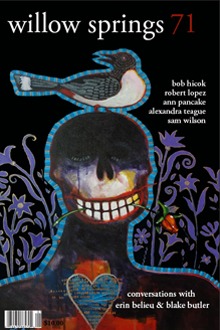

“Our Own Kind” by Ann Pancake

IF THEY CALL ME ANYTHING behind my back, they call me tomboy. For my brother, they have many names. Where we live, there are several ways to be a girl. To be a boy there’s only one.

I’M THIRTEEN, AND IT’S THE COLDEST WINTER I’ve ever known. The river behind our house freezes twenty-four inches down and stays that way for two months. There is a wildcat strike in the southern part of the state, our county can’t get coal for the school furnaces, and we’re out for weeks. I escape the house to walk the ice.

I wear a pair of my dead grandfather’s boots that my father dug out of a closet for me when I outgrew my others. Lucky for me, my grandfather was a small-footed man. The boot tread is worn nearly as glassy as the ice, so after I climb onto the river, I move with a deliberateness that makes me feel bigger than I am. I know the safest ice is a beautiful and transparent bright brown, and I lie on it face down to marvel at paralyzed bubbles, wonder how it holds given all the vertical cracks. The risky ice is opaque or white, and sometimes I play with it, creep out on it until the thrill capsizes into panic. If I’m really worried, I throw rocks ahead of myself and listen. My father has taught me thickness by ear, and not once do I crash through without knowing that it’s coming. Never have I walked an openness as long, as wide, as this frozen river, so few passages in my Appalachian world untreed, unhilled, like this one is. Solitary, unwatched, emboldened by the boots, on the ice I fill myself clear to my skin.

I know what my brother is doing while I’m out on the river. He’s holed up under his covers in his frigid bedroom rereading his books about Hollywood stars. There are fifteen months between him and me, so neither of us can remember a time the other wasn’t, and neither can remember a time we didn’t fight. Sometimes we go at it body to body, shoving, punching, hurling each other to the ground. More often we tease and goad and name-call-“pick” our mother calls it, but we both know the word “pick” isn’t brutal enough. Occasionally I enlist our four younger siblings to gang up on him. We lie in the bushes and pelt him with crabapples when he rides by on his bike. He tries to do the same, make a let’s-get-Ann club, but he’s usually less successful than I am because I’m the oldest.

As I leave the river and head home, everything is hard. My boots shatter dirt clods in the front field. Grass hummocks crunch under my weight. Puddles that should have evaporated weeks ago hold solid as wood right to the ground. It is a dry winter with little snow, and the snow that has come cannot melt and doesn’t lay, but coasts around until it catches on fencerows, tree trunks, steep banks, and crusts over. Even without touching it, I feel the parchedness of that snow in my mouth. Back at the house, Sam closes his Hollywood book and puts a piece of paper on top. Begins another in the tornado series he’s been drawing for the past couple of years. Wizard-of Oz-inspired, he rides his pencil in urgent black loops until he’s coiled a funnel cloud, then adds, spinning out of it, bathtubs, houses, children, pets-all that it’s sucked into itself on its rage across the land.

I DON’T KNOW HOW MUCH PEOPLE SAY to his face, but I do know he is never beaten up, never even touched, at least not outside the family. Decades later, he will tell me that back home in West Virginia no one ever called him “fag.” That didn’t happen until he went to college, where Pennsylvania and New Jersey boys did. But when we are kids, people occasionally do say things to me. “What’s with your brother? Is he gay?” Or, “Why’s your brother such a woman?” Some of the questions are sneering, jeering. Some are innocent, uncharged; the asker genuinely wants to know. In grade school, the questions are confusing. By junior high, they mortify.

When we play cowboy as pre-schoolers, our sister Catherine and I are Little Cal and Big Cal, thrusting on our rocking horses-there are only two-in hats and holsters. Sam always volunteers to be Mary Jane the cook, happy to trail along on foot with a tea towel around his waist for his dress and a diaper over his head for long hair. His pretend friend is a girl named Judy. Mine is Boogle, of indeterminate gender. I like Daktari and Lassie. He favors Bewitched and The Julie Andrews Show. I want to be Newton, the centaur in the Hercules cartoon. He wants to be Mary Poppins.

