our forums for VIDA we hope women of different generations will be conversant with one another. In the older generation there are a few very prominent women and a ton of women who are fine writers ushered into this invisible realm. They feel out of touch with younger female writers. And the fact is, we all are dealing with the same obstacles. Whatever genre we write in, whatever aesthetic group we call our camp, if we have a camp, we’re all facing that difficulty. Our work is not only not fairly represented, given that we’re half the population, the production of our art is being hindered by the fact that our work is not represented in these venues. Because the cold fact is that publications that are anointed are often gateways. If someone has a poem or short story or essay in something or they produce a play or publish a book with a good press, they’re going to sell books, a library is going to adopt that book, reading clubs might adopt that book. Maybe an award will give them a foot up to a better job. If they’re teachers, they might get a lighter teaching load. Maybe they’re applying for grants and the publication will provide a better chance of getting that grant. All of these things are going to give them more time to write. That’s why the VIDA count is important.

Everyone involved in VIDA has their own particular reason they’re involved. Mine is because I’m interested in women’s literature and not just the literature I produce. I don’t even know half of what’s out there because all these voices are being vetted for me as a reader. It makes it difficult to access people I could really enjoy. For me, reading fiction is a pleasure, like eating chocolate. I have much more access to poetry because I’m in that world. But some of these boundaries between genres and between aesthetics have harmed women writers. We’ve felt isolate and haven’t seen how connected we are to one another. We’re all disenfranchised, all struggling to find time to write, all struggling for validation. And the conversation is really going public now. I hope what VIDA can do on its website and when we have a conference (I hope in a few years), is create a space where you can learn about women’s literature. That seems to me like a totally intellectual undertaking, just wanting to know that stuff. Part of this is my education and educating my students. And also keeping literature alive.

VIDA focuses on literary arts. We can’t focus on everything. But there are a lot of organizations for women in different disciplines doing similar things. There’s a woman who writes about women in Hollywood. Women are forming organizations in every single discipline, and it’s not just women who are disenfranchised. I opened the Missouri Review the other day, because we received it as part of our count, and there were pictures of the authors on the front page. They were all white. Not a single writer of color in the whole issue. As we work to diversify VIDA, that’s something increasingly problematic.

PETERSON

I saw your Twitter conversation with Roxane Gay regarding that and was wondering how you might move forward to solve that problem.

MARVIN

I don’t know about the word “solve.” One person’s solution might not be another’s. “Solution” is actually sort of a scary word. But I think, first of all, we have to make space for the conversation and work practically. That’s what happens in a nonprofit—you think about what you can do. You start with ideas, with what you want to change, but then you have to think about action. You have to do it as a group, an incredibly collaborative project. I’ve never worked like this in my life. We’re having our first board of directors meeting on Friday—we have a larger board now—and a women of color initiative is going to be a big topic. We need to look at what it means to diversify the count. That’s difficult because the whole identification issue is tricky. What I would like to do is seek the assistance of like-minded organizations representing underrepresented people. It’s also an issue of class, which is the most invisible thing. Regarding solutions or strategies, you have to work with the help of so many people to get something that is really effective.

McCAULEY

When young writers look at the data, how should they use it? How do you consider it in your own writing?

MARVIN

As a poet, I don’t have to worry about this so much. I did the first count with a few people in the summer of 2010. I would use the public library and I didn’t have any daycare because I was too broke. I teach sometimes at Columbia, so I’d end up using their library or the New York Public Library, and it was hard work, in the trenches, and depressing when you’re doing it, because you find that some information can be presented in such a way graphically that you think there are more women being represented than there are. Then you look at the numbers, and you’re like, Oh. You’ll think, This is a really good issue, with a lot of women, but you look and there are only four. You start to realize that “a lot” of women to you is actually not a lot of women. It’s just what you’re used to. So what do young writers, what do old writers, what does any writer do with that data? Well, no one is going to look at those charts and feel good. But it also depends on what your aspirations are. You write because you have to write. And if you’re letting that tell you your writing is not important, you’re going to be in a lot of trouble. It’s a long, tough, gratifying life, but you already have been doing something that nobody wants you to do, if you’re doing something interesting.