As we get older, Sam stages plays featuring himself, the four younger kids, and me when I deign to join in. He cobbles together ingenious costumes pulled from beds, closets, curtain rods, all to fabulous effect until one of our two audience members recognizes them. “Look at how much stuff you all dragged out!” our mother yells. “This better all get put away!” Before we are teenagers, we have just two “rock” records at our house, Jesus Christ Superstar and Hair, purchased by our parents in a futile effort to keep up with popular culture. Superstar is okay, if a little close to Sunday School, but on Hair you can fly clear out of the county. We spend hours doing just that, all six of us flinging our bodies round and round the dining room table, barely conscious of each other, spellbound by our spectacular dance moves. We’ve memorized every word whether we understand it or not and wail, “Sah-duh-MEEEEEE. Fuh-lay-shee-OOOOOHH. Cunni-LIN-gus. Peder-ASTY,” while in the next room our mother, in her perpetual state of seething duty, cooks dried-out deer meat and canned vegetables for eight. Sam and Laura, the only feminine female in the family, don tablecloths and stand on chairs so they can watch themselves in the mirror. One arm wrapped around the waist of the other, torsos swaying, Laura’s head not reaching Sam’s shoulder, they croon “Frank Mills” into Ping-Pong paddle microphones.

Our parents don’t divide chores by gender, with one exception: It’s Sam’s job to dispose of dead animals the dogs drag in. Otherwise, we both load the hopper for the coal furnace; we both run the vacuum cleaner; we both cut grass; we both clear the table; we both work the garden. So outside the family, I’m always surprised, then embarrassed, and finally mad when people separate us into boy work and girl work. Because our father is a part-time minister, all eight of us are regularly invited to oven-fried chicken dinners at the homes of old ladies with reverend crushes. After we arrive, the old lady will press us three girls into kitchen service, and while we fold napkins, fill water glasses, haul platters to the dining room, I shoot dirty looks at Sam, who gloats from the couch. Before we are old enough to work legally, he and I earn under minimum at a packing shed, me on the line with the other women and one old man with a bad leg, weighing, bagging, and binding apples, then placing the plastic bags on a long table behind us, where Sam piles them in partitioned boxes and stacks them. It’s the most boring work I’ll ever do. Once, after a morning and half an afternoon, I ask Sam if he wants to trade, and we work that way for another hour, me relishing the heft of the boxes, the good push-back in the muscles in my arms, the understanding that at least I’m using my body if not my mind. Until the boss walks in and immediately orders me back to the bagging line.

But although work at home is androgynous, fun is a different matter. In small town West Virginia, the three most valued activities are church, hunting, and sports, in that order. As a girl, I’m barred from two. Sam is obligated to all three. For years I watch our father march him off with his .22, then his .30-30, Sam’s ears scarlet with revulsion, while I pine behind, livid with injustice because I love the woods ten times more than Sam does, and disgusted that women’s rituals-canning, sewing, quilting, cooking-are all work and all indoors. Our county doesn’t have a girls’ sport until Girls Athletic Association basketball in 7th grade, and by then, I’m too self-conscious to put myself on a court. Before that, when I’m still yearning, I sit tensed in the bleachers while Sam flounders through Biddy Buddy basketball, his flailing arms, his dark cloud of hair. I watch him stumble bespectacled around Little League right field, the only kid with a blue glove. At home, I borrow the glove to play searing games of catch with Catherine, and when she and I tire of that, we face off in impassioned one-on-ones, dribbling, guarding, swatting, stealing, all without a hoop. I run as fast as I can through the pasture, the cold burn livening my lungs, then veer up onto the deer paths strung along the mountainside. I forget myself in balance and speed and leaps over logs.

OUR FATHER HEARS IT ON WELD. The strike is still on. Another week of no school. The only thing worse than going, I know by this time, is staying home. Sam’s in his room, spiraling his tornadoes and worshipping his Hollywood books. I’m in mine penning furtive sketches of the boy I’m in love with and laboring, without success, to draw the stories I hear in my head. We have been banished to our rooms for…fighting each other? Picking at the little kids? Teasing Laura, excluding Catherine, flicking Michael in the head? Despite the circumstances, Sam and I are always guilty, because no matter how young we are, we’re still the oldest.

I roll off my bed, stand over the trash can, and rip my sketch into a thousand dirty snowflakes. I pace from window to window to window, then stop in my doorway, lap each foot halfway over the threshold, mentally daring my mother to storm up the stairs and catch me. But whatever it is we’ve done, I know that even if we acted out of rage, out of what I have no other word for but hate, I know this, too: Sam and I stay away from faces. We never bloody lips. We rarely pull hair. We don’t physically fight the three youngest kids at all, and our fighting each other and Catherine is mostly a ferocious and infuriate wrestling with punches to biceps and struggles to throw each other down. Only the little kids bite, and we pinch with fingers, never with nails, this rule we even say aloud. I know what happens when you kick a boy between the legs, I’ve resorted to it several times at school. It never occurs to me to use it on Sam.

So when I, and I assume, Sam, fight family, we fight always from a not quite conscious restraint, in the frustration of the always-hold-back. We get only the short-lived release of fist meeting undamageable muscles, the half-catharsis of pinning the other one down. And what is it that holds us back? Responsibility? A preservation instinct toward shared genes? Fear? Love? Regardless, we have no unfettered outlet except tears and self-hurt, me punching one palm with my other fist, banging my head against the wall.

I press my body against my bedroom window, savor the cold from my belly button up. One dog jogs along the edge of the yard, her mouth flopped open in happiness. I grind my forehead into the condensation on the pane and listen to my younger siblings downstairs chasing each other, laughing. I’ve already asked three times if I can come out, and I hear Sam call the same and my mother yap, “No!” I feel my mind lift out of my head, I feel it rising. I feel it grating against my stained ceiling, I feel it force and squeeze and press. I feel it bust into the attic where my father says blacksnakes live, I watch it thread those snakes, hear it butt the underside of the roof. Soft thuds. Good hurt. The fourth time I call, “Can I come out?” my mother groans, “Yeess.”

I make a face at her she cannot see, grab my hat, gloves, and boots, and hammer down the steps.

ON THE ICE, THE DOGS RANGE OUT ahead of me, vanish into duckweed, corn stubble, multiflora rose, check back in. At my heels pads a yellow cat named Mr. Paul who, having lived only with dogs since kittenhood, doesn’t know he’s a cat, much less that cats don’t trail humans for hours. The ice reveals to Mr. Paul and me secret places, places I can never reach during a regular winter when the river, if it freezes at all, doesn’t freeze this solid and never this long, places I’ve never explored despite their being less than a half mile from my backyard. Frozen lagoons carry us into bough-arched coves on the river’s far side, and I can prowl the banks where summer would never let me with its thickness of brush, the itchweed and snakes. We’re given passage to islands I’ve seen all my life and my father has names for, but that I have never been able to reach, and on one of these islands, I discover the abutments of a century-old bridge, softened in grapevine and leafless poison ivy. Elsewhere, crumbles of smaller buildings, skeletons of rodents and deer, a washed-up johnboat half eaten by a mound of silt. Mr. Paul patient beside me. The good give of my grandfather’s boots.

I’m exquisitely warm except where my face meets air, and that sear-your-cheeks cold is exquisite, too. I move in the counterpoint between the sound of my breath and the sound of my soles, on solid ice, on honeycombed ice, on the stray patch of old snow. In the middle of that river, me moving in the open treeless flat, I’m not thirteen. I’m not the mean older sister, the shy junior high student, the weird smart girl. Time softens, and in this place and this moving, I am exactly who I was playing in the creek at age four, exactly who I will be thirty years from now along some Northwest alpine lake. I am in step with everything else, I feel it, the rhythm of what beats behind. Even though to the ear nothing sounds except breath and ice, to the eye nothing moves but clouds and dogs, cat and me.

One dog skitters back, scramble-pawing the surface. I pull off my glove, take the hot nose in my hand. I lift my face and see the moon in the day sky like a boot heel track on waterlogged ice.

IN FIFTH GRADE, A NEW KID APPEARS in our class. At first, no one can tell if it’s a boy or a girl. His soft neat brown hair curls just over his collar, and he wears plaid pants. Both his half-smile and his huge eyes quiver like match flames, delicate and incapable of shielding themselves. I like Kevin Stephens very much. One Monday morning, Kevin shows up with all that soft hair shaved to the scalp.

Some kids tease him about it, but when I ask him at recess what happened, I am honestly confused and a little concerned. His dark eyes glisten under the stripped skull. “My dad did it so I’ll look like a boy.”