In some ways, women writers have an advantage because we write a “minor” literature, and so we’re not so much heard. In some ways, our literature is extremely provocative, is some of the most exciting literature being produced. It’s an advantage. Not having time to write, that sucks, but fighting for it and knowing it’s important, that’s good. And a lot of people will say, “Oh, you won’t have time to write. If you have this job, you’re not going to have time. If you have a kid, you’re not going to have time.” But if writing is a priority for you, you make time, whether it means you have to say no to a bunch of things or slack off in a bunch of things.

When I was trying to figure out whether or not I was going to have a kid, a friend of mine said to me, “I promise you this, you won’t ever write again.” So I decided I wasn’t going to have a kid. Then I started to think about it, and it’s one of those things where you’re doing that squirrely thinking at the back of your mind, mulling it over, and I thought about her photography and how she had not pursued it. No shame in that. That’s her business. But I would rather be dead than not write. If I couldn’t write, there’s no point in anything. So I thought about it and I was like, I’m conditioned to work really hard. Having a child is a lot of work—in some ways it’s not work, but it is work, too, you’re caring for your child. You love your kid. But it’s not like you’re going to some fucking horrible office where you don’t like the people and you have to make photocopies when you’d rather be doing something better with your time. You’re hanging out with a human being you love. So I was like, I think my friend’s version is not my version.

PETERSON

Some male characters in your poems come across as not so great, and some people ask, “What’s the deal with these men?” But are men ever asked this question regarding women in their work? Is it a double standard that people ask you about the men in your poems?

MARVIN

A reviewer of my second book said that he imagined several ex-boyfriends had nosebleeds as my book went to press, a very uncool thing to say. You know from that book that there are a ton of poems that aren’t about men. In fact, that assumption might have been more applicable to my first book, a book with a woman’s voice in the tradition of a love poem, in the tradition of the troubadours, of Petrarch, a book about unrequited love. It’s a young book, the viewpoint of a young woman. People will take those poems and use them as a mirror, and say, “Where are you in this?” But it’s not supposed to be a mirror. It’s not supposed to look back at the woman, though that’s what we’re accustomed to, because typically the woman is the muse or the object in a poem. The woman is not the object in those poems in my first book. That’s why she’s a little unnerving, because she’s strategizing. She has issues of control.

PETERSON

She’s thinking a lot, too, about her situation. There’s one poem, “Me and Men,” in which the speaker says, “I can’t blame them for owning what I wanted back when what I wanted was had only by men.”

MARVIN

What’s really funny about that poem is that whole play with language at the end, where she’s like, I would rather think about animals that I’ve had, the idea being that men are the animals she’s had. And what’s really funny—and this is how utterly guileless I can be as a writer—when I was writing that, I literally meant, I would rather think about my pets. And then I was like, Oh, genius! I trumped myself— language did its work for me. That poem deals with what we do when we’re thinking about marriage or being with someone. We see a pool of people—and I don’t care what you’re orientation is, you think, Okay, who am I going to be with, because I’m supposed to be with someone. Maybe this one or maybe that one will work. It’s such a fucked-up way to go about connecting with people. The speaker’s making a gross generalization. That poem is really about one person, though it shouldn’t be interesting, being only about one person. But one person in a relationship can represent a lot of people. We all know this, I think. We return to archetypes in our lives. It has a lot to do with the mythology we create within our poems if we’re writing personal poetry. It’s recognizing patterns.

You ask about the men in my poems. The thing is, I’m kind of obsessed with men. It’s always been a struggle for me. I’m heterosexual. I often wish I wasn’t, but I am interested in men, and interested in how I will get a man to see me. Maybe it’s a desire to be validated, but it’s also a desire to communicate. I’m also confused by betrayal and dishonesty, and in the landscape of relationships, that’s where a lot of that shit goes down.

PETERSON

When you say you’re confused by betrayal and dishonesty, do you mean you’re confused that it happens or confused about how to react?

MARVIN

I’m confused that it happens. I know that sounds naive. That mummy poem by Thomas James has a speaker who blacks out in her father’s garden and her body is being prepared to be mummified. She says out of the blue that she’s going to come back to her life, back to the garden; she’s going to meet her young groom. His eyes will be like black bruises. And she’s like, Why do people lie to each other? It’s a really good question. It’s something my poems work hard against.