Our father never pulls anything like that. I never see him punish Sam for his effeminacy or deride him. Not for the pre-schooler drag, the athletic fiascos, the jumping out of trees with umbrellas in Mary Poppins impressions. Not when the Women’s Club dresses him as Minnie Pearl for their Hee Haw fundraiser-and Sam doesn’t mind it-not when he and Laura roller-skate to Donna Summer albums on the concrete slab out back. Our father deals with the aberration that is Sam by removing himself from it.

Our father deals with all of us this way to some extent, and it’s a method I much prefer over our mother’s relentless surveillance and hotheaded “discipline.” In truth, she’s the only parent who directly comments on Sam’s difference: “Stop that prissing around!” But our father stays more remote from Sam than he does from any of us others. And this aloofness sinks a barb into each of Sam’s cells.

When I am young, I don’t understand. Sam rails nonstop about how much he hates our father. Then why does he still crave his attention, want intimacy? I also don’t understand why he can’t just see how our father is. Because although this is not something I know in a way I can say, not even in my head, I recognized at a very early age our father’s fragility. His self-absorption and remoteness and passivity are in part, I understand, the fallout of a dark sensitivity that nearly disables him. I hear this when he tries to yell at us and can’t manage anything louder than a desperate whine, watch it in his defenselessness when our mother yells at him, in how the only thing he ever asks for for Christmas is “a little peace and quiet.” Most nakedly I see it in the way his eyes look without his glasses. I witness this rarely, usually only when I wake him from one of his naps, but when I do see it-the short reddish lashes, the small wet blue eyes, his face completely unprotected-his vulnerability is so exposed I have to turn away.

I know he is simply unable to behave like a “regular” father, and for the most part I accept this, like I accept his bad back, which means he can’t play running games or pull us in a wagon. But there is this, too: It is through my father that I have learned the refuge of woods. Have learned it by watching him disappear into them alone, but have learned it also through the many times he has taken me with him. Yes, while my father disappoints me and often angers me, he’s also given me the outdoors, and because I expect so little else, I have little to forgive.

But I am not a son.

When Sam is six and then eight, our youngest brothers are born, and with their arrival, our father’s detachment from him is finalized. Because “the little boys,” as we call them well into their twenties, are real boys at last, who love football and guns and Tonka trucks and chopping down trees, much as Laura, born right before them, likes dolls and dresses and arranging hair. The three youngest fit their boy-ness and girl-ness exactly as they should, as though my parents bumbled along procreating for six years before they finally made gender right. And the love and attention the younger children seem to receive, which we do not, always feels, rightly or not, tied to the way they match up with what they’re supposed to be.

BY THE WINTER I’M THIRTEEN, even I understand that the charge I feel around Sam’s difference, my aversion to it, my shame when it’s mentioned, is out of proportion to the usual embarrassment one feels for a sibling’s oddities. Even that early, I sense murkily that something else is at stake. If I shovel deep enough and am then brave enough to look for more than a second at what I turn up, I know this: Sam’s being more girl than me also means I’m more boy than him. My brother’s “woman-ness” puts into sharper relief the lack in me.

I’ve recognized I’m not your usual girl since at least kindergarten, and it becomes more distressing as the fork between “boys” and “girls” widens with each successive year, climaxing in the eighth grade. Makeup confuses me, nail painting I find absurd, and I’m only drawn to jewelry like the leather bracelets we engrave with names during 4-H camp craft time. I never feel totally safe in a dress. In grade school, my mother and I compromise and I wear one just three days a week, but on tights I will not yield and instead yank on mismatched white kneesocks, even in temperatures in the twenties and teens. By junior high, clothes bewilder me and hair I regard as something you comb in the morning then hope for the best. All this worries my feminine friends who tamper with my sweaters and shirts and belt at lunch, and experiment with my hair at slumber parties.

I do compensate for my less-girl tendencies in small ways that don’t make me a complete traitor to myself, like reminding myself not to sit with my ankle on my knee. I carry my books against my chest when I think of it instead of dangling them naturally at my side, and I know never to wear my grandfather’s boots to school. It’s not that I feel like a boy. I don’t. But I don’t feel like a girl, either. I just feel like myself.

For the most part, I accept my deficiencies with a muted, what-can you-do-about-it regret, not unlike the way I accept my father’s inability to be a normal dad. Besides, even in my state of diminished girl-ness, there is no shortage of boys interested in me, even if they are almost never the ones I’m interested in. The culture in which we grow up grants far more leeway for expressing oneself as a woman than it does for expressing oneself as a man, and while at first thought this seems strange given the sexism of the place, on second, it makes sense: If everything male is superior, why wouldn’t a masculine woman be more acceptable than a feminine man? Catherine is a bigger tomboy than I am, but no one ever asks me questions about her. We grow up with loads of kick-your-ass women stomping around, I-can-run-a-chainsaw-AND-nurse-a-baby types, almost all of them married or once married to men.

Not until junior high do I really grasp what “gay” is. I learn about “queers” through rumors about Mr. Simon, the mysterious tight-panted eighth-grade math teacher, condescending and fox faced, who came from someplace else. None of our female teachers appear to be gay, and “lezzies” are discussed less frequently. And because I’m obsessed with boys in general and madly in love with one in particular, that I might be a lezzy is not one of my myriad anxieties.

My mother’s not much of a coach on young womanhood, which, as far as I’m concerned, makes her more of a blessing than a curse for a change. Other girls’ mothers teach them how to apply eyeshadow and some even seem to siphon a thrill off their daughters’ adolescent romances. To my mother, my gender is only pregnancy potential, and she lectures me about this incessantly in brusque, veiled language. The only other measure she takes is to order me to wear a bra.

Since fifth grade I have observed with cold dread bra straps appearing under other girls’ shirts. My mother doesn’t mention “bra” to me until seventh grade, and by that time, my breasts are peculiarly sore, but no bigger than an unspayed beagle’s. No one can tell if I’m wearing a bra, I decide, unless I’m in a nearly transparent T-shirt. So I don’t wear one whenever I think I can get away with it.

I’m in one of my favorite shirts, flannel, with just a few girl flairs-a billowiness, buttons only halfway down-to rescue it from full-fledged boy clothing, on the day the vice-principal surprise announces the scoliosis check. I march off with the other eighth and ninth-grade girls, happy to get out of class. Until we’re ordered to remove our shirts and stand in a long line in our bras and jeans. For a second, I think I’ll throw up. I immediately invent a lie, beckoning the vice-principal and confiding in her that my mother doesn’t want me to have this examination. I’ve already had one. My mother said I don’t need another. Mrs. Kelley smiles, tells me it won’t hurt, and ushers me back into line.

Most of the girls hunch over, shielding their bras and giggling. A few of the breast-brazen stand erect and defiant. I huddle humiliated, my arms crossed over my almost flat chest, the only bra-less girl in the eighth and ninth grade.

This does not go unnoticed. Later that afternoon, while we’re changing classes, the boy I’m in love with corners me on the blacktop. ”Are you wearing a bra?” The tone is punitive. Not sexual. Not even curious.

“Usually I do,” I say.

“Well, you better,” he says. He turns and jogs away.

ONE FROZEN INTERMINABLE SUNDAY THAT WINTER, our father rises from his afternoon nap and announces he’s taking us kids on a walk up the river. Often on Sunday afternoons, he’ll do something like this, climb out of his detachment and usher us on outings. Our mother, famished for alone time, never comes along. On these outings, which began as soon as I could walk well, my father has taught us the names of trees and tracks, of hollows, ridges, and river eddies. More important, but without speaking of this other, he’s showed me how to be with those things he names. How to look at them and behind them. How to hear the silent vibration that drums through and between them, as palpable as my own heart pushing blood.

Today, the solace of outside is muddied by my mortification of being seen with my family, whom I know, in their dishevelment, eccentricity, and sheer numbers, are even worse than the families of most teenagers. I decide I’ll accompany them until we get to the river, then take off on my own in the opposite direction. But when we reach the ice, I find myself turning upstream with them because, I tell myself, there won’t be a soul on the river to witness my presence in this pathetic entourage. And, I don’t tell myself directly, because I can only think it under words: time with my father, even diluted by five other beings, is precious.

I keep to the outskirts, range twenty to thirty yards off the perimeter of the group. Sam orbits the outside, too, but closer in, him like Mr. Paul, me like a dog. Ahead of us, the four little kids bubble around the pole of my father, them in their motley hand-me-downs, their hoods and tied-on hats with tails, the brown cotton gloves with cowboys on the backs worn by all the little kids in town because Santa hands them out at the bank party. Sam and I are dressed almost exactly alike, each of us in a plaid wool coat we got for Christmas, identical in cut, different only in pattern and color. Our boots are nearly the same, too, only Sam, because he’s a boy, gets a new pair at Western Auto each year. Sam is in the kind of knit cap we call a toboggan, forest-green with a maroon stripe around the brim. I wear a Miami Dolphins toboggan not because I’m a fan, but because it’s the only team our town’s clothing store had on the rack.

We move in our disjointed troop over the ice, under a sun dampened by rumpled clouds, between the skeleton-work of naked trees on the banks. Once in a while, a little kid will kneel, drop their face to the surface, and try to see through. When we reach the giant sycamore where we usually turn around, we take a break. The younger ones run and slide in their rubber boots on the rumpled, pitty ice, ice-skate-pretending. I turn my back on them and climb the steep bank to the cornfield above us.

Up here, on the side of the river opposite our house, the fields hold the mountains back a little. I can squint across more than a mile of broad bottom, spot the dogs in the stubble snorting groundhogs and rabbits. This valley is the biggest open I ever enter, and I can reach it alone only by swimming or by way of the ice. It’s even colder up here, with more wind than on the river, and I pull my chin into the collar of my coat. In this wide open, there spreads out of me a yearning, without shape and with nothing touchable at its end. Up here, there is no place for it to stop against, like there is in closer-in mountains, like there is on the frozen river, a more narrow open than this up here. I stand with this widening feeling until it’s just about to frighten me. Then, quick, I turn away and scrabble down the bank to a ledge not far above the ice.

And jump.

My boots slip when I hit the ice. I pitch forward, and one hundred ten pounds crash onto one knee. At first the knee doesn’t understand, then the pain missiles in, ricochets through my whole right side, and missiles back to the knee. I’m collapsed on my hands and the unhurt knee, and before I can stop her, the child in me swim-kicks straight to my surface, open-mouthed desperate for sympathy. And hears Sam burst into laughter.

I jerk my head, and through my dangling hair I spy Sam pointing at me so the others can see how funny it is, too. I surge to my feet to go after him, the knee shrieks, the tread less boot slips, and I fall back on my hands on the ice. Then I remember our father’s here. And he hasn’t laughed. But he also hasn’t said a word of comfort or of reprimand.

“Why don’t you do something?” I scream. “I hurt myself, and he’s laughing at me.”

My father doesn’t look at me. As I sprawl on the ice gasping with rage and injustice and hurt, he herds the younger children together. I tug at my pants leg to show the damaged knee, but the denim’s too tight, and now the others are floating away. Anger tears, the only ones I ever make because they’re the only ones I can’t control, heat my lashes, my cheeks, and my anger at those tears makes even more. I finally hoist myself to my feet, still clutching the knee, my hair wild in my face. Watch the ice expanding between my family’s bedraggled backs and me. As usual, Sam follows a little ways off and behind. He turns for a moment and smirks at me.

THE TRUTH IS, WHEN WE WERE IN GRADE SCHOOL, I spent almost every Friday night in Sam’s room. On his top bunk until the bunk beds were given to the little boys, then on a pallet of blankets I’d heap on his floor. The truth is, even though I was fearless outdoors, I was terrified of indoors dark. When I slept alone it was always with covers over my head, and more times than I wanted to admit I was reduced to bleating for my mother who would shuffle, exhausted, into my room, murmur that I was all right, then shuffle away. She wouldn’t let me sleep in Sam’s room on a school night because we talked too much. On Friday nights, if I’d been good, I could.

And we did talk, about school, about movies and TV, he listened patiently while I rambled on about my classmates. We turned the way our parents injured us into jokes, we invented codes, intoned, “Sweets for the sweet, macaroon” as our secret phrase for our mother’s ability to don a saccharine public face seconds after verbally flaying us. As Sam and I lay invisible to each other, the fights had never been, would never be. With our bodies vanished, our spirits touched. Twin outsiders, conjoined scapegoats. Solitary together.

By grade school, Sam sleeps silent and still, even through mysterious nosebleeds that wash his pillow red. But when he was a toddler, he was a headbanger, and right after that, a bedrocker. I can’t remember why I slept in his top bunk then, I didn’t ask to, but I was often put there. In those times, when we were three, four, five years old, I’d lie in that top bunk, swaying, and let Sam rock us both to sleep.

I CONSTELLATE AT A DISTANCE. The pain-pulse in my knee is the perfect background beat for my righteous indignation. My lips are parted, my teeth bared, the ache of intense cold against them both provocation and perverse comfort. I feel the hackle of my shoulders, my arms forked off my sides. I am cocked. I move in that aural paradox of frozen dry air, the way it mutes background hum yet amplifies each individual sound, me steal thing along in the hah of my breath, the snuff of my running nose, the shatter of my grandfather’s boots on brittle surface ice. No one in the family looks back at me after that one Sam smirk. My father like a stake with the four younger ones tethered off it.

As I draw nearer, I step carefully around the crusty places. I let my nose drip. Sam is about forty feet off to the side of the others.

I rush him from behind.

He yelps as I knock him down, his voice immediately muffled by his scarf and then my body. I’m on his back punching him through his plaid coat, kneeing him in the butt. He twists out from under me, my toboggan-padded head thumps the river, we grapple on our sides to keep each other down, our bodies spinning together across ice, no purchase for feet, for elbows or hips. My bad knee slams the ice and I suck air at the shock. Until the year before this one, I was always a little bigger, a little more powerful. Now at twelve and thirteen, we’re exactly matched. I snake one hand up his sleeve, the surprise of the warmth even through my glove, and clutching him by that bare arm, I make a fist with my other hand and pound his coat-covered ribs while he grabs my face with his spread palm. But I shake free. Then Sam rips loose, screams some insult, and darts away, slipping and catching himself, adjusting his glasses as he goes. I’m left slumped on the ice, heaving for breath, hot enough to melt a hole.

He trots after the family, all of them currenting slow down the river under the dimming sky. I see one of the little boys point off to the side at something, and they all look. No one looks at me. I roll to a squat, and then I hunch there, a human bonfire of hatred. The kind of hatred one only feels for family, that very hottest hatred because of how much else is in it-the history, the allegiance, the jealousy, the way they look and smell like you, the play and work and make-believe, the love. How all of that, instead of diluting the hatred, concentrates and magnifies it, as though the complicatedness opens up crevices and shafts and craters inside, giving the hate more places to penetrate. Yet despite that, and because of that, even now I fight him with maddening restraint, with half-powered punches, under frenzied self-control not to really hurt, fury screaming against responsibility. I stagger to my feet, not even feeling the knee anymore. Nothing in me any longer thinks. I am animal and I am ancient, hypnotized by the heartbeat in my ears. This time, I don’t even walk. I hover over ice. The last stretch I sprint without touching down.

I slip right as I reach him but pull him down with me anyway, then we’re thrashing on ice, and I taste, familiar, his bare fingers in my mouth. I hear his glasses skitter away, he seizes the ends of my scarf to choke, I recognize a great idea and do the same. The cotton burns my neck like carpet on a bare knee, Sam gnashing a steady stream of hate words while I can manage, as always, only hisses and grunts, and he finally pins me under him, still sawing the scarf, the spit from his names spattering my eyes, and then he pivots into a position from where he can both hold me down and kick, his boot hammering my shoulder, me so adrenalined I feel only dull thuds. Then I seize his kicking leg, and he topples so hard I hear a crack way down in the ice. And behind all this, a vague awareness that our father knows, may even be watching. But does not intervene.

The next time it is Sam who attacks. I see him coming, I brace, I meet him chest to chest. From then on, we ambush each other by turns, ripping off toboggans and sailing them away, grabbing arms to reel the other down, at least once me riding his back, him knocking me loose by dropping and rolling. Then we retreat, panting like boxers, him scurrying to the edge of the others, me taking refuge in the aloneness of the ice. The other kids glance our way occasionally, but they’ve seen us fight a hundred times, and lose interest fast. If our father were asked why he doesn’t step in, I know in the dark of my brain what he’d say: I’m just sick of your all’s fighting. And I don’t have the energy to fool with it today. In a thin pinched voice while his eyes roam away.

By the time we reach the old grape arbor that runs the length of our backyard, I am so wrung out I can barely stand. We must all pass the arbor to get to the house, its grapes long dead from blight, the wooden trellis still supported by cement posts the girth of my thigh. I’m of course in the rear, Sam a bit in front of me, one wary eye over his shoulder, my father and the little boys just ahead of Sam. I see Laura and Catherine racing ahead, I hear the screen, I know the fight will be over the second my mother finds out. I inhale, and in that swell of lung, I gather every particle of power I have left. I harden my face, my teeth, my hands. I barrel across the yard and fling myself at Sam.

We have each other by wads of coatsleeves, each of us bent-kneed and panting, desperately trying to swing the other down. My eyes blur with exhaustion, it’s only colors and textures I see-the over bright green of the frost-sharp grass, the gray-blue quilting of sky, the already dark mountains leaning all around-and I cannot think at all. We are too tired even to punch. He tears off my toboggan and I rip away his. We stagger there, deadlocked in our embrace, until I hear our father say, in a voice unloud and without emotion, as though he’s offering mundane advice:

“Hit her head against the post.”

At these words, some last reserve volcanoes into Sam. I feel it before he moves. Then he shoves me, hard. My body finally fails. He slings me across the short span of yard between us and the arbor. He slams my head into the cement post.

I feel first just raw scrape of scalp, then a ring-more light and sound than hurt-until it ripples out. The agony hits in the echo of it. I drop on my side, blinded, and inside my skull, a hard black wave batters side to side. I don’t pass out, and I feel nothing-no anger, no self-pity, no righteous indignation, no vengeance, not even hate-except my struck head.

Then I’m on my hands and knees, crawling away from the arbor across hard grass to retrieve my hat. I half-see, half-sense Sam and my father-I register the anomaly of the two of them together-almost to the door. I hear my father say, “She won’t be fighting you again.”

EVEN NOW, THIRTY-FIVE YEARS LATER, I feel more surprise about his telling Sam to do it than I register injustice or brutality. Simple surprise because our father-passive, self-contained-had never before so explicitly stepped in. I’m not surprised once he got involved, he took the boy’s side-even if that boy was one he held at a distance all his life-because convention deemed it “natural” that he would. “Natural,” too, the roles he assigned us: conquering male, victimized female. I am not surprised he broke the subtle rules of our fights, our code of restraint, of responsibility for each other, because his all-or-nothing perspective seemed to me the way grownups “naturally” thought.

But perhaps the unfairness and brutality don’t faze me because the “natural” order of things was exactly what Sam and I had already learned to give the slip. I don’t remember in detail what happened after I went down, but obviously I picked myself up, no doubt sought comfort from the dogs, and after some time feeling sorry for myself, returned to being me. In the end, the boy slot and girl slot our father slammed each of us into held not much longer than the ringing in my head. Even if we weren’t aware of it at the time, Sam and I had started the process of making ourselves our own kind of boy, our own kind of girl.

TWO WEEKS AFTER, the temperature spikes. The river breaks. I hear it in the night. Table-big slabs of ice wreck up along the banks, and the secret places on the islands and the far side are once again shut away.

I climb over the stranded ice chunks with my coat hanging open, no gloves, no hat. My boots are mud to their laces. Thaw smell richens my head, the softening soil, the rotted plants, the fecund dead. In the ice I discover barrels that used to be docks, a hellgrammite seine, a woman’s plastic raincoat, the corpse of a great blue heron, all of these surprises, along with the aroma of spring, the river’s compensation for binding me again to one bank. I range over and under the puzzle of sycamore root, balance on exposed rocks, relish the hold of boot leather below my calves. The dogs are intoxicated, too, but the ice is too sharp, the ground too mucky, for Mr. Paul. He labors behind me for a little while, and then he vanishes home.

Back at the house, the little boys ride their Big Wheels. Our father takes a nap. Our mother stirs the chili. Catherine pounds a basketball. Laura comforts a doll. The blacksnakes prowl the attic. Sam pores through his movie star books, creates a fresh tornado.

I don’t know that in just ten years, Sam will move to Los Angeles, step into his books and eventually onto the screen, a place and a profession where he can be any kind of man he chooses. I don’t know that I’ll be less certain, live in ten different places in my twenties and thirties, love both men and women. I don’t know that many women in other regions are more choked than women in Appalachia, but if I skirt the prevailing current, there are ways to be a woman never imagined back home.

What I know, along this thawing river on top of muddy ice, is how to stand still enough long enough that the front of my chest falls completely away. How to feel dogs, water, sky, trees, beating in time with what moves behind. How it’s only when I find that rhythm in myself that I reach my realest me.